By Stephen Kishewitsch and Jake Brooks

It’s different this time.

The widely-publicized international agreement on climate change last December in Paris turned out to be a watershed moment in international governance, and one that will likely cause significant movement in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Participants and analysts seem to agree that the nature of the accord was unlike any before: more serious, more impactful, and better suited to current conditions.

“Truly historic,” is how Lisa DeMarco of DeMarco Allan LLP describes the event, known formally as COP21, the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Aside from being the largest gathering ever of national heads of state, by the end of the meeting 188 out of the 196 nations represented had submitted emission reduction targets (INDCs, Intended Nationally Determined Contributions). These INDCs are not enforced by international bodies directly, but they represent a new “bottom-up” strategy for achieving international targets that is more practical to negotiate and manage.

Ms DeMarco, who took part in the Paris conference as well as several of its predecessors, cites several reasons to believe the latest conference will make a difference. Speaking to a Mindfirst seminar in Toronto on January 22, she noted that for the first time there was an inclusive approach resulting in real ambition, an express provision for market instruments, and a transparency framework that was agreed upon by all, to prevent double-counting. Although COP21 took a relatively light-handed approach to compliance, this was arguably unavoidable because of what was required to avoid the necessity of US Senate ratification. Instead, at COP21 it became clear that the preferred implementation approach is INDCs, in combination with the start of multi-nation “carbon clubs” with their own reciprocity and compliance rules that could have trade implications. “COP 21 took essentially a bottom-up, rather than top-down approach,” DeMarco stressed, a strategy that is likely to be able to endure through a variety of changes over time. “There is room for additional ambition, enforcement and public pressure,” she said.

The conference in total included some 40,000 attendees scattered around various venues, of whom “only” 500 were official negotiators.

The agreed-upon international GHG objective is limiting emissions by 2030 to a level that would produce a global average temperature increase of no more than two degrees Celsius above the historical baseline, which is widely agreed to be the maximum temperature rise in order to avoid increasingly unrecognizable and destructive weather patterns and related significant consequences. ... In fact, more recent modeling, endorsed by the fifth and most recent Assessment Report from the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change, calls for that critical maximum temperature increase to be set lower, at 1.5 degrees, which was recognized in the Paris Agreement.

That said, the heavy lifting is still ahead, DeMarco stressed. The Paris agreement requires Parties to submit targets, and to renew them more stringently every five years. The specific modalities required to implement the Paris Agreement will need to be negotiated over the next several COP meetings. Enforcement of compliance in meeting the targets is largely left to the mechanisms each nation sets up internally. In the case of the United States, for example, enforcement for the power sector will be, in part, through the recently finalized Clean Power Plan, which is overseen by the EPA. The only international enforcement mechanisms available to penalize non-conformance are to be found around the edges, in the form of things like carbon clubs that can lead to trade-related pressures to comply. However, as DeMarco put it, now “at least we have baby teeth.”

See "Paris: Key outcomes," below, for a summary of the major aspects of the Paris agreement.

A couple of factors worth noting:

• To date, subnational actors – provinces, States like California south of the border, individual cities, and businesses and industrial sectors – have played a significant role in implementing programs and achieving emission reductions. Moreover, that’s likely to continue to be the case, at least in North America. Panel member Alex Wood, Executive Director in the Ontario Climate Change Directorate, observed that in a continent with widely varying regional economies, national governments have a perhaps politically insurmountable task in trying to devise and, even more so, impose one policy for everyone. It’s been up to each province to craft a system that works for them – and in the process, demonstrate that the anticipated harmful results have not shown up. Then, once there is an effective international agreement, some kind of overlay can be stitched together nationally to represent the country. Wood admits that reaching the agreement in principle will be a good deal easier than arriving at an interprovincial burden-sharing agreement. However it seems that this is the only way it can be done, at least in Canada and quite possibly elsewhere.

A similar point is made by Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission. With a federal-provincial ministerial meeting scheduled for March to discuss the details of a national approach to GHG reduction, the commission has begun a series of blogs on the subject. Two points are stressed up front: any system the ministers come up with will have to harness the power of markets by employing carbon pricing as its centrepiece, and the provinces have a significant role in the development of policies.

At the Paris conference, provincial participation was recognized as an active and important contribution to the production of a workable agreement that everyone could sign on to.

The blog can be read at ecofiscal.ca, under Latest Blog Posts (see “The Many Pieces of Canada’s Federal-Provincial Climate Puzzle,” January 27).

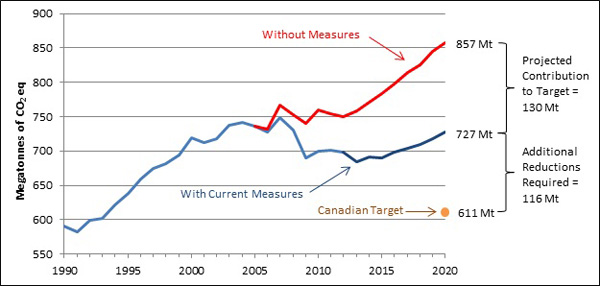

• What it means for Canada: The Canadian government, since the election of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has indicated that it will examine the previous government’s target of an emissions reduction of 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. There are doubts as to whether policies in place are sufficient to reach the goal. An Environment Canada projection in 2014 foresaw a gap by 2020 (see graph).

• What it means for Canada: The Canadian government, since the election of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has indicated that it will examine the previous government’s target of an emissions reduction of 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. There are doubts as to whether policies in place are sufficient to reach the goal. An Environment Canada projection in 2014 foresaw a gap by 2020 (see graph).

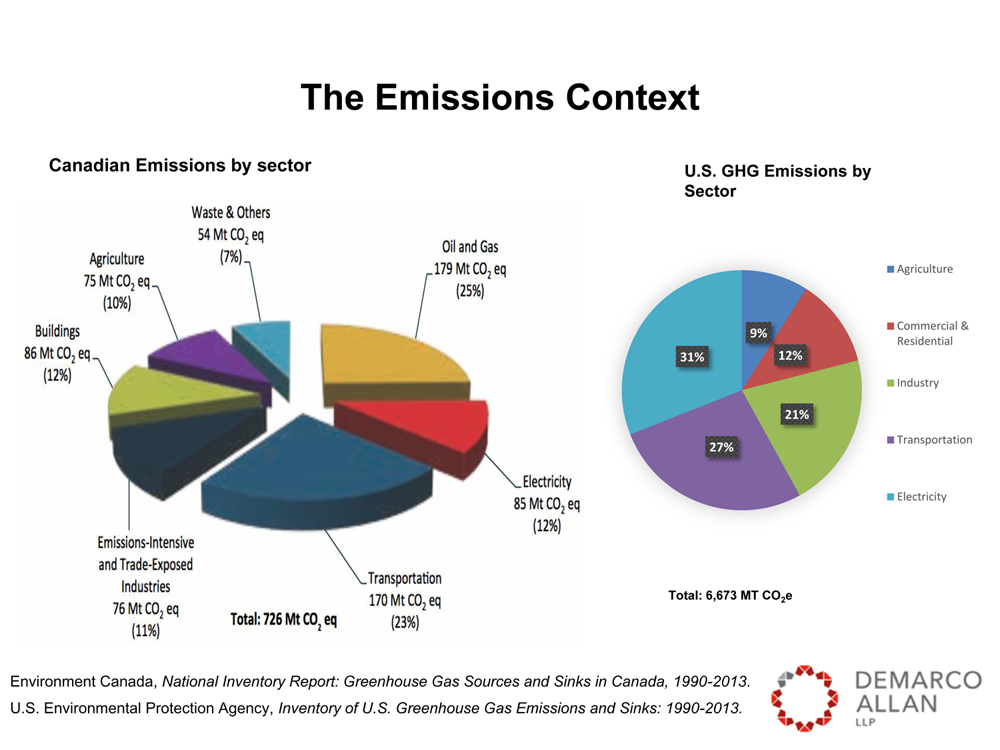

But unlike the US, Canada will have to look elsewhere than the electricity sector for those reductions; notably, oil and gas, refining, buildings, industrial, and the transportation sectors. Ontario has already undertaken the continent’s largest single emissions reduction action, in closing the coal-fired plants. There is very little coal-fired power generation that remains in Canada. Most of the rest of the country’s electricity comes from zero-emission hydro and nuclear power, with a small amount of limited gas–fired power generation The vast majority of electricity generated in Canada is generated by a small number of large operators, and is therefore relatively easier to regulate. However, many of the emission reductions from Canada’s power sector have already been made and the country has one of the lowest emission intensity electricity grids in the world. The remaining dominant emitting sectors may prove much more challenging to regulate. Time will tell in both Ontario and federally, as each government is scheduled to release more detailed plans this year.

But unlike the US, Canada will have to look elsewhere than the electricity sector for those reductions; notably, oil and gas, refining, buildings, industrial, and the transportation sectors. Ontario has already undertaken the continent’s largest single emissions reduction action, in closing the coal-fired plants. There is very little coal-fired power generation that remains in Canada. Most of the rest of the country’s electricity comes from zero-emission hydro and nuclear power, with a small amount of limited gas–fired power generation The vast majority of electricity generated in Canada is generated by a small number of large operators, and is therefore relatively easier to regulate. However, many of the emission reductions from Canada’s power sector have already been made and the country has one of the lowest emission intensity electricity grids in the world. The remaining dominant emitting sectors may prove much more challenging to regulate. Time will tell in both Ontario and federally, as each government is scheduled to release more detailed plans this year.

Outside of COP21 there were commitments to finance hundreds of billions of carbon reduction initiatives privately. Anthony D’Agostino, Director of Emissions Markets at RBC, said that the year 2015 saw a series of extremely positive actions on climate change, and called the Paris treaty, “the most ambitious climate change agreement in history.”

By the time of the Mindfirst seminar on January 22, the number of countries who had submitted INDCs had grown to 192, and all 196 are expected to have submitted an INDC before or soon after the Paris Agreement is open for ratification on April 22, 2016.

Paris: Key outcomes

The agreement is more ambitious than ever before

• The goal is a global temperature increase “well below 2°C” with “efforts to limit … to 1.5°C”

• A global gap remains between current projections and the end state consistent with the 2 degree target. Annual global emissions are currently projected to be 55 gigatonnes (GT) of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030, but, according to the models, emissions will need to be down to 40 GT to keep the increase to 2°C or less.

• More groups are included. Where formerly only state-level actors were counted, now the agreement covers indigenous peoples, human rights, all levels of government, “various actors” (private sector, Article 6)

Mitigation

• All countries shall submit successive, 5-year, increasingly ambitious intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) intended to achieve reductions.

Markets

• Full article cooperative approaches among countries, no double counting, new mechanism

• Non-market approaches for states like Venezuela.

• Forest and other sinks.

Loss and Damage and Adaptation for more vulnerable countries.

Finance

• Inside COP – Floor of $100 B/year ($2.65 billion from Canada over 5 years + earmark for adaptation). Green climate fund.

• Outside COP – Mission Innovation, CPLC, World Bank 100/100/100, BAML, Credit Agricole, and more. $300 billion have been committed or mobilized, by the likes of Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Mark Zuckerberg. Credit facilities have been made available to support R&D through to deployment.

Tech Transfer and Capacity Building

Transparency and Accounting

• Transparency frameworks for action and support (money) that works for everyone; good no double counting.

Global stocktaking and review

• A key provision – 2023 and every 5 years, will inform new INDCs (targets). Information going back and forth between science.

Compliance

• Development of carbon clubs that can lead to trade-related compliance.

Signature and coming into force

• The agreement will be open for signature on Earth Day, April 22, 2016, for a year.

• It will come into force with the signature of 55 of the parties, representing 55% of global emissions. This is a lower threshold than Kyoto, and may well be reached before 2020.

The legal form is stronger than anything we’ve seen up to now. The first stocktaking will be in 2018; then the market provisions should be well in play After that every 5 years new targets are to be set.

• There is a strong presumption that existing markets will be rolled into new mechanisms. The clean development mechanism (CDM), etc., will no longer exist.

• Annex to COP decision, INDCs separate repository.

• 6 official UN languages of equal force.

Summary courtesy Elisabeth DeMarco, DeMarco Allan LLP.