By Dianne Saxe, Environmental Commissioner of Ontario

Ontario has a lot to be proud of. As shown in my spring 2018 report, Making Connections: Straight Talk About Electricity in Ontario, Ontario’s electrical power was 96% low-carbon in 2017. As a result, greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity sector were at an historic low, at only about 2% of Ontario’s overall greenhouse gas emissions for the year.

Ontario has a lot to be proud of. As shown in my spring 2018 report, Making Connections: Straight Talk About Electricity in Ontario, Ontario’s electrical power was 96% low-carbon in 2017. As a result, greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity sector were at an historic low, at only about 2% of Ontario’s overall greenhouse gas emissions for the year.

Not long ago, Ontario burned a lot of coal for electricity (19% in 2005) and paid for what looked like cheap power with dirty air and poor public health. Public health organizations were rightfully outraged, and all parties pledged to get rid of coal. Despite comparatively limited waterpower resources, Ontario has replaced that coal with conservation, nuclear, hydro, wind and solar, plus a small amount of natural gas. This helped produce striking improvements both in greenhouse gas emissions, and in air quality. There were zero smog days in 2014, down from 53 days in 2005.

But that needs to be just the beginning. The second part of Ontario’s low-carbon electricity transition must involve a growing role for clean electricity to replace fossil fuels in transportation and heating. And the climate crisis means that the scale and speed of the necessary transition is both urgent and daunting.

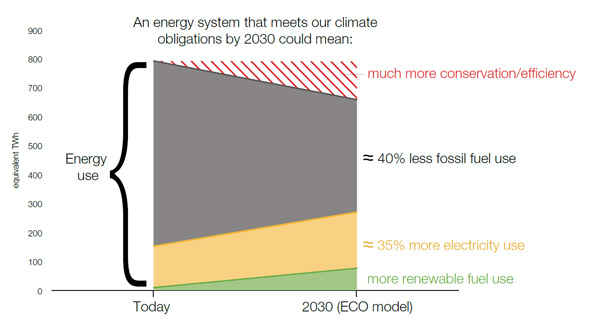

To illustrate, Ontario’s Climate Change Mitigation and Low-carbon Economy Act requires Ontario’s overall emissions to fall below 115 megatonnes by 2030 (about 31% less than 2015 levels). Not every sector can reduce emissions equally – for example, many process emissions from industry cannot be feasibly reduced with existing technology. The energy sector, which does have technological alternatives, must therefore do more than its proportional share. The ECO estimates that Ontario emissions from burning fossil fuels for energy will need to drop by roughly 45% in the next 12 years.

That’s the basic math. To get there, Ontario will need much more conservation of both fossil fuels and electricity, and renewable fuels will have a role to play. But it’s almost impossible to see a path to 2030 that doesn’t involve switching many energy uses from fossil fuels to low-carbon electricity.

Electrification will increase provincial electricity demand

The ECO has modeled one scenario that could allow Ontario to comply with its climate law and Canada’s international commitments. In this scenario, even with more electricity conservation than targeted in the Long-Term Energy Plan (LTEP), annual electricity demand in 2030 would grow to roughly 194 TWh. That’s more than a one-third increase in electricity over Ontario’s 2016 demand (142.9 TWh, including both transmission-connected and embedded generation). It’s also about one-third more electricity than the LTEP predicts Ontario will use in 2030. In other words, the LTEP is planning for failure. Ontario will almost certainly break its climate law without a significant increase in electricity use in the next 20 years.

The ECO has modeled one scenario that could allow Ontario to comply with its climate law and Canada’s international commitments. In this scenario, even with more electricity conservation than targeted in the Long-Term Energy Plan (LTEP), annual electricity demand in 2030 would grow to roughly 194 TWh. That’s more than a one-third increase in electricity over Ontario’s 2016 demand (142.9 TWh, including both transmission-connected and embedded generation). It’s also about one-third more electricity than the LTEP predicts Ontario will use in 2030. In other words, the LTEP is planning for failure. Ontario will almost certainly break its climate law without a significant increase in electricity use in the next 20 years.

If Ontario does want to comply with its climate law, where can the extra low-emission electricity come from? The nuclear refurbishments at Darlington and Bruce are already built into the LTEP, i.e., to meet projected levels of demand without significant electrification. Some additional supply can come from making better use of Ontario electricity that is currently exported (13.9 TWh in 2016, net) or curtailed (7.8 TWh in 2016), and from storage and other tools, including pricing, to better match electricity supply and demand. But new low-carbon generation will also be needed.

Electrification will affect not only overall electricity use, but also peak demand. Electrification of transportation holds much promise to reduce the daily peaks in electricity demand if Ontario can time most electric vehicle charging overnight. On the other hand, electrification of heating brings a risk of increasing peak demand on cold winter days and nights – a risk that will need to be carefully managed.

The role of Market Renewal

Meanwhile, the Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) is planning to redesign Ontario’s electricity markets. Market Renewal is intended to expand the role and improve the functioning of markets, while moving away from long-term, technology-specific contracts to get new electricity generation resources built. One way of thinking about it is: Market Renewal is intended to drive down the much-hated Global Adjustment.

One of the key risks of Market Renewal is whether it will provide Ontario with new sources of low-carbon electricity. In the early 2000s, the last time Ontario tried to move so strongly towards markets to supply electricity, prices rose sharply and there was huge concern about adequate supply. Former Premier Eves struck a high level Electricity Conservation and Supply Task Force, which strongly recommended long-term contracts to get new resources built. The 2004 Task Force report explained its rationale in detail.

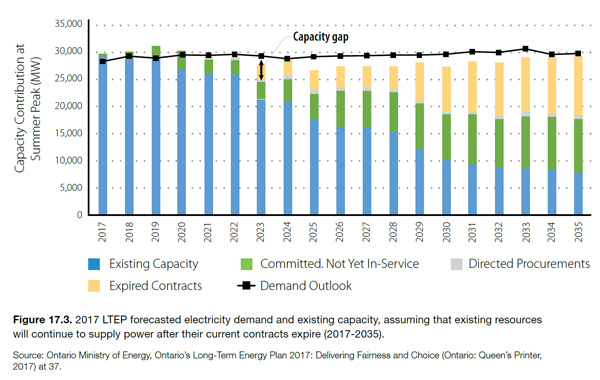

Today, those lessons seem to have been forgotten. The IESO is proposing to procure capacity through a new Incremental Capacity Auction, which will offer bidders only short-term contracts. The IESO anticipates being able to dip its toes into the capacity market slowly, with the first auction looking for a small amount of incremental capacity that will probably not require new generation (e.g., generators with expired contracts, capacity upratings at contracted generators).

This model might help keep costs down if electricity demand stays flat, at least for a while, although it may not keep greenhouse gas emissions down. Many existing electricity generation facilities have contracts that will expire in the 2020s, but will still have remaining useful life. If all these generators participate in the capacity auction, this would fill most, but not all, of the LTEP’s projected future capacity gap, i.e., if demand stays flat.

2017 LTEP forecasted electricity demand and existing capacity, assuming that existing resources will continue to supply power after their current contracts expire (2017-2035).

Source: Ontario Ministry of Energy, Ontario’s Long-Term Energy Plan 2017: Delivering Fairness and Choice (Ontario: Queen’s Printer, 2017) at 37.

However, in a world where electricity use must grow, and most of that electricity needs to come from low-emission electricity resources, this type of pure market mechanism seems likely to produce adverse results. For one thing, as Ontario’s 2002 and 2005 experience showed, markets can produce shockingly high prices when demand is high. For another, a capacity market on its own is unlikely to bring on new renewable generation, which has high capital costs that take years to pay back. A pure capacity auction is more likely to procure gas-fired generation, because capital costs are low in exchange for much higher operating costs and emissions. Carbon pricing through cap and trade will provide a small amount of additional revenue for low-carbon resources in the wholesale electricity market by increasing the market-clearing price when gas-fired generation is at the margin. But it won’t provide much – at least not at the current carbon price.

Can some combination of revenue streams from the capacity market, the wholesale electricity market, and ancillary markets effectively incent development of new low-carbon resources? Is there a role for additional conservation, beyond demand response, in Market Renewal? The work of the IESO’s Market Renewal working group, the Non-Emitting Resources Subcommittee, may provide some answers.

If Ontario is to meet its climate obligations, it will need many more new low-carbon electricity resources than the Ministry of Energy and the IESO are planning for, or than Market Renewal, as currently described, seems likely to produce. With the scale of change that will be needed by 2030, Ontario does not have much time to get this right.