By Stephen Kishewitsch

Power project development hasn’t always heeded the concerns of its Indigenous hosts and neighbours. In years past, provincially-owned utility or a private company could appear on Aboriginal traditional territory with a development project, and the community might not even have been informed. Traditional lands and resource areas might be drowned by the impoundment of a hydro project. The project would be experienced as an insult to rights and sovereignty. The response might be road blockades, and court injunctions would be sought. If there were benefits, it often amounted to construction jobs and training, and in some cases a retroactive cash settlement.

Power project development hasn’t always heeded the concerns of its Indigenous hosts and neighbours. In years past, provincially-owned utility or a private company could appear on Aboriginal traditional territory with a development project, and the community might not even have been informed. Traditional lands and resource areas might be drowned by the impoundment of a hydro project. The project would be experienced as an insult to rights and sovereignty. The response might be road blockades, and court injunctions would be sought. If there were benefits, it often amounted to construction jobs and training, and in some cases a retroactive cash settlement.

Things have changed, thanks in part to several rulings that wound their way over the years to the Supreme Court. Power utilities and private developers have shown themselves increasingly receptive to the supporting the needs and ambitions of Aboriginal communities.

Industry practice has perhaps entered a new phase of evolution, with the formation of a number of full partnerships in power projects across the country. Ownership and shared control of a facility's design and operation are generally viewed as an improvement both for indigenous communities and for the project itself.

We examine below some of the prominent projects with Aboriginal ownership, a range of noteworthy initiatives, provincial programs, and an overview, province by province, of key developments in the area.

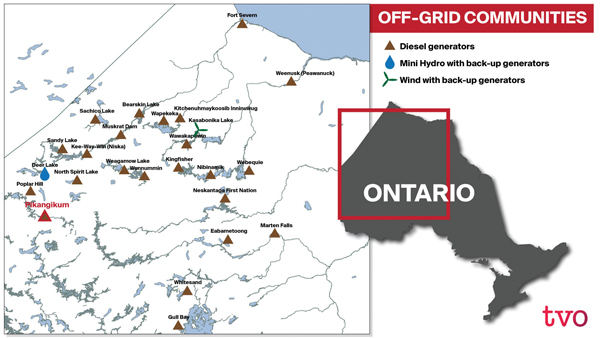

Beginning in Ontario, a new transmission project may have reached a size record in Canada for a megaproject initiated by First Nations in a full partnership with industry. In August the Ontario government designated Wataynikaneyap Power, a partnership between Fortis and RES Canada and 22 First Nations in northwestern Ontario, as the company to develop and own a $1.35 billion transmission line into a region of the province that has never been connected to the grid. The line, 1800 kilometres in total, will, in its first phase, run north from the connection point east of Dryden, Ontario to Pickle Lake, and in phase two branch out to provide 16 communities with their first grid power and relieve them from their current dependence on expensive, polluting, and less than completely reliable diesel.

Beginning in Ontario, a new transmission project may have reached a size record in Canada for a megaproject initiated by First Nations in a full partnership with industry. In August the Ontario government designated Wataynikaneyap Power, a partnership between Fortis and RES Canada and 22 First Nations in northwestern Ontario, as the company to develop and own a $1.35 billion transmission line into a region of the province that has never been connected to the grid. The line, 1800 kilometres in total, will, in its first phase, run north from the connection point east of Dryden, Ontario to Pickle Lake, and in phase two branch out to provide 16 communities with their first grid power and relieve them from their current dependence on expensive, polluting, and less than completely reliable diesel.

The name means “line that brings light” in Anishiniiniimowin, named by the elders who provided guidance to the partners. The Fortis-RES Partnership will work with the First Nation-owned Wataynikaneyap Power to manage the partnership and invest in the project, while the 22 First Nations will remain majority owners and have the option to become 100% owners over time.

The name means “line that brings light” in Anishiniiniimowin, named by the elders who provided guidance to the partners. The Fortis-RES Partnership will work with the First Nation-owned Wataynikaneyap Power to manage the partnership and invest in the project, while the 22 First Nations will remain majority owners and have the option to become 100% owners over time.

Tasked by their communities with developing the transmission themselves, the decision evolved by 2012 into an agreement with 13 First Nations, reaching the current 22 this past summer.

The partnership started lobbying hard to get those remote communities connected to the grid. A lot of it involved making presentations on the conditions in those communities, and how compromised they were. It’s not just that they didn’t have light in the evening. A shortage of reliable power affects all basic needs – food, water and shelter. It puts a chokehold on economic development opportunities, all due to the lack of proper infrastructure.

“We have houses being built, but they can’t be powered because the existing diesel power supply can’t keep up with the extra demand. We can’t open up new businesses.

“It was about the development of a vision of ownership and control of any major infrastructure that comes into our territory,” Ms Kenequanash said. “It meant a huge learning curve, first for ourselves – we had to educate ourselves and educate our communities, then we had to educate government and industry, to create an understanding of what that means. That was another challenge on its own. Creating an infrastructure owned by First Nations was not within the parameters of existing legislation, policy and everything else, so we had to work through a lot of processes to enable that to happen. We wanted to change the landscape of how we do business with industry and government. We spoke with at least 6 candidate companies, and settled on RES Canada and Fortis they were the most prepared to support First Nation ownership. Most of the other companies were willing to build the line for us, and provide the usual benefits [the historic pattern has been jobs, training and a monetary compensation package], but expected to own the line themselves.”

Only three seemed open to the idea of joint partnership, she says, and of those RES Canada and Fortis looked like the best choice.

Backed by a series of legal decisions, including the 2014 Supreme Court reading on the meaning of consultation, in the Tsilqot’in case, she said. “... I told everyone that if they wanted the line built, they can’t do it without the FNs. They would have to engage as equals with FNs from the outset or there would be conflict, and government would have to support us.”

The First Nation partners believe the line will open up new possibilities. There are 6 possible sites in the area that have been identified, not counting solar and small wind. They’re mostly hydro power, with a combined potential capacity of 200MW, but they haven’t been developed because they’re too far from any existing line. The line can open that possibility up, though the IESO cautions that whether a procurement will be available to purchase that supply will be dependent on system need and government policy. If it does, we can now expect it to be developed with First Nation partnership as well.

“In this day and age, with all the commodities that are available, why should our people, the original inhabitants of the land, and who should be wealthy, be going without? This is a wonderful, win-win project for everyone.”

Comparable in size is the $2.6 billion Lower Mattagami hydropower project, by Ontario Power Generation, in partnership with the Moose Cree First Nation (cover photo). The facility has added 438 MW of new capacity. The Moose Cree have a 25 per cent equity share in the new generating units.

OPG has also retroactively reached a partnership with the Lac Seul First Nation in northwest Ontario, over hydro facilities built on traditional lands of the First Nation on the English River system near Ear Falls, between 1930 and 1948. As Don Brazier at OPG writes in the blog of the Canadian Electricity Association, Lac Seul now has a 25% ownership in the 12.5 MW Lac Seul generating station.

Honourable mention among recent developments must go to the recently-completed Gitchi Animiki Hydro Project, two generating stations (Gitchi Animki Bezhig & Gitchi Animki Niizh) with a combined capacity of 18.9 MW. The project is owned by the Pic Mobert Hydro Power Joint Venture, a 50/50 joint venture of subsidiary companies of the Pic Mobert First Nation and Regional Power. Pic Mobert and the Ojibways of the Pic River have been pioneers in pursuing their own projects, such as a 22.8 MW run-of-river hydropower facility on the White River at Umbata Falls, between the Ojibways of the Pic River and Innergex, construction beginning in 2005. Dokis First Nation's hydro project would be another good example, and the Batchewana First Nation is a 50–50 partnership with BluEarth Renewables in the 58.32 MW Bow Lake Wind Facility, located in the Algoma district. The windfarm went into service in 2015.

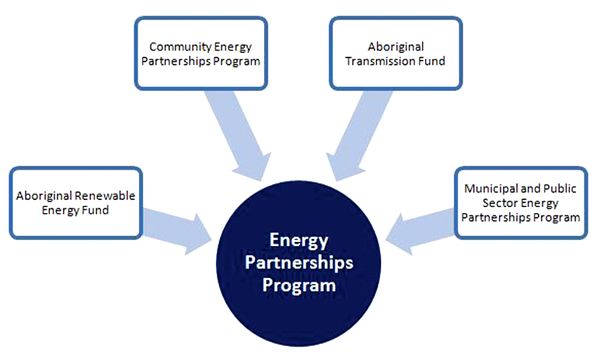

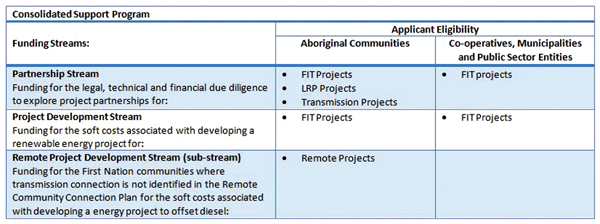

The Ontario government mandate has established several programs to assist Indigenous communities with capacity-building and early development costs:

• The Partnership Stream

For Indigenous communities, funding for the legal, technical and financial due diligence work to develop partnerships on Feed-in Tariff (FIT), Large Renewable Procurement (LRP) and identified transmission projects.

• The Project Development Stream

Funding for Indigenous communities, municipalities, co-operatives and public sector entities to assist with the soft costs associated with developing FIT projects, such as obtaining the requisite regulatory approvals.

This stream also includes a Remote Project Development Sub-Stream – available to identified remote First Nations communities (those that have been identified as uneconomic to connect to the IESO-controlled grid) – to assist with costs for developing energy-based solutions to reduce diesel dependency in these communities.

The EPP amalgamates four separate former funding programs – the Aboriginal Renewable Energy Fund (AREF), the Community Energy Partnerships Program (CEPP), the Municipal and Public Sector Energy Partnerships Program (MPSEPP), and Aboriginal Transmission Fund (ATF) – of which some First Nation project proponents have accessed in the past (AREF and ATF). The EPP and its predecessors combined have supported 776 projects and have leveraged over $20 million in secured funding to date.

Wuskwatim Generating Station

There is also the $650 million Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program, under the Ontario Financial Authority, which supports Aboriginal participation in new renewable green energy infrastructure in Ontario including wind, solar and hydroelectric.

Wuskwatim Generating Station

There is also the $650 million Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program, under the Ontario Financial Authority, which supports Aboriginal participation in new renewable green energy infrastructure in Ontario including wind, solar and hydroelectric.

Manitoba

Wuskwatim GS under construction

Manitoba comes close behind Ontario in the size of two recent projects in partnership with First Nations, the completed 200 MW Wuskwatim GS, in production since 2012, and the 695 MW Keeyask generating station, at which earthworks and concrete pouring are underway as this article is being written. Both partnerships are with Manitoba Hydro, which calls Wuskwatim “the first time in Manitoba and Canada that a First Nation and an electric utility have entered into a formal equity partnership to develop and operate a hydroelectric project.”

Wuskwatim GS under construction

Manitoba comes close behind Ontario in the size of two recent projects in partnership with First Nations, the completed 200 MW Wuskwatim GS, in production since 2012, and the 695 MW Keeyask generating station, at which earthworks and concrete pouring are underway as this article is being written. Both partnerships are with Manitoba Hydro, which calls Wuskwatim “the first time in Manitoba and Canada that a First Nation and an electric utility have entered into a formal equity partnership to develop and operate a hydroelectric project.”

The Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation has a 33% equity stake in the Wuskwatim Power Limited Partnership with Manitoba Hydro. The Keeyask Hydropower Limited Partnership consists of the Tataskweyak Cree Nation, War Lake First Nation, York Factory First Nation, and Fox Lake Cree Nation, together with the General Partner, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Manitoba Hydro. The Keeyask partners will have up to a 25% stake, although they still have some time before the station goes into production to decide on its exact structure.

The Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation has a 33% equity stake in the Wuskwatim Power Limited Partnership with Manitoba Hydro. The Keeyask Hydropower Limited Partnership consists of the Tataskweyak Cree Nation, War Lake First Nation, York Factory First Nation, and Fox Lake Cree Nation, together with the General Partner, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Manitoba Hydro. The Keeyask partners will have up to a 25% stake, although they still have some time before the station goes into production to decide on its exact structure.

Manitoba Hydro has and continues to provide construction, management and operational services to both partnerships and generating stations. But there is a board, with both Manitoba Hydro and Cree representation, that oversees the Wuskwatim facility's operation, that meets on a quarterly basis and reviews the way the business is going.

Manitoba Hydro has and continues to provide construction, management and operational services to both partnerships and generating stations. But there is a board, with both Manitoba Hydro and Cree representation, that oversees the Wuskwatim facility's operation, that meets on a quarterly basis and reviews the way the business is going.

For what has become the Keeyask project, Tataskweyak Cree Nation (TCN) and War Lake First Nation (WLFN) formed the Cree Nation Partnership (CNP) in 2001 because of their common interest in future hydro-electric development on the Lower Nelson River. Today, they point out, there are four generating stations in the Split Lake Resource Management Area – Kelsey, Kettle, Limestone and Long Spruce – which produce just over 75% of the power produced in Manitoba.

For what has become the Keeyask project, Tataskweyak Cree Nation (TCN) and War Lake First Nation (WLFN) formed the Cree Nation Partnership (CNP) in 2001 because of their common interest in future hydro-electric development on the Lower Nelson River. Today, they point out, there are four generating stations in the Split Lake Resource Management Area – Kelsey, Kettle, Limestone and Long Spruce – which produce just over 75% of the power produced in Manitoba.

Lorne Midford, Chair of both the Wuskwatim and Keeyask partnerships, echoes Margaret Kenequanash: "It’s in their traditional territory. You either reach out and make it a win-win proposition, or the plant doesn’t get built. You need the community acceptance, the social piece of it. It’s in their back yard, it affects their way of life. There has to be a positive for them.” In this case, he says, Manitoba Hydro on its own made the decision to pursue a partnership. The engagement on Wuskwatim with First Nations began right from the planning stage.

“There were some initial design decisions about the capacity output – there was an opportunity to build a bigger plant there, which would have been better from a business perspective, but it would have caused more flooding," he explains. As it is, the project flooded less than half a square kilometre, all contained within the immediate forebay area. Given Manitoba's lack of deep river valleys, where a high dam can generate a high head and more power, a high dam would also have flooded an additional 140 square kilometres. Instead, "... Together with our partners we came up with a low head, lower output plant that had lower impact on their way of life, and I think it was the right decision. We had an agreement with them in place and included them in the planning. Our licensing was based on traditional science but also aboriginal knowledge.”

“At Wuskwatim there’s an ongoing environmental monitoring phase, which is carried out by the First Nations. They have their own company that works on the ongoing monitoring.”

The duty to consult was not an extra imposition, he says: “You can’t get better consultation than by having a partner.”

Even so, that enlightened attitude was also the product of a learning experience from earlier projects, said Chief Marcel Moody of the Nisichawayasihk Nation in a phone interview.

"When Manitoba Hydro did the Churchill River Diversion project [construction contracts were awarded in 1973], at that time the laws were different, the consultation process was quite different. Basically they came in, said this is what we're going to do and did it. We experienced massive flooding of our territory 30 – 40 years ago. Now, I think the corporate mentality has changed. I think their values have changed. You can't just do whatever you want any more. The Tsilqot'in decision and others have made a difference in being able to have authority over what happens on our traditional territory. People and companies generally respect that, and so we have opportunities because of it. They see us as having the resources to do that. That's the intangible that being a partner in a megaproject brings to our nation. It creates opportunities for us. It's made a difference."

Liz Carriere, who began working some sixteen years ago on the financing of the Keeyask partnership from the Manitoba Hydro side, explains that the First Nation partners have a couple of options, which they are still considering. With projects of this size, where the capital investment runs into the hundreds of millions – and this is true of several of the projects being described here – the First Nation partners typically don't have access to financial resources of that scale, either internally or through access to a lender community that typically may never have seen them come in the door before. Accordingly, while the community may be able to come up with a few million from their own resources, the bulk of the financing is also typically arranged through the provincially-owned utility or the private developer, with its more extensive resources.

"Manitoba Hydro is prevented by its governing legislation from disposing of any assets. We had to establish the units up front. So we set it up at the outset that they [the Keeyask partners] would have 17.5% outright, of which they put in $2.5 million of their own and up to an additional $22.5 million when the generating station goes into service. Manitoba Hydro is lending the rest, and will take a proportion from the revenue to pay down the outstanding loans and interest. The partners have the option of an additional buy-in, up to 25%, at a later date.

"Then, because the length of construction on a project like this is so great, by the time the plant goes into service, these facilities are known for having very volatile earnings. You have a fixed cost, and you can't control the level of water from year to year, so the earnings are very variable. The common shares take whatever is left over after paying off all the costs, including the interest. That's what's available as a dividend payment. As a result there's so much uncertainty over the revenues as well as the ultimate capital cost, that they didn't want to make the decision at the outset as to what kind of investment to make. So we created a preferred unit holder, that takes away the front end risk. It reshapes distribution so they get more at the front end and less at the back end."

The four First Nation partners have up to 6 months after the final unit, the seventh, is in service to decide what form they want their investment to take. At that point they will have certainty as to the ultimate capital cost, and a fair idea of the price they will receive for electricity.

Québec

Québec may be best known in some recollections as the site of the immense James Bay hydro projects, on the La Grande and Grand Baleine river systems (the latter of which is still under construction, in-service date scheduled for 2020) and the Rupert River diversion. The James Bay project drew fierce resistance from the James Bay Cree people, leading to a $225 million settlement agreement, managed by three native-owned development corporations: The Cree Board of Compensation, the Makivik Corporation and the Naskapi Development Corporation, for native economic development. In the era, that marked the extent of collaboration with First Nations.

That was then. A couple of recent developments would indicate a newer trend.

The Mesgi'g Ugju's'n (MU) Wind Farm, "big wind" in Mi'gmaq is a 149.25 megawatt wind farm currently under construction in the Gaspé region. The wind project is owned and developed in a 50-50 partnership between the three Mi’gmaq First Nations (Listuguj, Gesgapegiag, Gespeg) and Innergex Renewable Energy. The wind farm is expected to be operational in late 2016. The partners control the project in equal measure – the board of Mesgi’g Ugju’s’n (MU) Wind Farm, L.P. is made up of four representatives of the Mi’gmaq communities and four representatives of Innergex.

The Mesgi'g Ugju's'n (MU) Wind Farm, "big wind" in Mi'gmaq is a 149.25 megawatt wind farm currently under construction in the Gaspé region. The wind project is owned and developed in a 50-50 partnership between the three Mi’gmaq First Nations (Listuguj, Gesgapegiag, Gespeg) and Innergex Renewable Energy. The wind farm is expected to be operational in late 2016. The partners control the project in equal measure – the board of Mesgi’g Ugju’s’n (MU) Wind Farm, L.P. is made up of four representatives of the Mi’gmaq communities and four representatives of Innergex.

Groundbreaking ceremony for the Mesgi'g_Ugju's'n windfarm

The Migmawei Mawiomi Secretariat (MMS) is an organization that represents the three Mi’gmaq communities located on the territory of Gespe’gewa’gi: Gesgapegiag, Gespeg and Listuguj. An essential component of its mandate is to ensure community access to resources in order to benefit from economic growth.

Groundbreaking ceremony for the Mesgi'g_Ugju's'n windfarm

The Migmawei Mawiomi Secretariat (MMS) is an organization that represents the three Mi’gmaq communities located on the territory of Gespe’gewa’gi: Gesgapegiag, Gespeg and Listuguj. An essential component of its mandate is to ensure community access to resources in order to benefit from economic growth.

For the three Mi’gmaq communities, the partnership with Innergex is the first agreement undertaken with an energy company, and its goal is to enable them to fully participate in local development of wind power.

Innergex, an independent renewable power producer based in Québec, will oversee the development, construction and management of the wind farm. The company already owns and operates six wind farms in the Gaspé Peninsula and in the Lower St-Lawrence regions.

Troy Jerome, Project Director for the project, described the experience from the Mi’gmaq side. One factor seems to be common to all these stories, a very steep learning curve, gaining the expertise to deal with legalities, contracts and power system technicalities.

“The three communities formed a political assembly in 2000, and spent the next three to five years pushing on the provincial government for 3-5 years to develop the project, then created a special purpose vehicle for the project, the MU Board.

“We bid unsuccessfully on a couple of projects with the government of Québec in 2000. We finally met with the vice-Premier in 2008, and told them ‘we’re leaving now, and the next time you see us we’ll be experts in wind energy.’ And we went and educated ourselves. Then we started going back to the Québec government and demanding our fair share.

“We went it alone as far as we could without a partner, because in those earlier days any partner would expect more of the ownership and control for themselves. So for us to have control, and as much of the benefit as possible, we kept the developers on the outside. But when they saw we were getting more and more traction with the Québec government, and it looked like we were going to have a windfarm, then ten to twelve companies started courting us. We told them to go away for a while and stop bothering us, we’re going to consider you, just wait a bit.”

An Aboriginal Energy Fund from Aboriginal Affairs Canada provided some up-front money for wind test towers and technical evaluations of the resource.

“At a given point the government said, ‘in order to take you seriously, we need to see that you can finance and develop your project.’ So we put out an RFP to the energy companies, with some requirements for them to meet. At the end it came down to two or three, we asked them to show us some financial projections and what the relationship would look like, and we chose Innergex. But it was driven from the Mi’gmaq side. We wanted to be able to choose the turbines, how we’re going to finance it, and who would do the construction. And we wanted to learn in the process. We want to grow our economy over the next few decades. We will be doing other projects, and will need to borrow another $100-200 million somewhere else. Now we can see what that looks like. We want to be taken seriously.

“Bringing the Québec government around to the point where the community could itself develop and have ownership of a wind project was the second-hardest job. It was days and days of meetings with representatives at all levels, up to the Premier. In the end what made the difference was that we were able to put a clear project in front of them.

“We also told all the interested developers that all those projects on that had already been done on our territory have a huge hole in them, because the community hadn’t been consulted on them.”

Nor are the Mi’gmaq alone. The Innu Nation in northern Québec is developing a partnership with Boralex on the 200 MW Apuiat wind farm project in the municipality of Port-Cartier in Québec's Côte-Nord region. At the time of this writing key details remain to be negotiated, but once again an equity stake is being considered.

In further news, Nimschu Iskudow Inc., a First Nation-owned company in the community of Whapmagoostui, the northernmost Cree community in Québec, has proposed a new remote micro-grid system to replace the three 1.1 MW diesel generators that provide all the power in the area. Whapmagoostui, “Place of the beluga,” is home to approximately 900 Cree. About 650 Inuit live in the neighbouring village of Kuujjuarapik. Neither community is connected to Hydro-Quebec’s electrical network. As with all communities dependent on diesel for power, escalating costs and environmental impacts have been an on ongoing concern. Furthermore, the gensets are approaching the end of their design life. The micro-grid would provide renewable power to both communities, reduce the cost of generation and improve power quality and grid stability.

EcoEII contributed $700,275 towards a Front End Engineering and Design (FEED) study, to determine the technical and economic feasibility of such a system in northern conditions. A detailed study has been undertaken to optimize the topology of the system. Negotiations with Hydro-Québec for a Power Purchase Agreement are ongoing.

The above stories from Ontario, Manitoba and Québec would be the big news, but there are some developments in other provinces as well.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Labrador is of course the site of a hydro megaproject at Muskrat Falls on the lower Churchill River. The provincial government has concluded benefits agreements with the Inuit communities that provide financial compensation and other benefits in return for use of the resource. However, for this article, IPPSO FACTO is unaware of any projects involving full equity partnerships with First Nations.

The provincial government states as follows, in part, on its website:

"In 2013, the provincial government released the Aboriginal Consultation Policy (ACP) which outlines how government will conduct Aboriginal consultation on land and resource development decisions. The provincial government has also incorporated resource revenue sharing and Impacts and Benefits Agreements (IBAs) policies into the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (LILCA), and the Innu Land Claim Agreement-in-Principle.

"In November 2011, Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nalcor Energy and the Innu Nation signed the Tshash Petapen, or New Dawn Agreement. The agreement comprised three documents: the Land Claim and Self-Government Agreement-in-Principle, the Upper Churchill Redress Agreement and the Lower Churchill Innu Impacts and Benefits Agreement. Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Innu Nation are currently negotiating a Final Land Claim based on the Agreement-in-Principle. The settlement of the Final Land Claim will provide the Innu with self-government authority in certain areas, as well as clarity regarding ownership and management of lands and resources."

Nova Scotia

"Nova Scotia is a little slower to the game than some of the other provinces," said Terrence Toner at Nova Scotia Power, in reply to a phone query. "We have had some intermittent project interactions with First Nations over the years, but about two years ago we started heading toward something more formal. We're not yet at the stage where there's equity or ownership – NS Power is just starting to build up its own capacity [to conduct such partnerships]."

The Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq Chiefs, representing 11 of the 13 First Nations plus two ex officio members, has a secretariat with which Nova Scotia has a five-year capacity-building agreement that is considering a couple of renewable energy projects. The provincial government has set up an Office of Aboriginal Affairs that meets regularly and provides guidance, such as on duty to consult, Mr. Toner explained.

"Nova Scotia Power is building up relationships with the Mi'kmaq communities, so that by the time duty to consult becomes a consideration, hopefully it will be a straightforward exercise," he said. "There are a host of other things we're starting to put in place. We have transmission lines across reserve lands and some of those agreements need modernization, so we're working our way through that. I think we're working well. We're coming up the inside track and we're doing much better."

New Brunswick

New Brunswick has a program for Locally Owned Renewable Energy Projects that are Small Scale (LORESS), also known as the Community Renewable Energy program. The program is regulated through the Electricity from Renewable Resources Regulation. The program allows NB Power to endeavor to obtain up to 40MW of renewable energy from Aboriginal Businesses and an additional 40MW of renewable energy from local entities as defined in the Regulation.

The program has three components:

• Procurement set-aside for Aboriginal businesses.

• Procurement set-aside for local entities, which includes, among other entities, a municipal distribution utility; a municipality, rural community or local service district; a band as defined in the Indian Act (Canada) that is located in the province; or a partnership or limited partnership between two or more bands that are located in the province.

• Procurement of electricity from renewable resources through distributed generation-owned projects without going for a competitive bid.

The LORESS program directed NB Power to issue two requests for Expressions of Interest: the first by January 31st 2016 for up to 40MW from Aboriginal businesses, and the second by January 31st 2017 for up to 40MW from local entities as defined above.

At the end of last January, Aboriginal businesses were asked to submit plans to NB Power under the Community Renewable Energy – First Nations Opportunity program, allowing for the production of 40 megawatts of electricity from renewable resources like hydro, biomass, wind and solar energy. Proposals were to be submitted by 3 p.m. on April 29. An inquiry to NB Power returned the following reply in late September: "The review and analysis of the submissions is ongoing. We expect to be able to provide all respondents to the REOI with the path forward in the near future."

Saskatchewan

SaskPower is partnering with Black Lake First Nation, with the support of the community confirmed in a November 2015 vote, to develop the Tazi Twé project (Black Lake in the Dene language), a 50 megawatt hydro development in Northern Saskatchewan. If the remaining approvals are obtained, work could start in the fall of 2017. Tazi Twé will help SaskPower meet a growing demand for power in the province’s north.

Black Lake First Nation (BLFN), through its wholly owned corporate entity (Elizabeth Falls Hydro LP) will have a 30% ownership position in a new Limited Partnership that will own the Project. SaskPower will have the remaining 70%. A November 2015 story in the Regina Leader-Post said the arrangement will provide a cash flow stream to the band for the next 90 years.

Ted De Jong, Corporate Executive Officer, Elizabeth Falls Hydro Development Corporation, explained in an email that "Black Lake First Nation spent 20 years and $8 million developing the Project before seeking an industrial partner, which in this case is SaskPower. During that period of time, BLFN undertook a prefeasibility study, full feasibility study, business plan, geological testing and preliminary engineering design work to demonstrate that the Project was commercially and technically viable and would have minimal impact on the environment.

"Only after completing all the above work, did BLFN look to an industrial partner to develop the Project, and subsequently selected SaskPower. The $8.0 million BLFN spent in developing the Project will be rolled into the new LP to satisfy a portion of Elizabeth Falls Hydro Limited Partnership (EFHLP) equity requirements. The balance of the equity will be provided by a chartered bank at very favourable interest rate, given that our Partner (SaskPower) is also the purchaser of the power."

Saskatchewan is also the first jurisdiction in North America to have a First Nation Power Authority, according to that organization's claim. On its website, FNPA says it was "established as a not-for-profit to create a landscape favorable to Aboriginal inclusion in the power sector. Created in 2011, FNPA was mandated to facilitate the development of First Nations-led power projects and promote Aboriginal participation in procurement opportunities with the crown utility in Saskatchewan, SaskPower. In order to facilitate this mandate, FNPA successfully negotiated a mutually beneficial, long-term Master Agreement with the crown utility, SaskPower. This one-of-a kind contract with a North American power utility is a 10 year agreement and provides guidance to how the FNPA and SaskPower will work together to share information and identify opportunities."

FNPA provides annual general memberships to entities wholly-owned by First Nations, including economic development corporations, bands and tribal councils. General members have direct access to FNPA support and must be the lead project proponent. The FNPA also meets and develops connections within the power industry, to assist in finding development partners. Currently, the organization lists 18 general members, as well as 49 industry members, including well-known companies like Bullfrog Power, Canadian Solar, GE Energy, Samsung C&T and Valard Construction.

While not having its own investment fund, FNPA can assist with project financing by the development of investment-ready financial models and through its network of investment resources.

Alberta

Alberta is of course, like Ontario, a market-run power system. Research for this article did not to turn up any governmental support for projects of the size described above. But on October 6 the Alberta government announced an Indigenous Solar Program (AISP) and an Alberta Indigenous Community Energy Program (AICEP) that will provide $2.5 million for First Nations and Métis Settlements to undertake renewable energy projects and energy efficiency audits in their communities. The AISP will provide grants of up to $200,000 per project to First Nations, Métis settlements and Indigenous organizations. The money will be used to install solar panels on buildings owned by communities or organizations, such as offices, medical centres, schools and more. The AICEP will help First Nations and Métis Settlements reduce emissions and save on energy costs through community energy audits funded to a maximum of $90,000.

The government said the pilot programs will also inform engagement on future climate leadership programming. In addition, the province will work with successful applicants to develop educational programs that will work as a scientific learning tool for students and community members.

In addition, IPPSO FACTO has reported in the past on a couple of private partnerships:

• Green energy provider Bullfrog Power and Montana First Nation, along with partners Green Arrow and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, announced a partnership to construct a new solar installation to reduce the financial and environmental costs of dependence on fossil fuel-based electricity generation (IPPSO FACTO, September 2015).

• Alberta-based Focus Equities Inc. and the Paul First Nation announced February 4 that they had formally advised the Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO) of their intent to proceed with and connect the proposed 1,000 MW Great Spirit Power Project to the Alberta grid. The Paul First Nation and Focus Equities signed a Memorandum of Understanding in November 2013 to jointly develop this project on the Paul First Nation's traditional territories (IPPSO FACTO, April 2014).

British Columbia

The dominant news from British Columbia has of course been about the massive Site C on the Peace River in the northeast of the province. The project has become a focus of controversy. Two communities from Treaty 8 territory, Prophet River and West Moberly, have so far gone as high as the Federal Court of Appeal saying the project violates their constitutionally protected treaty rights. Assembly of First Nations Grand Chief Perry Bellegarde has said, “First Nations have inherent rights and sacred responsibilities to our traditional territories and these rights and responsibilities must be respected and upheld by all governments. The Site C dam project threatens to flood thousands of acres in Treaty 8 territory. This is a violation of First Nations’ inherent and Treaty rights. The standard of free, prior and informed consent in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples must be upheld.”

On the other hand, the Dene Tha' First Nation and BC McLeod Lake Indian Band have reached agreements with BC Hydro on the project over economic development opportunities and other benefits. For its part, BC Hydro says, "Offers of accommodation have been made to all of the First Nations significantly affected by Site C and BC Hydro is committed to working hard with Aboriginal groups to address their concerns and identify opportunities for them to benefit."

IPPSO FACTO has been unable to learn of any programs under the BC government or BC Hydro to encourage partnership of First Nations in energy development projects, but several private companies have stepped up to partner with local Aboriginal communities. A recent one is BluEarth Renewables, which has partnered with the Sechelt Nation in the 33 MW Narrows Inlet hydro project, about 75 kilometres northwest of Vancouver Tzoonie River valley.

IPPSO FACTO has also reported on several developments in the last couple of years, in First Nation-private company partnerships:

• Innergex and Cayoose Creek Development Corporation, the economic arm of the Cayoose Creek Indian Band, having formed the Cayoose Creek Limited Partnership, announced the acquisition February 25 of the Walden North hydroelectric facility in BC (April 2016).

• Pattern Energy Group LP announced the completion of $393 million in financing of its 180 megawatt Meikle Wind power project. Design and planning for the project, the largest wind power project in British Columbia, incorporated input from First Nations, the Tumbler Ridge and Chetwynd communities, and the provincial government. It was expected to commence commercial operation in late 2016 (September 2015).

• The Winchie Creek Hydro project, a latest run-of-river hydro development by the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation on Vancouver Island, is the third run-of-river facility undertaken by the community. The first, Canoe Creek Hydro, has been in operation since 2010. The second facility, Haa-ak-suuk Creek Hydro, is nearing completion. Funding was provided by the federal Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development (November 2014).

• Innergex Renewable Energy Inc. and the In-shuck-ch Nation announced the joint signing August 12 of a 50-50 partnership to develop six run-of-river hydro projects, totaling approximately 150 MW, spread between six creeks located within the First Nation’s traditional territories: Rogers Creek, Snowcap Creek, Gowan Creek, Kakila Creek, Tuwasus Creek and Billygoat Creek (November 2014).

• Shíshálh Nation Chief Garry Feschuk announced the signing of an agreement January 31 between the First Nation and the Western Tidal company. The two organizations will co-operate to investigate the feasibility of a tidal power project in Agamemnon Channel, on the coast of British Columbia. The Nation and Western Tidal will jointly decide, after due diligence, if the project will proceed to the development stage (April 2014).

See also IPPSO FACTO, February 2015: First Nation challenges to hydroelectric development – A tale of two provinces: "BC and Ontario have followed two different paths, after the impacts of major hydro developments in the 1960s led to anger among First Nations, followed by substantial settlement payments. Subsequently, BC has engaged with First Nations, but as part of a Joint Review process, while Ontario has followed a co-planning route."