Editorial

From time to time in every line of work critical opportunities arise, vantage points from which crucial decisions can be made that will fundamentally reshape the character of the sector. Although many minds are properly focused on crisis management at the moment, part of any enduring solution includes regular management as well, maintaining perspective and attending to opportunities that are not crises and where immediate decisions are not required. These non-urgent matters of import include decision opportunities such as capital replacements where major improvements can be set into motion, even though no alarm bells are going off. A little foresight along with prudent action can have great payoffs down the road, and considering the circumstances, may be a welcome compliment to the fire-fighting and emergency mindsets, necessary as they are at the moment.

Ontario’s current position in terms of long term electric power resource adequacy is one of these slow-moving opportunities. There is no shortage of electric energy at the moment. Only minor needs for capacity are anticipated in the near future. However this doesn’t mean everything is fine. There are major uncertainties and an abundance of indicators warning that change is the new normal. The IESO has announced that its planned Capacity Auction is being postponed for a few months, along with the stakeholder engagement related to it. This may have implications for the related set of consultations on Resource Adequacy and Alternative Procurement Mechanisms which were also being re-thought and which were expected to restart shortly. At some point before long a new framework and schedule will need to be released. Major stakes are on the table. It’s a propitious opportunity.

Planning has become more difficult but remains every bit as essential as before. Our readiness to deal with systemic change could be more important than how well we plan for what we already know.

Ontario’s overlooked planning problem: the danger of losing existing capacity

Ontario’s Annual Planning Outlook, released in January, is the subject of much analysis and discussion, as it should be. It is the most important baseline for planning all manner of investments related to the power sector in Ontario, both public and private, short term and long term, customer-owned and utility-owned.

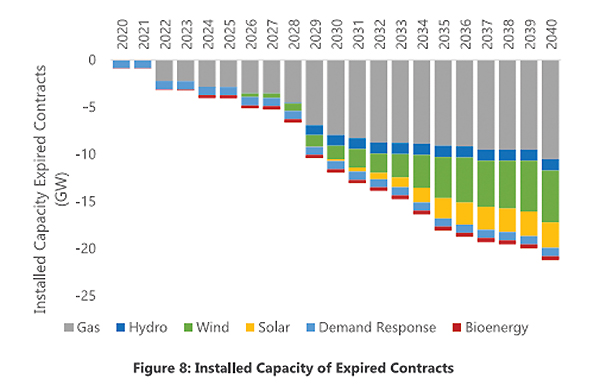

Well before recognizing the need to recalibrate the Planning Outlook in response to COVID-19, a number of analysts observed that the Planning Outlook raises some interesting and problematic questions. In one critical area for example, it assumes existing generation capacity will continue into the 2030’s, even though most IPP contracts will have expired long before that time, and virtually all the generating plants will need capital investments if they are to keep producing during the period foreseen by the Outlook. This uncertainty is understood by the IESO and forms part of the plans for its engagement on Resource Adequacy. It sees 10,000 MW of existing capacity coming off contract by 2030 and twice that much by 2040. (See chart.)

Graphic courtesy of Power Advisory LLC, based on data from the IESO APO 2020 data modules.

Quite simply, if no action is taken to retain this capacity for the longer term, the anticipated level of supply will not be available and the province will likely find itself scrambling to meet demand, at least for parts of the decade ahead. The IESO’s new proposed Capacity Auction may help to a certain degree. However it’s going after short term capacity at a minimum cost, and the amount available under these terms remains to be seen. No one can say at this point whether the revenue streams from that auction will be sufficient to keep existing capacity in place. Further, there are serious doubts that it will be sufficient to attract all the necessary types of supply in the required amounts and places.

Graphic courtesy of Power Advisory LLC, based on data from the IESO APO 2020 data modules.

Quite simply, if no action is taken to retain this capacity for the longer term, the anticipated level of supply will not be available and the province will likely find itself scrambling to meet demand, at least for parts of the decade ahead. The IESO’s new proposed Capacity Auction may help to a certain degree. However it’s going after short term capacity at a minimum cost, and the amount available under these terms remains to be seen. No one can say at this point whether the revenue streams from that auction will be sufficient to keep existing capacity in place. Further, there are serious doubts that it will be sufficient to attract all the necessary types of supply in the required amounts and places.

A number of APPrO members have warned that some of their older plants, particularly gas-fired generation facilities, will start to break down or be forced to operate at reduced levels, unless significant funds are invested in long-term maintenance, otherwise known as capital expenditures. For those companies facing Capex requirements, there will be a simple calculation to make: Is the assured level of revenue from the Ontario market over the capex financing period, usually 5 to 20 years, going to be greater or less than the cost of the capital expenditures? If the answer is less, then that production is clearly in jeopardy. If that hurdle is passed, the investor must ask an even tougher question: Will the return on capital be sufficient to warrant investment relative to opportunities in other jurisdictions? If other uses for capital are more attractive, the investment will not likely materialize. This risk is not represented in the Planning Outlook – the capacity is assumed to be continually available.

There are other uncertainties in the Planning Outlook. Any one of a number of changes could lead to more or less supply being required. Electric vehicles and electrified public transit could take off. Customer-owned, behind the meter, and distributed energy resources could expand. Considering how difficult it is to get large new transmission facilities built, bulk transfer and reliability issues could crop up in certain areas even if total provincial supply is adequate.

Ontario is in the early stages of building a new planning framework. Will it work for managing the uncertain and exacting demands of the future power system? Is it ready for the next disruption? Experts tell us that the APO is less rigorous and less complete than the analogous plans for some of the comparable jurisdictions. The outcomes from the IESO’s consultation process and the updates to the Planning Outlook are where the true story, revealing indications of what actions are needed, will be told.

It’s time to get crackin’: Market sensitive solutions have to be timely

The Ontario government, the IESO, regulators and most market participants agree on two things: The options chosen for meeting future supply needs must be efficient and based on consumer demands. The best way to ensure these standards are met is by relying on competition, making sure that new capacity, and even the continuation of existing capacity, is rewarded through market-based revenue streams, to the maximum extent possible.

One of the first debates that will arise is the extent to which the proposed new Capacity Auction, as conceived in Ontario, is actually a market based revenue stream. Or is it essentially just another centrally administered procurement program?

While there is no hard and fast line between the two categories, some key indicators that a process is truly competitive and market based are:

a) Is participation voluntary?

b) Is there a diversity of players vying to compete?

c) Do prices respond quickly and efficiently to changes in real world conditions?

d) Is there a truly open and level playing field, with no entities having market power that can’t be mitigated?

e) When price trends become apparent, do they converge with prices discovered in other competitive processes?

The great danger here is that Ontario may fritter away years tweaking the design of its Capacity Auction while other opportunities to secure reasonably priced reliable supply may be lost. In a process affecting billions of dollars in annual costs to the public, this kind of risk must be monitored and managed actively.

The IESO of course appreciates all this and has responded in part with a proposal to engage stakeholders in what’s generally referred to as “Alternative Procurement Mechanisms” or APM.

The problem is, we’re still at square one, not even out of the starting blocks, on APM. There’s no timeline for resolving the framework of the discussion, nor any concrete outcome required by any certain date. In such a situation, the same risk remains: opportunities to benefit ratepayers could be forfeited, leaving the system with fewer options at a crucial point in the future when it may need to secure capacity in a rush. No one knows if that scenario will develop but the risk is serious enough that contingencies are required for it in any comprehensive plan.

The IESO has been saying for years that there is likely to be a capacity shortfall starting in the summer of 2023. Although forecasts will certainly need to be adjusted in the wake of COVID-19, power demand may have bounced back in 3 years from now. The IESO is sensibly looking for inexpensive and fast options for meeting capacity requirements that can be fully operational in a little more than three years from now. Currently the two most widely available forms of capacity that can be lined up quickly in most locations are gas fired generation and battery storage. (Demand response and imports may also be available quickly, but there are more restrictive physical limits on their amounts and locations.) These technologies have very different prices, cost structures, and risks. Whatever procurement procedures are set up, they will likely need to be functional for gas-fired and battery-powered types of resources. It will be interesting, not to mention useful, for consumers to see the result of open competition between different types of generation and storage to meet these capacity requirements. May the best capacity win!

A well-scoped RA process will minimize capital costs

As Ontario takes steps to secure the right kind of capacity, the central challenge is formidable: How to ensure we maintain reliability without paying too much, during a period of change. It follows that planners need to maintain flexibility and keep options open to secure capacity.

There are several moving parts to keep in mind:

1. Flexibility: You want to keep a range of viable supply options open, without committing large dollars in the early stages.

2. Stability for the purpose of capital cost minimization: Ensuring that contract holders have an adequate line of sight prior to contract expiry is a significant part of keeping lower cost options on the table. This needs to be better understood in planning and in public debates. The better line of sight existing operators have, the more low-cost options they can offer ratepayers and the grid operator. Having longer-term revenue streams in the mix will likely result in more investment.

3. Keeping multiple procurement tools available: This means making sure the central agencies and other buyers have sufficient ability to try almost anything that could be viable. For example, recommitting to existing capacity, using new Resource Adequacy mechanisms, making refinements to the Planning Outlook, implementing Alternative Procurement Mechanisms, and developing additional tools, while respecting whatever insights emerge from the contract review process.

4. Laddering: It’s prudent to make some level of commitment for each future time frame. The longer you leave making a decision for each time frame, the fewer options you have left, and the more upward pressure there will be on price. You don’t want to make too many commitments at once, but neither does it serve the cause to make zero commitments in any given time frame.

Keep making sense

Ensuring grid adequacy is a little like building a loan portfolio at a bank. You need to have a basic plan in addition to a hedging strategy for each time frame. Then, you need to re-evaluate the plan for each time frame systematically. This is not the same as cherry-picking whatever is most convenient at the moment - although it should probably include a fair helping of cherries when convenient.

Even before the recent disruptions there was a significant weakness in Ontario’s resource plan, and signs that more could come to light.

With this in mind, as one of the tools in its arsenal, the IESO should consider developing a procurement process, in consultation with stakeholders, to re-contract capacity from suppliers who are approaching end of contract. This category of resource will generally be low-cost, readily available capacity in the places where Ontario needs it. It repairs a weakness in the Annual Planning Outlook that assumes the capacity is actually there throughout the remainder of the 2020’s when in fact no mechanism exists to retain this “existing” capacity. This kind of renewed capacity can be market-sensitive and customer-responsive in ways that are distinct from many of the alternative procurement options. Some observers are warning that the current framework which only includes one-year capacity commitments does not provide sufficient certainty to suppliers to make the investments necessary to maintain reliability. Multi-year commitments, a sensible idea that the IESO is already working on, will help to fill this bill.

A procurement process designed to attract capacity from existing suppliers need not be closed to other resource types. The competitive process, wherever possible, should be an all source process with no specific set-asides with respect to generation type, and should be open to demand side resources as well.

Consumers, producers and the grid operator have a shared objective here: to define a procurement process that’s market sensitive and suited to Ontario’s needs.

This is the time to get it right, to put a properly scoped resource adequacy process into motion, even though no alarm bells are going off.

— Jake Brooks, Editor