By Stephen Kishewitsch

The City of Toronto is facing an energy crunch tougher than that of any other city in Canada. The city is responding with a mix of policies, programs, and projects likely to break ground in several areas, both to attract private interest and investment and to lead by example with its own strategic investments. The primary focus is not on technology, but on innovative solutions to urban energy problems. Although its basic energy issues are similar to those of other fast-growing municipalities, few have the multi-faceted challenge of massive growth, concentrated development, limited inbound supply capacity, aging infrastructure and adapting to a changing climate to the extent that Toronto does.

The City of Toronto is facing an energy crunch tougher than that of any other city in Canada. The city is responding with a mix of policies, programs, and projects likely to break ground in several areas, both to attract private interest and investment and to lead by example with its own strategic investments. The primary focus is not on technology, but on innovative solutions to urban energy problems. Although its basic energy issues are similar to those of other fast-growing municipalities, few have the multi-faceted challenge of massive growth, concentrated development, limited inbound supply capacity, aging infrastructure and adapting to a changing climate to the extent that Toronto does.

The fundamental issues are well-known and well-understood. Thanks to its size, its function as a magnet for immigrants, and the reversal of a decades-long pattern of sprawl into one of densification, Toronto can expect to be among the first in Canada to face a number of challenges. It will also likely be the first to try out major innovations that could lead the way for others.

The challenges, in a bit of detail:

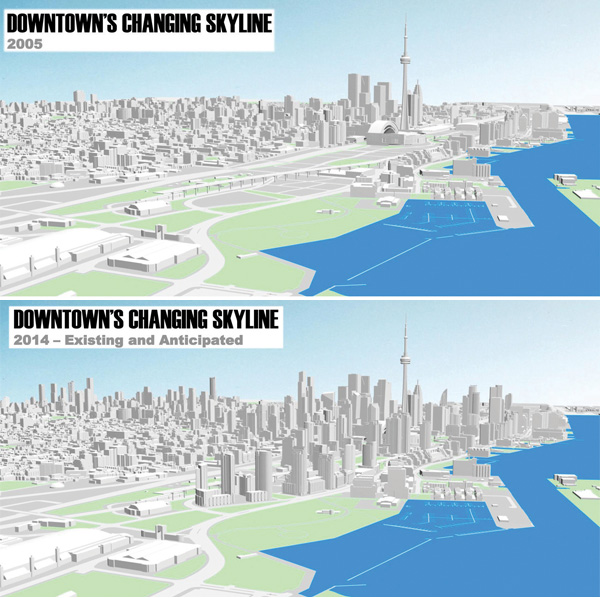

• Growth: By 2031 Toronto proper is projected to have 4 million people, rising to 6 million by 2041. The Greater Toronto Area has more than 6 million already but the challenges within the formal City boundaries are unique. As the city’s energy plan observes, over 50,000 condominium units have been added south of Bloor Street since 2000 and the city has the most high-rise buildings under construction in North America. Approximately 160 cranes are at work, and have been for a few years. In particular, Toronto is growing vertically – development is occurring predominantly through intensification of built-up areas.

Perhaps unexpectedly, even with rapid population growth and urban intensification, Toronto as a whole is expected to see a 4 percent reduction in total electricity consumption between 2009 and 2019. However, while electricity consumption overall is expected to decline, the amount of power consumed during times of peak demand – typically hot summer days and cold winter nights – is expected to continue to increase. In Toronto, peak electricity demand is expected to rise by just over 1% a year until 2019. In particular, industry, which has a relatively flat load profile, is leaving Toronto, while the high-rise condos represent increasing demand.

Perhaps unexpectedly, even with rapid population growth and urban intensification, Toronto as a whole is expected to see a 4 percent reduction in total electricity consumption between 2009 and 2019. However, while electricity consumption overall is expected to decline, the amount of power consumed during times of peak demand – typically hot summer days and cold winter nights – is expected to continue to increase. In Toronto, peak electricity demand is expected to rise by just over 1% a year until 2019. In particular, industry, which has a relatively flat load profile, is leaving Toronto, while the high-rise condos represent increasing demand.

Downtown in particular, with the densest population, is also growing four times as fast as the rest of the city. A single building, like One Bloor East, currently nearing its final height of 76 storeys and 789 units, or One Bloor West, planned for 80 storeys, will each add a small town’s worth of population and demand at a single intersection. The current model for the two-tower Mirvish and Gehry project on King Street strives higher still, at 82 and 90 storeys. Somehow, these megaliths must be assured of having all their services in place when people move in – notably water and electricity, including the electricity needed to pump that water to the top floor. Power for treating and pumping water is the city’s largest single source of demand.

How is the city going to manage that? A crucial question for urban planners.

• Dealing with the impacts of climate change. An increasing demand for power to supply air conditioning in ever warmer summers is an obvious issue. Notably however, total electricity consumption is projected to be flat or even decline for the next few years, except for certain hot spots. Managing peak demand is clearly the central challenge, in both summer and winter. Probably more critical still is an expected increase in extreme weather events, incidents that can flood transformer vaults, blow up transformers in summer heat or tear ice-covered lines from electricity poles in winter.

For the downtown core there are two main transmission supply points, Leaside and Manby. If an extreme weather event does take out one of these sources (a rare event), how are people on the 90th floor to leave or get home? The 2013 summer flood and winter ice storm between them left one million residents without power for days. The Ontario Building Code does not yet have minimum back-up power requirements for high-rise buildings in case of grid failure, only emergency power to evacuate the building in case of fire.

• The need for a system resilient enough to keep at least critical services – water treatment plants, hospitals, police stations, public transit, and community centres running during an emergency.

• Limitations on energy supply. Transmission capacity into downtown is essentially fixed, though in the horseshoe around the city core there are additional supply points, that, with some load switching at the substations, can bring power further into the city. Meanwhile development hot spots in the downtown and the west of the city mean increasing demand.

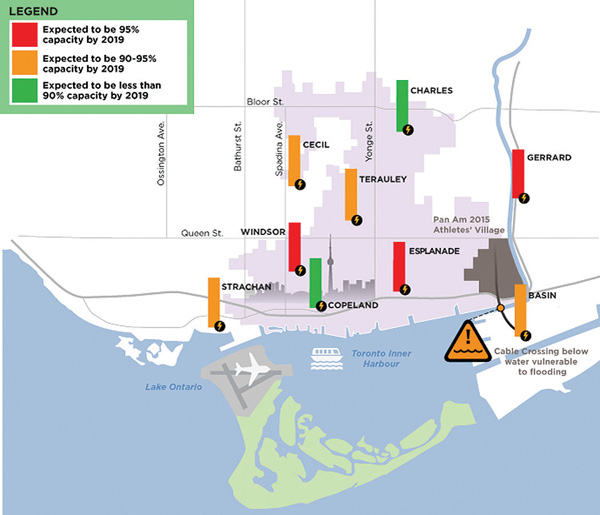

• Replacing aging equipment, while at the same time preparing for more demanding conditions. A significant proportion of Toronto’s lines and transformer stations are at or near their design limit – and that’s for normal peak conditions. Extra preparation will be needed for extreme conditions. Toronto Hydro’s projections see 80% of downtown transformer station reaching capacity by 2019 (see map).

• Replacing aging equipment, while at the same time preparing for more demanding conditions. A significant proportion of Toronto’s lines and transformer stations are at or near their design limit – and that’s for normal peak conditions. Extra preparation will be needed for extreme conditions. Toronto Hydro’s projections see 80% of downtown transformer station reaching capacity by 2019 (see map).

• The risk of revenue loss for utilities like Toronto Hydro is a potential concern for many, as customers may increasingly opt to generate some of their own power – typically rooftop solar on the part of residential customers, as the price of photovoltaics continues to fall; or cogeneration facilities on the part of commercial customers who can use process heat in addition to the security of generating some of their own power. In one scenario, the power utility can experience challenges if enough customers leave the system and infrastructure costs for rebuilding an aging system are passed along to a shrinking customer base. See the sidebar, “Revenue loss – a dilemma or not?” page 28.

Fernando Carou, lead energy planner in Toronto’s Environment and Energy Division, described the case well in a presentation at the Mowat Centre in September 2013 that was part of the Ontario Long Term Energy Plan consultations: Traditionally land-use planning and energy planning have been in completely separate silos. The city would put in roads and water, and the central utility would put in the wires. The traditional approach relied on large central electrical infrastructure with long lead times, 100% public-funded. Power supply and delivery infrastructure would be overbuilt, so that there was excess capacity to grow into over time. Relying on large facilities has come to mean facing public opposition. After Ontario Hydro was broken up into several entities, the many players involved in large electricity delivery (IESO/HONI/LDCs/OEB/the Ministry of Energy) make planning and coordination and accountability quite complicated.

“When sprawl was the dominant growth mode for 50 – 60 years, this division of labour was okay,” he comments. “The infrastructure would go in, then developers would put the buildings on top, and move on. But now, growth is vertical, and that can’t work any more. You can’t direct the additional population to a new greenfield development where new infrastructure is waiting to take up the load – the new customers with their additional load are right on top of the existing systems.”

A September 16, 2013 letter from the city’s Chief Corporate Officer, Josie Scioli, to the Ministry of Energy said, “The traditional approach of large central energy supply has a lead time that is well beyond the critical growth period. ... The current provincial energy plan has a bias toward large, electricity only, rate-base funded solutions. Growing communities will be better served by small-scale, integrated energy solutions that address energy load growth at the source – embedded solutions. ... A bias towards traditional large scale electricity infrastructure requires the province to provide, secure or approve the capital required for implementation. In contrast, embedded energy solutions ... only require policy or procedural changes or enabling legislation to make it happen.”

The City of Toronto’s Environment and Energy Division is planning for and delivering on a new approach, “embedded energy solutions,” with the following key characteristics:

• Conservation first from high performance buildings, such as thermal networks with behind-the-meter supply close to load, integrated in new development and reaching out to existing developments

• Staged investment, growing organically

• Avoid or defer new large scale electrical transmission or generation

• Improved energy security by virtue of a diverse local supply – “multiple eggs in multiple baskets”

• Local energy solutions that integrate well with buildings and dense urban form

• Tailoring: being small, embedded energy solutions attract private investment, with solutions driven by the energy developer and real estate developer’s business case

• Thermal efficiency: being local, embedded energy solutions can also recover heat to supply local heat requirements through combined heat and power (and cooling, with tri-generation).

• Short lead times, versus a decade or more for large energy projects

• Public acceptance strengths - NIMBY to PIMBY (sure, go ahead and Put It in My Back Yard). Rob McMonagle, Senior Advisor – Green Economy at the City’s Economic Development and Culture Division offers an example from Germany of a local DE CHP system that was built small enough that it could be surrounded by townhouses and a child care centre. “No-one objects to having a furnace, everyone has one. Do a small central furnace instead of ten individual ones. But it has to be done respectfully, and it can’t stand out.”

• More autonomy.

None of this requires new technology, Carou points out. Accessible examples can already be found in hospitals and campuses. Solutions driven by criteria like the above not only reduce pressure on the grid, he argues, they reduce pressure on the rate base, at the same time as reducing social friction related to energy infrastructure.

Incremental or structural change?

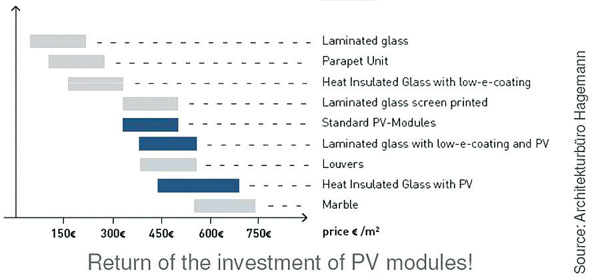

It may be a matter of emphasis, but the new approach described above suggests a picture of the future city that feels different from today. Rooftops in the inner suburbs are peppered with photovoltaics, and the condo towers downtown have PV built into the cladding. Cogeneration or tri-generation provides neighbourhood-scale district energy. Flywheels or battery banks or electric cars provide grid support, local resiliency and peak power, while conventional central power fills in the rest and provides backup – something like where the northern European cities seem to be going.

Looking at the picture from a different angle we may see much the same city as today. It has a denser population living in more towers, but is still essentially reliant on power brought in from outside, though increasingly by new and improved wires and transformers, and complemented strategically by local resources as a second tier of infrastructure that will keep hospitals and other essential centres operating the next time the weather strikes hard.

Should the guardians of the system be looking toward a tipping point where one style of system takes over, or will the incremental day-to-day decisions take care of the needed changes by themselves?

The classic science fiction picture of the city of the future is pretty universally a scene of gleaming silver towers soaring to the sky. Some are already here, and more are definitely on the way. How familiar will the system be underneath?

Toward a plan

Fernando Carou states the case unequivocally from the city’s perspective: the old growth model is done.

“The increasing demand for electrons in an increasingly dense urban setting has come up against a finite existing supply – just like the demand for roads. We’re not building any more roads. Capacity is not magically going to increase, that’s not my job. Rather, it’s about how we can get more out of the existing system, by shifting demand within existing capacity. The last thing we want is for energy to become a bottleneck for growth or prosperity or social justice. That means resilience and reliability. We, as the city, represent the interest of the public, as well as being large energy users ourselves. We’re trying to make smart decisions on the demand side, and introduce a multitude of behind-the-meter small generation, integrated into buildings, that looks like the demand side. Over time, we can shift to sourcing 30% of electrical demand in Toronto from behind the meter local efficient generation, together with peak shaving and conservation.

In pursuit of that, for example, the city has set its own green development standard. A developer can’t build in Toronto today unless their design is 15% more efficient than code. Smart builders today are going for 25% more efficient than code, in return for which they get a 20% rebate on development charges.

“We’re looking for solutions that can address more than one challenge,” Carou continues. It means a paradigm shift from central to decentralized, taking advantage of the efficiency of CHP and thermal networks. We want to spread behind-the-meter generation around, integrate it into the urban fabric. There’s no space any more, and land is too valuable, for large footprint installations. There’s no place to put in another transmission line close to downtown. We want to see power decentralized, at the neighbourhood, block, and individual development scales.”

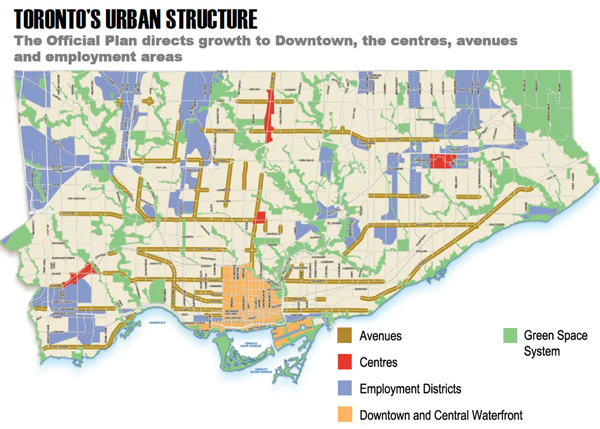

The community energy plans for Scarborough, Etobicoke and Mimico all involve about a hundred high-rise buildings. The plan for downtown Toronto involves 8300 buildings. That’s the largest of several local area plans, four of which have been completed under a city-wide top-level sustainable energy plan.

The community energy plans for Scarborough, Etobicoke and Mimico all involve about a hundred high-rise buildings. The plan for downtown Toronto involves 8300 buildings. That’s the largest of several local area plans, four of which have been completed under a city-wide top-level sustainable energy plan.

Implementation has 3 parts, Carou explains:

• Setting policy. The guidelines and minimum standards come first. The city is preparing a workshop for the fall, for example, on minimum standards for power backup, primarily multi-residential. Changes are coming in the fall to the official plan, with new requirements taking effect in 2016. Developers will have to be able to say how they’re going to meet the minimum standards for building power. In line with the principle that the new vision will be driven by business decisions, the Environment and Energy Division works with developers on costed-out business cases.

• Capacity building: developing a more comprehensive working interface with energy developers, real estate developers, property managers and owners, and utilities and planners (IESO) as stakeholders in energy planning – becoming able to integrate energy considerations into the traditional silos of water and public buildings. “The leading developers are starting to see that, as a business proposition, resiliency to grid failure, conservation, efficiency, predictable power cost are increasingly important in the value of their buildings and branding for their companies.

“The city isn’t trying to provide the needed infrastructure by dangling money in front of developers, the city is creating a framework and building capacity by engaging with industry to affect the conventional outlook. Currently, we’re working with leading developers that are internally motivated to face the energy challenge, as well as seize business and reputational opportunity.

“There will be a time for incentives and a time for requirements, but first you want to work with willing parties on solutions that are financially viable today. Then implement and accelerate to get scale and have an impact. In 2-3 years, much like we have a framework for real estate developers to invest and build buildings, we’ll have a framework for energy developers to invest and build embedded energy solutions close to load that integrate well with the dense urban form.”

• And finally, some characteristic individual projects.

What’s being done now? Some energy projects underway.

• LEED buildings. Developers in Toronto must meet the city’s Green Building Standard, which stipulates a building energy efficiency at least 15% better than code in energy efficiency. Developers who achieve a 25% improvement code receive a rebate on their development costs. On average, 8% of all new buildings are now “green,” with more new green buildings than any other city in North America.

Toronto has several policies and programs to help build Toronto’s green building industry, including:

Toronto has several policies and programs to help build Toronto’s green building industry, including:

• Toronto Green Standard

• Green Roof Bylaw

• Toronto Renewable Energy Bylaw

• Bird Friendly Development Guidelines

• Tower Renewal

• Eco-Roof Incentive Program

• Better Building Partnership

• The City’s Economic Development and Culture Division is working with the Greater Toronto Chapter of the Canada Green Building Council (CaGBC-GTC) is working advance the adoption of building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV).

More information is available at http://www.cagbctoronto.org/initiatives/building-integrated-photovoltaic-bipv-industry-development-initiative.

• The Toronto Atmospheric Fund has created an investment corporation to fund building efficiency. See “New financing company set to invest $100M,” page 14.

• The City’s renewable energy office has by now installed over a megawatt of rooftop photovoltaics on its own properties, and growing. It is also looking at other energy sources at its facilities, including geo-exchange and CHP using waste wood from management of the city’s trees, waste that currently goes to landfill.

• The City has identified 27 nodes, three of them a priority – growth centres, at major intersections, where natural gas can be used efficiently – DE systems, load displacement, e.g. on campuses and recreational facilities. See map above. Existing district energy systems and combined heat and power are marked in orange, potential new nodes are in yellow. There are some 60 indoor pools in Toronto that can use 100 kW of CHP. Development of the energy facilities would be business-case driven; no dollars required from the rate base.

• The City has identified 27 nodes, three of them a priority – growth centres, at major intersections, where natural gas can be used efficiently – DE systems, load displacement, e.g. on campuses and recreational facilities. See map above. Existing district energy systems and combined heat and power are marked in orange, potential new nodes are in yellow. There are some 60 indoor pools in Toronto that can use 100 kW of CHP. Development of the energy facilities would be business-case driven; no dollars required from the rate base.

A new district energy centre is under construction in Exhibition place. Phase 1 will connect existing energy assets (including a 1.6 MW CHP) to supply heating and cooling to the New X Hotel under construction there (to open in Spring 2016) under a long-term energy purchase agreement. The facility will provide new net revenue for Exhibition Place and the City, and benefits to the hotel developer.

A new district energy centre is under construction in Exhibition place. Phase 1 will connect existing energy assets (including a 1.6 MW CHP) to supply heating and cooling to the New X Hotel under construction there (to open in Spring 2016) under a long-term energy purchase agreement. The facility will provide new net revenue for Exhibition Place and the City, and benefits to the hotel developer.

• The city released a request for qualifications (RFQ), closing July 31, for CHP in two community centres with aquatic facilities. The CHP will provide day-to-day energy management, and backup power to allow the centres to act as reception centres for residents during an emergency area-wide power outage/grid failure.

• The city has a 2 megawatt CHP project at its Disco Road solid waste, source separated organics facility for Green Bin collection processing. It’s been enrolled in the IESO’s PSUI program for engineering feasibility, but may be better suited for the upcoming CCHP incentive program under the save-on-energy banner from Toronto Hydro.

• Westwood Theatre Lands in the Etobicoke-Lakeshore area, also known as the Spaghetti Junction, are a brownfield the City owns and plans to redevelop for three million square feet of mixed use. District energy piping has been going in to connect the various development parcels. Inside Toronto reported in January 2013 that the YMCA has been looking at building a centre there.

• Toronto Hydro Energy Services Inc. is proposing a biogas cogeneration plant to be located adjacent to the Ashbridges Bay Treatment Plant on the lakeshore east of downtown. The facility will utilize biogas produced in existing digesters at the treatment plant to generate 9.9 MW of electricity, using seven reciprocating engine gensets, as well as hot water, under the IESO’s Process and Systems Upgrade Initiative (PSUI). The treatment will use the hot water for process heat. Toronto Hydro Energy has entered into a long term lease agreement with the City of Toronto for the site location.

• It’s not an energy centre, but Sherbourne Common, a stormwater treatment facility that is also a park, is a showcase of how to design an attractive facility so it’s integrated into and accepted by a community.

• It’s not an energy centre, but Sherbourne Common, a stormwater treatment facility that is also a park, is a showcase of how to design an attractive facility so it’s integrated into and accepted by a community.

• Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) has released a Request for Proposals for a CHP system for the 3000 resident housing complex at Moss Park. Electrical capacity is to be 1 MW, and 1.2 MW worth of hot water. A GeoExchange system is also part of the RFP, for summer heat dissipation and winter heating. The RFP closed on July 15.

In December TCHC also announced a plan to replace aging emergency generators in hundreds of its buildings across the city. Under the 2015 capital plan, TCHC says 20 buildings will receive new natural gas generators to help residents comfortably stay in their homes during prolonged power outages. If it receives the funding it is seeking from the federal and provincial governments to continue its capital repair program, more than 180 aging emergency generators in buildings across the city will be replaced in the coming few years.

A representative of Toronto Community Housing Corporation said TCHC is also evaluating the feasibility and business case of constructing a CHP unit in Regent Park, but no decision has been taken as yet.

• Enwave, which operates a district heating and cooling network in downtown Toronto, has been awarded a contract by the IESO to design, install and operate a 3.85 MW combined heat and power plant at its Pearl Street Steam Plant location. The system will export 100% of the net power generated to Toronto Hydro’s electrical distribution system while recovering the available heat to increase the availability of steam generated by the plant, supplying Enwave’s customers.

Enwave is believed to be interested in significantly expanding its deep lake water cooling. Enwave, founded as the Deep Lake Water Cooling system in Toronto, was purchased by Brookfield Asset Management Inc. in 2012, and Enwave USA is now a national energy technology brand in the United States.

• The city’s Strategic Sectors Growth Office, where McMonagle is lead on the green sector, is working with Cleantech Scandinavia on an international cleantech cities initiative. The focus is for cities to work with local innovators that need assistance demonstrating innovations in green infrastructure.

See the side story, “Does the plan do what it needs to do? ”

See also “Revenue loss – a dilemma or not? ”

See also “The energy of cities: Power systems as a defining part of urban development ,” IPPSO FACTO, April 2012.