According to the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, the province’s approach to its Long Term Energy Plan needs to change substantially in order to meet current environmental and public consultation standards.

Dianne Saxe, the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, delivered a remarkably tough and direct critique of the province’s approach to preparing its Long Term Energy Plan (LTEP) as part of her address to the APPrO 2016 conference in Toronto on November 16. Identifying serious deficiencies in the areas of greenhouse gas emissions, contingency planning, and public consultation, Ms Saxe also tabled preliminary recommendations which she and her staff believe could help to address the weaknesses in the energy planning process.

No public policy decisions have greater consequences for the environment and climate policy than energy planning choices, Ms Saxe said. “The LTEP is going to govern 70% of our (GHG) emissions.”

Ms Saxe focused on three primary issues with the LTEP and its supporting documents:

1. Ensuring the LTEP is consistent with established GHG reduction targets,

2. The need for explicit contingency planning to manage supply risks, and

3. The adequacy of the public consultation process.

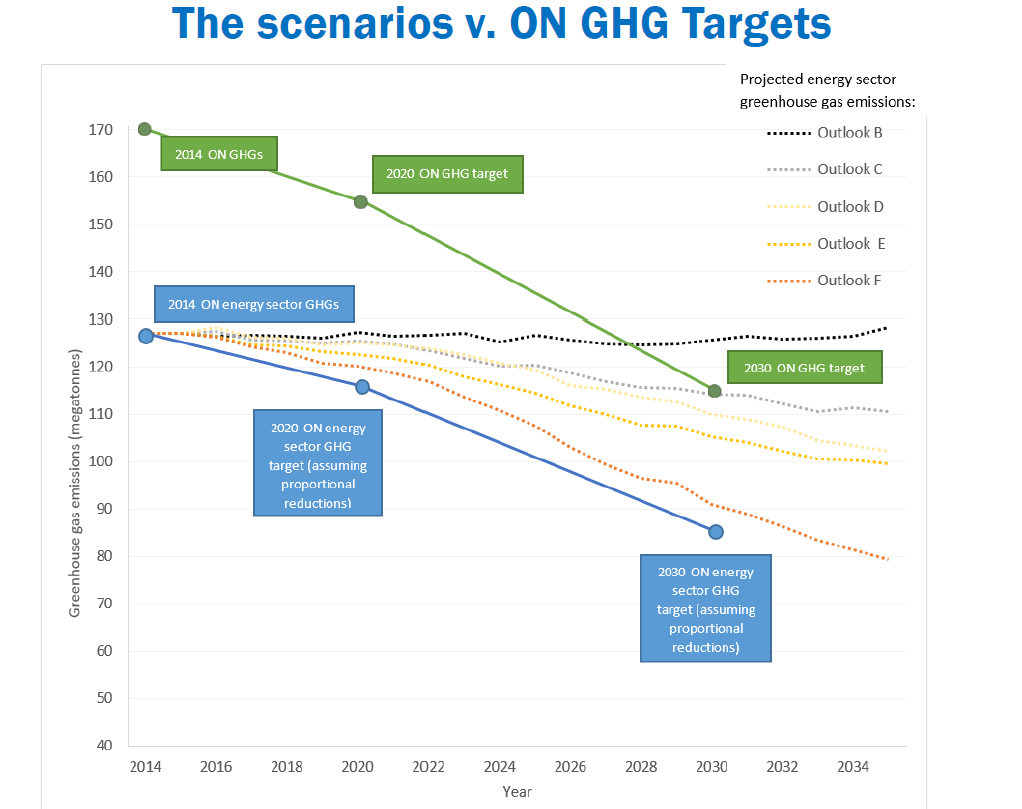

On climate change mitigation targets, Ms Saxe was stark: “None of the (LTEP) scenarios, none of them, meet the climate targets.” Noting that, “There are strong and challenging targets for provincial GHG emission reductions in the Act,” meaning the Climate Change Mitigation and Low-carbon Economy Act, 2016, she cited recent research indicating that even the existing target of 80% reduction by 2050 will not be sufficient to keep global warming to 2 degrees or less. At the same time she acknowledged that electricity generation is not a major contributor to Ontario’s GHG emissions, describing it as “the smallest and cleanest” of the energy-related sources of GHG emissions. Energy used in transportation and buildings are much more significant causes of GHGs (greenhouse gases) than power production in Ontario, suggesting that deeper emissions reductions from these sources are needed in the LTEP.

Projected energy sector emissions (fuels and electricity combined) under scenarios described in technical report, in comparison with ON 2020 and 2030 targets, and proportional targets for the energy sector.

Projected energy sector emissions (fuels and electricity combined) under scenarios described in technical report, in comparison with ON 2020 and 2030 targets, and proportional targets for the energy sector.

Raising an issue of particular interest to the power generation industry, Ms Saxe highlighted the need for a well-developed contingency plan to cover potential supply risk. One of her key recommendations is to “Provide details on plans to hedge against major nuclear-related energy supply risks: uncertainty surrounding the Pickering license extension, and the potential for cost overruns and delays/cancellations in nuclear refurbishments.” She notes that, “The OPO does not indicate at all how it would address cost overruns or a license extension application denial, but simply suggests that there would be time to develop alternatives should one of these situations occur.” The OPO, or the Ontario Planning Outlook, is a key part of the discussion material distributed by the Ontario government in its public consultations on LTEP.

“Pickering might get its license extended. What if it doesn’t?” Ms Saxe asked. “What if the OEB won’t give the price increase? What if the nuclear regulatory safety agency won’t extend the license? What are we going to do then? The government seems to simply assume that it’s all a fait accompli. It’s not a fait accompli. There needs to be a serious contingency plan and there should be public consultation on that contingency plan.”

As APPrO members and others have pointed out, in the absence of a well-developed contingency plan, the province could face supply shortages, unnecessarily expensive replacement power sourced on relatively short notice, and additional atmospheric emissions. Many are saying that a full comparison of costs and benefits of all the realistic alternatives should be part of the public consultations on the LTEP, rather than waiting until a need is apparent, by which point it could be too late to properly compare options or to develop the most attractive options.

Crucial information is missing from the documents on which the official LTEP public consultation is based, Ms Saxe says. “There is no proposal for detailed documentation of the environmental footprint of any of these supply mixes. There is no proposal for meaningful public consultation (on the actual plan). We are having a discussion guide with no content on the EBR. And that seems to me the government’s intention to be the only consultation. When you drive through decisions that have no public legitimacy, do they stick in the long run? Does it make you as an industry better off for the government to try to force through decisions that the public won’t accept?”

In terms of public oversight with respect to energy planning, Ms Saxe’s comments were particularly pointed. “We had a legal system for overview of energy planning, the energy system, which was almost entirely ignored …. It really undermines a sense of public legitimacy when the government system not only ignores public input but positively breaches the governing law on how energy system decisions are to be made. Needless to say our office has been critical about this for a number of years. … In the meantime the Ministry of Energy just keeps issuing directives.”

The province’s use of directive powers is related to these weaknesses in the planning process, Commissioner Saxe suggested. In her presentation, she noted that “The extensive use of the directive power to make policy has reduced the opportunity for public input into electricity policy. It has also created a vacuum in accountability and oversight of the OPA’s actions in response to directives. Little discussion of either the government’s direction to its electricity planning agency or agency’s response has occurred in the public domain.”

In addition to these concerns, the Environmental Commissioner expects to address further issues in its LTEP comments including “putting conservation first,” and clarifying the process for review of other environmental impacts of the LTEP in addition to GHGs.

Summarizing her thinking, Ms Saxe said, “If you don’t have public consultation, if you don’t have transparent evidence-based decision-making that key stakeholders can challenge in a meaningful way, you don’t end up with a defensible public process that the public is likely to accept.”

The Environmental Commissioner of Ontario (ECO) is an officer of the provincial legislature, with wide scope to review and comment on public policy and government programs. Like an auditor general, the ECO is responsible for serving all three parties and the public with reliable facts and analysis. Ms Saxe has held the position of Environmental Commissioner for 11 months.

Dianne Saxe has been rated as one of the world’s top 25 environmental lawyers, according to Best of the Best, 2008, and Lexpert’s Guide to the 500 Leading Lawyers in Canada. Awards have included Ontario Bar Association Distinguished Service Award and the Osgoode Hall Lifetime Achievement Gold Key.

The ECO released its annual report on climate change on November 22, and plans to issue a special report specifically on LTEP in early December.