Clearly defining the roles of local distributors in developing and managing Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) is not an academic question that can be left for a later point in history. Achieving certainty on who does what in this new field is quickly becoming fundamental to meeting essential objectives like ensuring the affordability and reliability of the electricity system. In fact, such clarity should be treated as an immediate concern of decision-makers. These key messages were top of mind in a report released by a multi-stakeholder group, the Energy Transformation Network of Ontario (ETNO), in June.

Peter Gregg, the CEO of the Independent Electricity System Operator, quickly picking up on the same themes, published an article titled “Exploring models for the effective integration of DERs,” drawing attention to the ETNO report. He outlined some of the alternative models, encouraged people to read the report, and said, “Only then can we begin the discussion, and ensure policy-makers and regulators won’t be caught by surprise — and left to figure out the rules after change has already become entrenched.”

Peter Gregg, the CEO of the Independent Electricity System Operator, quickly picking up on the same themes, published an article titled “Exploring models for the effective integration of DERs,” drawing attention to the ETNO report. He outlined some of the alternative models, encouraged people to read the report, and said, “Only then can we begin the discussion, and ensure policy-makers and regulators won’t be caught by surprise — and left to figure out the rules after change has already become entrenched.”

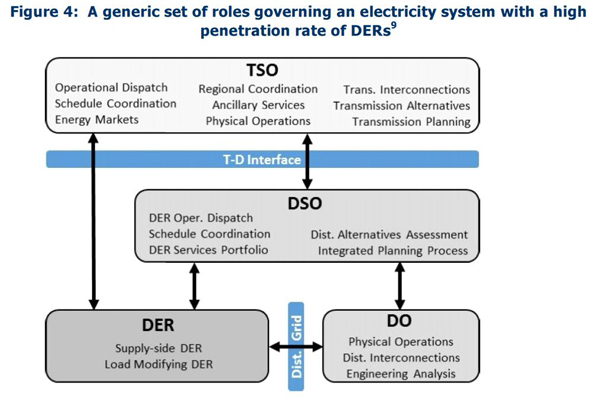

Mr. Gregg was not taking a position on who should own and control various components of the growing DER infrastructure. Neither were the authors of the ETNO report. They were clear however that the necessary technical choices cannot be made, and the high-value benefits of co-ordination cannot be achieved, until decisions are taken on the roles of key players. They are saying, in effect, that in order to make technical progress and unlock value for consumers, the institutional structure must be resolved.

Mr. Gregg stressed that “The underlying issue is the question of who should own, operate, buy and sell services related to DERs.” Pursuing the same question, the ETNO report carefully reviewed 5 alternative “development pathways” to effective local DER markets, each of which would substantially resolve the structural question. The only option that’s universally not recommended is sitting on the fence.

One key fact that may not be apparent to people outside the electricity sector is that technical questions and structural questions will inevitably be resolved on very different timelines. A quick glance at recent news stories coming out of the DER industry demonstrates that resolving technical options for development of DER-related infrastructure is an ongoing long-term process that is already benefitting from a great deal of private sector work. In contrast, setting up the institutional structure is likely to be needed only once in the lifetime of a given market design. Unfortunately, much of the technical work is currently confused and stymied by the uncertainty over the structure. As one industry observer noted, “Although technical standards will evolve over time, and regulatory rules will inevitably be refined, there is no benefit in having lingering ambiguity about the allocation of responsibilities.”

There is no telling where the system will end up, or even if there will be multiple forms for the power system in future. It’s almost like someone has taken the entire electricity system, cut it up conceptually into a million little pieces, and posted a big sign in front of the local saloon saying “Wanted: Motivated entrepreneurs to put everything together in whatever form will be most effective for the future. Active rivalries are welcome.”

The value of inter-operability

Similar issues were addressed when the wholesale electricity system was being designed more than 20 years ago. Part of the essential groundwork was deciding who would own the bulk transmission system. The case was made that wholesale competition would never work properly if one generation company owned the wires that all competitors would have to use. Separation of the wires and generation companies, the monopoly and the competitive parts of the business, was an essential feature of the competitive market design framework. In Ontario as in most other jurisdictions, complete separation was mandated prior to market opening. Although there was predictable opposition, it was one of those rare and remarkable decisions that received broad cross-sector support, from consumers to producers, and from people of all political stripes.

Similar issues were addressed when the wholesale electricity system was being designed more than 20 years ago. Part of the essential groundwork was deciding who would own the bulk transmission system. The case was made that wholesale competition would never work properly if one generation company owned the wires that all competitors would have to use. Separation of the wires and generation companies, the monopoly and the competitive parts of the business, was an essential feature of the competitive market design framework. In Ontario as in most other jurisdictions, complete separation was mandated prior to market opening. Although there was predictable opposition, it was one of those rare and remarkable decisions that received broad cross-sector support, from consumers to producers, and from people of all political stripes.

The emerging DER market offers the promise of another layer of competition at the local level. At the same time it opens analogous questions about how to make sure the existing monopoly businesses don’t impede the growth of competition. Some people would like to see the existing Local Distribution Companies (LDCs) develop, own and operate DERs. Others say such a policy would hand control to a set of vested interests, a group potentially motivated to protect their regulated rate bases, more than on maximizing competition.

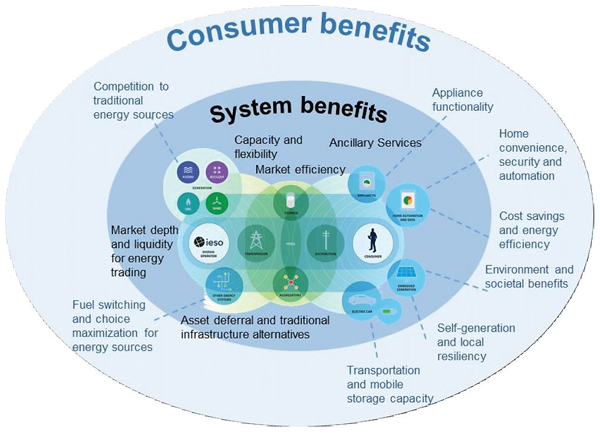

What really matters to the designers of this new infrastructure, to the IESO and to the authors of the ETNO report, is ensuring full inter-operability between all parts of the system. Inter-operability means that each part of the system can interact properly with any other part. Any piece of equipment whether it’s supply, consumption or other infrastructure, can be employed on an instant’s notice to fulfill any role that it is well suited to serve. For example, if a transformer suddenly breaks down in a city core somewhere, it should be a simple matter to automatically determine which alternative resources are immediately available to fill in, and which among those will be most cost-effective, regardless of whether the backup is another transformer, a local battery bank, spinning reserve or demand response – and regardless of who owns the backup asset or assets. State of the art control systems should guarantee the appropriate resources are used at all times, considering both reliability and cost. It should not matter if the best resource happens to be on the other side of an imaginary line (wholesale vs. retail, or supply vs. demand resources). All should be eligible to compete.

Similarly, in non-emergency situations, the local grid control system should be continually assessing what the best combination of resources would be at the moment, and impartially enabling the lowest cost choices, within the normal constraints of safety and reliability. This concept underlies recently developed frameworks for system architecture being developed by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) and others, and considered in ETNO’s research. It is also related to transactive energy system designs developed by the Gridwise Architecture Council and others.

To ensure this degree of widely extended granular control is possible, the system operators must have continual access to high quality data feeds on the state of all relevant equipment attached to the system. This kind of interoperability may seem normal when thinking about information technology. But it remains a challenge in an electric system that was largely built decades ago, before real time competition at the local level became a realistic possibility.

In an electric grid, there are interlinked layers of technical systems that need to be fully co-ordinated in order to achieve the benefits available from DERs and from the co-ordination between different parts of the system. If the operator can see all parts of the system at all times, and exercise appropriate forms of control, then consumers can be reasonably confident that the best resource will be called into service at any given time.

ETNO’s advice

ETNO characterized its central challenge saying, “Integrating DERs into Ontario’s electricity system in a way that maximizes their benefits to consumers and minimizes any negative impacts will require careful coordination of existing and new roles and responsibilities.”

Building its case for urgency, the report says, “ETNO has examined options addressing the ‘roles and responsibilities question,’ which is foundational to a multitude of second-order, technical questions that the industry will have to resolve.” Clearly, achieving interoperability is high amongst those second-order questions.

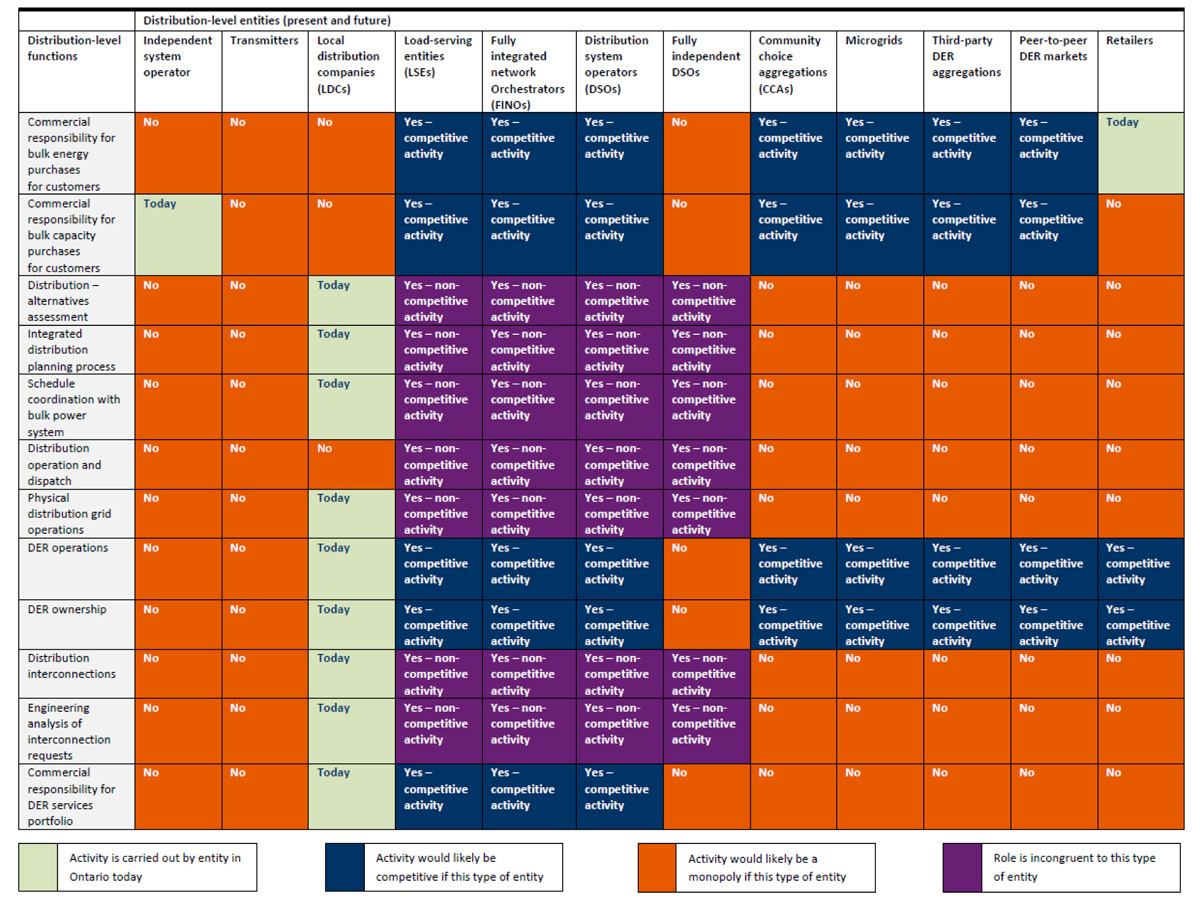

ETNO’s research specifically reviewed the prospects for each of 5 structural options:

1. Local distribution company (LDC) and today’s roles in Ontario

2. Load-serving entity (LSE), comprising several variants

3. Community choice aggregation (CCA)

4. All-encompassing distribution companies

5. Open DER markets at the distribution level, with its own variants.

While the options are numerous, agreement appears strong in certain areas. The report says, “While perspectives on the allocations of roles and responsibilities vary, ETNO members continue to agree on the importance of maximizing consumer choice through competition, market access and open reliability standards. There is also consensus on the following points:

* However responsibilities for DERs are allocated, accountabilities for electricity system reliability, security and resiliency must be clear;

* Open standards for connecting DERs to the distribution system and open access to DER markets are essential to the prevention of artificial monopolies that would otherwise stifle consumer value that would be recognized by DERs.”

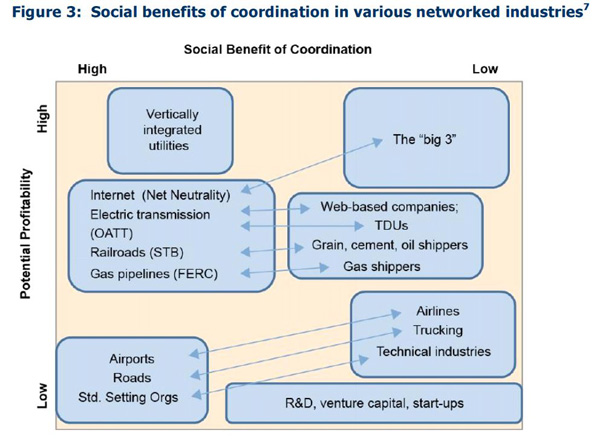

ETNO expresses one of its foundational findings like this: “At stake in this discussion is the overall customer experience with the electricity system. This includes all facets of reliability, cost, consumer choice and realization of benefits from consumer-side investment (including benefits unrelated to energy use). More than at any previous point in its history, the electricity system is truly becoming a networked industry consisting of monopolistic, competitive, regulated and unregulated components. Theoretically, there are heightened social and economic benefits to be realized from the proper coordination of these activities. Practically, the realization of those benefits will be a daunting challenge.”

Using the analogy of airport management to explain its approach to electricity system transformation, ETNO says, “As a customer, you are part of a stakeholder group that experiences the cumulative impact of how competitive, monopolistic, and regulated activities together affect the overall customer experience. In fact, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) offers airports around the world an array of services to develop core, monopoly functions as part of its ‘level of service (LoS) concept’ and ‘non-aviation business performance assessment’ to ensure that the total customer experience is maintained and enhanced. Many stakeholders in the above example benefit from the ‘network effect’ of various synergies between competitive and non-competitive activities. Clearly it makes sense for multiple airlines to make use of a common network of airports, a common protocol for routing baggage, and allowing passengers to transfer between flights and airlines through a single location. These common elements translate into efficiencies for the airlines and cost savings for the customers taking advantage of multiple flight options competing for business at each major hub. To understand the above example is to understand the approach that ETNO has applied to smart grid development over the past decade.”

Using the analogy of airport management to explain its approach to electricity system transformation, ETNO says, “As a customer, you are part of a stakeholder group that experiences the cumulative impact of how competitive, monopolistic, and regulated activities together affect the overall customer experience. In fact, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) offers airports around the world an array of services to develop core, monopoly functions as part of its ‘level of service (LoS) concept’ and ‘non-aviation business performance assessment’ to ensure that the total customer experience is maintained and enhanced. Many stakeholders in the above example benefit from the ‘network effect’ of various synergies between competitive and non-competitive activities. Clearly it makes sense for multiple airlines to make use of a common network of airports, a common protocol for routing baggage, and allowing passengers to transfer between flights and airlines through a single location. These common elements translate into efficiencies for the airlines and cost savings for the customers taking advantage of multiple flight options competing for business at each major hub. To understand the above example is to understand the approach that ETNO has applied to smart grid development over the past decade.”

Underlining the viability of open access at the local level, ETNO notes that “the European Union already requires any DSO (Distribution System Operator) with more than 100,000 customers to offer fair and open market access to third parties offering DER-related services.”

To assess the major options available, the report reviewed 6 alternative policy directions as follows:

1. The current Ontario roles and framework

2. Load-serving entities (with multiple variants)

3. Community choice aggregation models

4. All-encompassing distribution companies

5. Enforced separation of functions between distribution system operators and owners

6. Regulated separation approach.

Table 4 summarizes the roles currently played in the market today, and activities that might shift to new or proposed entities as contemplated in the ETNO report.

ETNO reiterated its longstanding support of open operational standards: “ETNO has advocated for open interoperability standards since 2011 and this issue will likely become more pressing than ever. Each interface in the increasingly complex systems environment offers the opportunity for the creation of artificial monopolies. Open standards and rules of access are one of the most important safeguards to prevent the creation of artificial monopolies and should be a key area of focus for regulators.”

Going further, this passage reads like a warning: “In Section 2 of this paper, we considered the network coordination benefits that can be realized in the interoperability layer between regulated and unregulated segments of the electricity industry. These benefits will not be realized without the correct industry structures in place. How this effort will be organized, however, leads back to the high-level policy questions that ETNO has been examining over the past several years.”

Going further, this passage reads like a warning: “In Section 2 of this paper, we considered the network coordination benefits that can be realized in the interoperability layer between regulated and unregulated segments of the electricity industry. These benefits will not be realized without the correct industry structures in place. How this effort will be organized, however, leads back to the high-level policy questions that ETNO has been examining over the past several years.”

Nonetheless, ETNO concludes that there are a number of viable options for moving though these challenges. “While some technical solutions may be more conducive than others to the policies chosen to address roles and responsibilities, for the most part, they do not constrain the policy decisions Ontario needs to make. A clear delineation of responsibilities is first required to facilitate the type of fully-integrated smart grid framework conceptualized by NIST in its smart grid interoperability framework.”

Addressing the transitional questions, ETNO says, “Given Ontario’s unique history with LDCs, the evolutionary paths examined … result in two major approaches:

1) An additive approach, where today’s LDCs take on more roles and responsibilities over time (e.g., DER commercial functions and DSO functions). …

2) An unbundling approach, in which distribution-level roles and responsibilities are divided in a manner similar to Ontario’s bulk electricity system, with individual entities responsible for market administration, poles and wires ownership, system operations and generation. In this model, LDCs would fulfil their constituent roles (e.g., wires ownership, DSO operations) and could compete with others for roles that may benefit from greater competition (e.g., LSEs, CCAs, DER ownership/operation).”

ETNO concludes its report saying, “A key next step to help guide policy-makers is to determine how roles and responsibilities for DERs may be allocated in the future. The aims should be to maximize benefits for Ontario consumers by undertaking an objective cost-benefit analysis of the options outlined, including an evaluation of the potential for stranded assets and cost shifting among consumers.”

The future may be uncertain but the next steps are reasonably clear

As Peter Gregg noted, the underlying issue is the question of who should own, operate, buy and sell services related to DERs. There are a number of ways to organize the system, but without resolution on these fundamental questions at an early stage, the important work of building integration and interoperability systems that work reliably and affordably cannot get underway.

Compared to the plethora of factors affecting the technical choices ahead, resolution of responsibilities amongst the agencies is a relatively simple matter. Much like what happened at the wholesale level twenty years ago, in each jurisdiction the responsible governing body can designate an appropriately knowledgeable regulator or impartial entity to lead an open consultation process with market design objectives and a mandate to resolve key issues on the allocation of roles and responsibilities. ETNO has mapped out much of the landscape at least for Ontario. The process will be different in each jurisdiction, and given that many jurisdictions will proceed in parallel, most will be able to learn from work done by others. The European Union, having started earlier than most, will likely be a source of valuable lessons for many others.

For further information, readers are encouraged to see the full ETNO report at this location, and the subsequent IESO discussion papers on “Distributed Energy Resources: Models for Expanded Participation in Wholesale Markets” at this location. In addition, the June 27, 2019 presentation from the IESO explaining its research objectives is here, and its project brief is here.

The picture may start out looking a little chaotic. However once rational structures enabling local markets have been instituted, the discipline of competition will likely cause virtually all participants to move into relatively efficient modes of operation in line with whatever public policy objectives are articulated. The main issue at this point is how to expedite resolution of these initial policy choices.

The APPrO 2019 conference on November 21 and 22 in Toronto will afford a range of opportunities for industry participants to examine these issues and other forces affecting the transformation of the Ontario electricity sector.

Background on ETNO

Since its establishment in 2009, the Ontario Smart Grid Forum (now ETNO) has released a series of papers containing a total of 53 public policy recommendations. Most of these recommendations were a result of dialogue between member organizations of the Forum, and its Corporate Partners Committee to reach a consensus position. These recommendations have focused on a number of issues, including:

• Maximizing consumer choice through competition

• Developing success metrics for innovation in the utilities sector

• Open access to markets and data for third parties

• Integration of DERs into the electricity system and markets

• Open interoperability standards

• Formalized, rigorous cybersecurity standards

• Physical resiliency and safety of new smart grid equipment

• Operational monitoring of DERs

With a broad cross-section of energy industry representation, private sector input from the Corporate Partners Committee, and more than a decade exploring policy options for smart grid development, ETNO is now putting forward an examination of some of the key policy options that it says “will help shape the future of our energy system.” Over the past two years, ETNO has examined various perspectives on the potential future structure of the distribution system – both inside and outside the province. This research has afforded ETNO and the Corporate Partners Committee the opportunity to understand differing points of view on this subject and explore options for mediating between them.

Members of Energy Transformation Network of Ontario

Peter Gregg, President and CEO, IESO, and Chair, Energy Transformation Network of Ontario

David McFadden, Chair, Toronto Hydro Corporation and Vice-Chair, Energy Transformation Network of Ontario

Michael Angemeer, President and CEO, Veridian Corporation

Darlene Bradley, Vice-President, Planning, Hydro One Inc.

Nicolle Butcher, Vice President Strategy & Acquisitions, Ontario Power Generation

David Collie, President and CEO, Electrical Safety Authority

Jonathan Dogterom, Practice Lead, Cleantech, MaRS Discovery District

Mark Fernandes, Chief Information and Technology Officer (CIO), Hydro Ottawa Limited

William Milroy, Vice President, Engineering and Operations, London Hydro

Dr. Jatin Nathwani, Professor and Ontario Research Chair in Public Policy and Sustainable Energy Management, Faculties of Engineering and Environmental Studies, University of Waterloo

Alexandre Prieur, Smart Grid Project Leader, Innovation and Energy Technology Sector, Natural Resources Canada (NRCan)

Neetika Sathe, Vice President, Corporate Development and Smart Grid Technologies, PowerStream Inc.

Katherine Sparkes, Director, Innovation, Research and Development, Independent Electricity System Operator

Francois Trofim, Director, Technology & Innovation, Union Gas Limited

Raymond Tracey, CEO, Essex Power

Joe Van Schaik, Electric Power Market Manager at Tormont Cat

Terry Young, Vice President, Policy, Engagement and Innovation, IESO

Observers

Karen Clark, Director, Distribution and Agency Policy, Ontario Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines

Brian Hewson, Vice President, Consumer Protection & Industry Performance, Ontario Energy Board

Further excerpt from the ETNO report

Undertaking an objective, cost-benefit analysis of the options in this report should help guide policymakers in determining how the roles and responsibilities for DERs may be allocated to maximize benefits for Ontario consumers. Given that these decisions will have consequences for Ontario residents and businesses for decades, they must be made fairly, objectively and based on evidence that supports the best interests of consumers. It is also essential that the conversation be widened to include potential new investors in the sector who will be needed to help ensure that consumers realize the full benefits of a more competitive electricity system.

Policy-makers will need to determine the point at which decisions about sector structural changes need to have been made. Many jurisdictions around the world have already embarked on this discussion. As will be discussed in Section 4, the European Union already requires any DSO with more than 100,000 customers to offer fair and open market access to third parties offering DER-related services. In Ontario, the IESO recently cited DERs as one of the largest reliability contingencies on the province’s electricity system under certain circumstances[1].

Providing specific timelines for the implementation of a particular option for distribution evolution was never the goal of this report; instead, the discussions and considerations included in this report should provide policy-makers and regulators with a starting point to examine these critical topics in greater depth.

[1] Independent Electricity System Operator (2018, December 13). Reliability Outlook: An adequacy assessment of Ontario’s electricity system from January 2019 to December 202334. http://www.ieso.ca/-/media/Files/IESO/Document-Library/planning-forecasts/reliability-outlook/reliability-outlookdecember-2018.pdf