By Jake Brooks

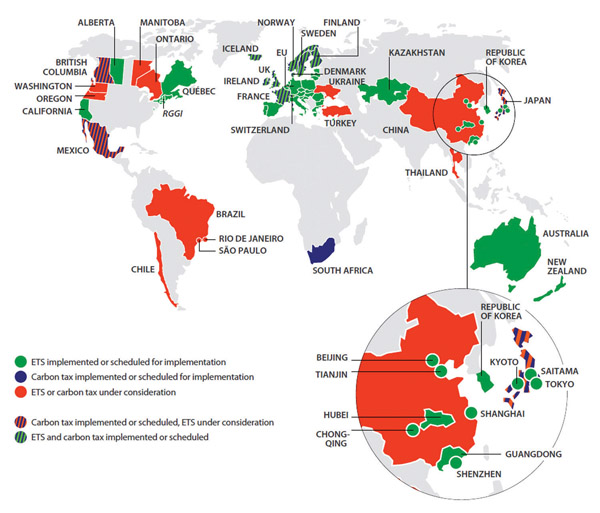

With its announcement on April 13 the Government of Ontario has arguably set the primary direction for mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the province if not the country for the foreseeable future. Confirming that Ontario will move to adopt a cap-and-trade system, Premier Kathleen Wynne said, “Climate change needs to be fought around the globe, and it needs to be fought here in Canada and Ontario. The action we are taking today will help secure a healthier environment, a more competitive economy and a better future for our children and grandchildren.” Although the specifics of how the rules will operate in Ontario are yet to be determined, the government has indicated that it will conform to the framework established by the Western Climate Initiative (WCI) an international system that already has the support of Quebec, British Columbia, Manitoba, and the state of California.

In addition to establishing fixed emission limits, the cap-and-trade approach to emission regulation is widely seen as a method of putting a price on carbon. In its official statements, the province noted that “With Ontario’s introduction of a cap and trade system, more than 75 per cent of Canadians will live in a province with some form of carbon pricing.”

A variety of stakeholders praised the government’s announcement as an important clarification of direction and confirmation of intentions. For example, Merran Smith, Director, Clean Energy Canada, said, that, “Carbon pricing is rapidly emerging as ‘the new normal’ – close to half of the world’s GDP is already covered by some form of emissions price. We’re thrilled Ontario has joined this growing league of global leaders.”

Even some of the major emitters of carbon expressed praise for the decision. Michael McSweeney, President and CEO of the Cement Association of Canada, said, “Our environment -- and our economy -- needs a price on carbon. A well-designed cap and trade system that is sensitive to trade related competitiveness issues will guarantee emissions reductions while sending a signal to the market that rewards good environmental behaviour. Further, by reinvesting cap-and-trade proceeds in resilient low-carbon infrastructure and innovation, Ontario can reduce greenhouse gases while supporting a more robust and competitive provincial economy.” Support was also voiced by such industry leaders as General Motors Canada, the Automotive Parts Manufacturers Association, and Tembec.

The announcement was not unexpected, coming on the heels of a period of consultation during which the government invited public comment on a discussion paper that compared broad options. “Ambitious in tone and broad in scope” is a typical description by commentators on the Ontario government’s climate change discussion paper, released February 12. To many it read like a precursor to challenging new provincial policy initiatives to reduce GHGs in the near term. In fact, the province had been closely associated with the WCI for years, having first announced its membership in 2008.

Where other governments at other times have called for modest reductions in carbon intensity from a less demanding baseline than the original 1990 set under the Kyoto Protocol, or set targets decades into the future, Ontario’s February discussion paper made no bones about the gravity of the issue and the extent of the greenhouse gas reductions needed to mitigate it: stabilization of emissions in five to ten years, reduction by 80% by 2050, and neutralized in the second half of this century.

The discussion paper proposed ten guiding principles, and action in four critical policy areas. See sidebar for the principles.

The critical policy areas

1. Put a price on carbon

All authorities agree that any effective program of GHG emissions reduction will, one way or another, have the effect of putting a price on carbon dioxide emissions (and, at least in principle, other GHGs like methane). The paper contemplates four basic carbon pricing instruments: cap and trade, carbon tax, baseline and credit trading, and regulations and standards. With its April 13 announcement of course, the Ontario government confirmed that it has settled on a cap and trade system.

The efficiency and effectiveness of any carbon pricing mechanism is highly dependent on the specific design of the instrument. From a theoretical point of view, many economists tend to see a tax on carbon as the most straightforward: place a price on the carbon content at the mine mouth or well head, and the cost embodied in ensuing goods and services will filter throughout the economy, driving consumers and producers to make efficiencies without further need for intervention. Properly done, the tax may be revenue neutral. Kristyn Annis, a special advisor to the group Canadians for Clean Prosperity, observed in an interview for MacLean’s magazine, “It’s an opportunity to cut taxes on things we want more of, like jobs and income.”

The carbon tax approach does suffer however, from a few indisputable disadvantages including concern among politicians about the dreaded word “tax,” and no certainty in achieving any specific level of emission reductions. In theory a tax may be viewed as distributing the burden of adapting to a low-carbon economy relatively impartially, unless specific measures are taken to redistribute the burden (see the case of British Columbia, below).

A cap-and-trade system allows for more flexibility in design and provides reasonable certainty that reductions will meet whatever mandated amount has been set: “While there is always a degree of dissension, many industry stakeholders favour the cap and trade system, as it leaves the carbon price-setting to the market but with some guidance provided by the system’s floor price,” said Robyn Gray from Sussex Strategy Group. “Leaving the price-setting to government, through a carbon tax, could create a level of uneasiness for some within industry.”

A key concern is that the cap-and-trade system may require extensive oversight if designed improperly, whether by governmental agencies or private verifiers, to ensure that reductions are real, additional and permanent – hence imposing potential transaction costs. One way to compare the two general options might be that a tax system makes for certainty on the price, but requires experimentation to arrive at a desired level of reduction, while C&T provides certainty on the amount of reductions, but not necessarily on the price. Although it’s designed to promote efficient solutions, it can’t predict the cost in advance and may incur higher system costs.

In fact, the choice between cap-and-trade and carbon tax as emission reduction mechanisms may be more theoretical than practical. They both lead to some form of carbon pricing and most real-world implementation systems contain measures that are hard to classify purely into one group or the other. Lisa DeMarco, of Zizzo Allan DeMarco, observes that the efficiency and effectiveness of any carbon pricing mechanism is highly dependent on the specific features of the instrument, and on how it interacts with neighbouring systems.

Alberta’s system, with credits for improving on an intensity baseline, was also listed as one of the possibilities. Observers have noted that such a system may induce businesses to spend extra on process efficiencies in a province or region with an expanding economy. That encouragement is absent where industry is stagnant or declining, and even routine maintenance of industrial capacity may be suffering. Baseline and credit appeared to be an unlikely choice for Ontario.

Finally, systems relying on regulations and performance standards have few fans among industry, as lacking the requisite flexibility and not allowing for capital stock turnover in the most efficient manner.

2. Take actions in key sectors

» transportation (public transit, low-emission vehicles, alternative fuels)

» buildings and communities (curbing urban sprawl, improving energy use in new and existing buildings)

» electricity

» more efficient industry

» agriculture and forestry

» waste.

3. Support science, research and technology

4. Promote resilience, manage risk

Several legal firms and policy experts, including Gowlings, Torys and Zizzo Allan DeMarco among them, have published summaries and commentaries on the discussion paper. Some noteworthy observations are excerpted below.

“This is Ontario’s third discussion paper on climate change in just over six years, following ones released in December 2008 and January 2013. Neither of those papers led to a carbon price or sector-specific emission limits. Some observers may ask whether this time is different. But anyone who has heard Minister Glen Murray speak on the topic … can tell he is fervently committed to fighting climate change, and eager to work with industry and other stakeholders.” (Gowlings).

“Much of the Paper is dedicated to making the case for quick and decisive action. It is wide in scope but thin on specific program or implementation details. Ontario’s role in the broader Canadian and international climate change context is also emphasized, noting that the globe is currently on track to see a four-degree increase in mean temperature this century. The Paper also notes that there is huge economic growth potential to be tapped as we move towards a low-carbon economy. The Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, Glen Murray, repeatedly references the six trillion dollars in new potential green industrial economic growth worldwide predicted to result from a transition to a low-carbon economy.”[1] (Zizzo Allan DeMarco)

Speaking at a conference on the province’s renewables procurement programs March 26, Minister Murray reiterated how seriously he views the issue – but also how he sees it as a force for improvement:

Speaking at a conference on the province’s renewables procurement programs March 26, Minister Murray reiterated how seriously he views the issue – but also how he sees it as a force for improvement:

“The science is pretty pervasive. In the last five years we have experienced the highest carbon emissions in human history. We are in the high-carbon scenario of the scientific projections. Even if we could shut down all carbon dioxide emissions, methane releases from the tundra would put climate change beyond our control. We have a few decades to make deep reductions.

“How prepared are we to seize the opportunities of a low-carbon economy? It’s not just about carbon pricing, it’s about carbon productivity. Productivity must be the mechanism for change. For years we hid behind a low dollar and cheap, bountiful natural resources, with the result that Canadian productivity is last or next to last in all measures of productivity, compared to the rest of the G8. Among our sixteen peer OECD countries, we rank sixteenth in almost every multifactorial category of productivity.

“So when you look at carbon pricing you’re looking at carbon productivity. How do you reduce GHG emissions in an economically positive way? The pricing system must be designed to drive higher levels of productivity. Our productivity gap with the United States is 25%. If we close that productivity gap, the average Ontario worker would have $7,000 more disposable income. [Carbon productivity measures are typically a measure of economic activity per unit of carbon emissions. – Ed.]

“If carbon pricing is a driver of productivity, the bottom line across the economy is positive. But that will not come as a result of a puff of smoke from Queen’s Park, or Ottawa. This is not a highly regulatory solution that wraps businesses and consumers in red tape. It has to be an aspirational partnership, that involves an unprecedented level of trust and collaboration between government and business leaders. This is not a competition between environment and the economy, it is the integration of those two things to a common purpose.”

APPrO recommended that the Government focus its immediate efforts on the key initiatives that are most likely to achieve the most GHG reductions, from the highest emitting sectors, at the lowest cost, in the short term. As part of its submissions in response to the province’s discussion paper, the organization proposed a three-pronged policy approach including a smart carbon pricing strategy “tailored to the very low emission realities of Ontario’s electricity sector,” addressing climate adaptation requirements,” and “leveraging Ontario’s clean electricity sector.”

The submission noted that “The proposed carbon pricing measures must be designed in a manner that does not result in perverse or unintended consequences in the northeastern North American electricity market. Leakage and cross border consequences must be considered as poor carbon pricing design parameters may result in increased GHG emissions across borders and hurt the competitiveness of Ontario’s low emitting electricity sector. ... All proposed carbon pricing design parameters should be modeled thoroughly by the IESO/Ministry of Energy and discussed with electricity stakeholders before implementation.”

APPrO said the mechanisms should “Expressly address the critical role of the existing natural gas fleet in reliability and the transition to a lower carbon economy. Any carbon pricing measure must reflect the reliability of Ontario’s system supply mix and unique grid flexibility and reliability considerations. The natural gas fleet is also integral for ongoing and enhanced renewables integration in the Province and therefore the transition to a lower carbon economy. … New measures should be targeted at achieving GHG reductions from the highest emitting transportation, industry and buildings sectors that constitute 81% of current provincial emissions.”

APPrO stressed that gas-fired generation technology and related emissions are set at the time of construction of a generation facility, and facility-specific emission reductions are essentially only achieved through decreasing power production or asset retirement and argued that “renegotiating all CES and NUG contracts for no appreciable emissions benefit is a significant and unwarranted cost and administrative burden to government, generators, customers and the electricity sector.”

The organization recommended that the province cap electricity sector emissions at the current absolute and emission performance levels: “Existing gas-fired generation facilities should effectively be grandfathered at existing emission performance standards until the end of their useful life. This may be done without re-opening existing CES and NUG contracts by not requiring an emissions allocation for such facilities unless the facility exceeds its current emission intensity level or reaches the end of its useful life. … New emitting facilities would be required to purchase emission allowances to cover GHG emissions in excess of the rolling Province-wide electricity sector emissions intensity level. Electricity importers would also be required to purchase emission allowances to cover deemed emissions associated with the imported electricity in accordance with the ‘first jurisdictional deliverer’ requirements of the WCI as implemented by Quebec and California.”

IPPSO FACTO invited commentary from informed observers on three questions:

• What degree of emissions reductions would be reasonably attainable in the short term, technically and economically, and then again in the long term given feasible technological improvements and suitable policies/regulations?

• What kind of system is likely to work best for Ontario: a carbon tax, cap and trade, baseline plus credits, or some kind of hybrid?

• How to find an appropriate balance of effort between mitigation and adaptation?

Calling for change in the systems of power generation

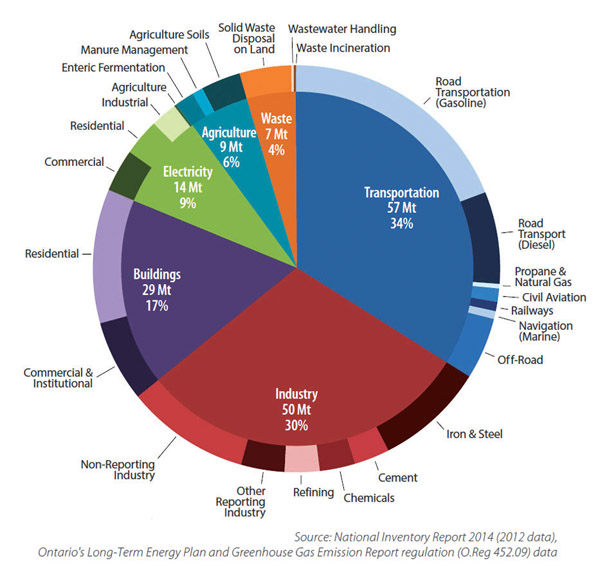

Energy system analysis begins with production. Overall, GHG emissions from electricity generation in Canada as a whole are already very low compared with other parts of the world, with only 23% of Canada-wide and approximately 3% of Ontario emissions coming from generation using fossil fuels[2]. In Ontario, electricity generation after the coal phase-out accounts for just 5% of GHG emissions[3] compared to 34% for transportation, 30% for industry and 17% for buildings. How much further GHG reduction can reasonably be expected from Ontario electricity generation, which has already accomplished the largest sectoral reduction in North America if not the world, by the closing of the coal-fired plants?

Energy system analysis begins with production. Overall, GHG emissions from electricity generation in Canada as a whole are already very low compared with other parts of the world, with only 23% of Canada-wide and approximately 3% of Ontario emissions coming from generation using fossil fuels[2]. In Ontario, electricity generation after the coal phase-out accounts for just 5% of GHG emissions[3] compared to 34% for transportation, 30% for industry and 17% for buildings. How much further GHG reduction can reasonably be expected from Ontario electricity generation, which has already accomplished the largest sectoral reduction in North America if not the world, by the closing of the coal-fired plants?

Bruce Power, operator of the Bruce nuclear generating stations, issued a statement in 2014 highlighting the role that nuclear energy has played in reducing GHG emissions in Ontario. “The return of 3,000 megawatts of Bruce Power nuclear over the past decade has generated 70 per cent of the energy needed to shut down all of Ontario’s coal plants. ... More electricity from Bruce Power nuclear means cleaner air for families across Ontario,” said James Scongack, Vice President of Corporate Affairs at Bruce Power. “We recognize the future refurbishment of the rest of our nuclear units is a key pillar in the province’s plan to keep the air clean.” In 2013, production from Bruce Power nuclear helped Ontario avoid 31 million tonnes of CO2, which is the equivalent of taking six million cars off the road, he noted.

In mid-March a group of over sixty academics from a range of areas of study, under the heading Sustainable Canada Dialogues, presented a set of recommendations at a conference in Montreal. The group is part of an international Sustainable Dialogues program by UNESCO and McGill University. It called for a complete, or near-complete, replacement of electricity from fossil fuels with renewables – “Canada could reach 100% reliance on low carbon electricity by 2035,” says the Sustainable Dialogues group. It sees an 80% reduction in emissions from the entire economy by the middle of the century – which also happens to be a key reference point of the provincial discussion paper. Nonetheless, without major technological change, there is little doubt amongst power sector experts that natural gas fired generation will be key to maintaining grid reliability in the transition to a lower carbon economy.

Jose Etcheverry, Associate Professor in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University, points to northern Europe, particularly Germany and the Scandinavian countries, as an example of doing it right. For one thing, their commitment to renewables is working, he says. Denmark now has so much wind that the proportion of electricity generated annually – energy, not capacity – has reached 40%, and is heading for 50% by 2020. There are now many hours out of the year when the country’s entire electricity supply comes from wind. The country, long a showcase for how to do cogeneration and district energy right, now has so much capacity in wind that CHP plants are closing, and district energy systems are relying on the offshore windfarms to drive the district energy systems, with surplus electricity stored as hot water. They’re providing locally grown food from greenhouses heated with electricity from wind. Norway is in the process of connecting, via undersea cables, to the rest of Europe and also to Scotland, and using the country’s hydro power to balance wind and solar from the grid.

Far weightier according to the way GHG emissions are accounted for are the other sectors in which energy is both produced and consumed, chief among them transportation, industry and housing. This article cannot do justice within the available space to the level of detail any level of analysis of reductions in those sectors would merit. A few high-level observations will have to suffice.

On that subject, however, AMPCO President Adam White observed, “Some of AMPCO’s members have processes such that emissions are linear with production, because the carbon is in the feedstock, or is intrinsic to the chemistry of the process. If they were to reduce emissions, it could only be by curtailing production, and then they have an underutilized asset with deteriorating economics. There are no efficiency gains to be made from the chemistry. You can’t crack ethylene or manufacture fertilizer without natural gas. There is a lot of carbon intrinsic to our way of life. But over time there are a lot of sectors amenable to dematerialization, changing modes, fuel switching, greater efficiencies. Carbon policy should incentivize the most promising of those opportunities first.”

It may not be coincidence that the Ontario discussion paper listed transportation first, and energy for buildings second, among the sectors to be addressed for conservation efforts. On the way energy is used in transport, Minister Murray himself commented on the value of a transport system that relies more on electricity for its energy, and on rail transport. If Ontario’s auto fleet relied on electricity to a significant degree, he said, we wouldn’t have to worry about surplus nighttime generation from the nuclear units – automobile batteries could soak up the surplus during the night and use it to commute during the day. There’s a gigafactory set up in Nevada making car batteries that will allow 200 miles worth of travel, he pointed out, and it’s powered entirely by solar and geothermal-sourced electricity. By implication he suggested we need to be doing comparable things here.

Both Prof. Etcheverry and Prof. Danny Harvey at the University of Toronto appear to second that emphasis. Both call for greater integration of the electricity grids across the provinces, using surplus generation from Quebec’s and Manitoba’s hydro generation, with energy storage, as by pumped water, to maximize the use of low-carbon electricity production. However, observers have noted that the current configuration of federal-provincial responsibilities and the very different approaches to technology, ownership and capital investment between the different provinces make this a very doubtful solution in the near term.

For the built environment, the 80% reduction by 2050 that the province is suggesting is probably feasible, said Prof. Harvey in an interview, if the province were to go “all out” starting now to achieve it. He believes Ontario would have to rapidly upgrade the energy standards for new buildings, implement a plan for deep retrofits of the existing building stock between now and then – a 35-year period, meaning retrofitting about 3% of the building stock per year. “We have incremental change now in the building code, but it needs to go a lot faster,” he observes. “We need factor-of-two improvements in building energy efficiency, not 10 – 15% every five years. We need to improve space heating and hot water, emphasize passive heating designs, and get out of fossil fuels for space heat,” he believes. Harvey contends that Ontario will need to reduce the energy demands of older buildings from the ‘60s and ‘70s by a factor of ten – redo the exterior, make them airtight and put in heat exchangers and ground source heat pumps. Once the heat loss is low enough they can store surplus heat and run heat pumps just at need, leaving space heat as a dispatchable load.

What carbon pricing approach is best?

In the immediate term, this may prove to be the subject that prompts the most intense discussion in the media and amongst market participants. No doubt preferences already exist within various sectors. Lisa DeMarco reiterates that the distinction may be somewhat artificial: “The key consideration is how the system is designed, and how it interacts with neighboring systems to avoid GHG leakage.”

In the immediate term, this may prove to be the subject that prompts the most intense discussion in the media and amongst market participants. No doubt preferences already exist within various sectors. Lisa DeMarco reiterates that the distinction may be somewhat artificial: “The key consideration is how the system is designed, and how it interacts with neighboring systems to avoid GHG leakage.”

Adam White offered the following:

“Carbon taxes are more efficient in theory. But we need to consider the complexity of the status quo. In the electricity sector ratepayers are going to be paying for 20 years to finance the phase-out of coal, and the displacement of natural gas and nuclear power, with renewable energy. We’ve signed a 20-year deal on that. So you can imagine our concern, having just built, and not even finished building, 11,000 MW of gas-fired generation, that we would then be subject to a further tax on emissions from those facilities. However, if the tax were revenue-neutral, and the revenues were used to create market-based incentives to reward truly efficient behaviour, we could maybe support that.

“But the complexity of the situation includes what’s happening federally, in Quebec, BC, and what’s going to be happening state by state in the US. There are already cap and trade systems, as in Quebec, pursuant to the WCI, on the process emissions from large emitters. To the extent that we trade with Quebec and more to the point, have to compete with them, it might be practical in Ontario to apply C&T to certain sectors, to deliver certainty on the amount of emissions, both from the government’s perspective on capping emissions, and from the industry’s perspective on understanding the parameters within which they operate. Tell us what the conditions are on the license to operate, and we’ll make a business decision about whether we’ll continue operating. Adding on layers of tax creates an uncertain environment.

“If you have a tax on carbon that is uniform across the economy, there should be some form of rebate that makes it revenue-neutral, so that ratepayers are rewarded for the investments they’ve made. Frankly it’s better for Ontario and for ratepayers if we displace gas and nuclear at the margin. Renewables and conservation, demand response, should be incentivized with great prices and market-based incentives. A carbon tax is a way of doing that. But if you want to cap carbon emissions in certain sectors of the economy in a way that doesn’t disadvantage them in trade with other jurisdictions, then C&T might be the way to go. This is Ontario, we have to think in hybrid terms.”

QUEST (Quality Urban Energy Systems of Tomorrow) in Ottawa, which is active in promoting cogeneration and district energy systems in particular, suggests that the Ontario government echo the practice in Quebec: “If the government does want to introduce a carbon price, it should do so on all fuels at their source, so that no one facility will be penalized for their choice of having combined heat and power. We have gone further and made a recommendation that if the government does proceed with a cap-and-trade system, that they effectively back out the GHG emissions associated with heat production from CHP facilities.” Director of Research and Strategic Initiatives Richard Laszlo explains that about 2/3 of the carbon emissions are associated with the useful heat output of a combined heat and power system, so that under a cap-and-trade system, generators selling power from CHP should only pay the levy on the fraction of the source energy used to generate electricity.

Etcheverry allows for a hybrid system, which would allow Ontario to become a full participant in the Western Climate Initiative. But setting up a trading system is a lengthy process, he adds. It’s complicated and subject to gaming. In Europe, it’s taken several iterations, and is still not working very well, he says. The Waxman-Markey bill introduced, but not passed in the United States Congress, has been praised by some as at least trying to get something done, but also criticized as weak and riddled with concessions to special interests. So let’s copy what works right away, Etcheverry says, and then have a conversation down the road as to whether we want to link with Quebec and California.

However, he goes on to say, “None of these are silver bullets. You need to look where it’s successful in both reducing emissions and maintaining a robust economy – Germany, the powerhouse of Europe. They have a number of policies for sustainability, not just carbon taxation and emissions trading – renewable energy laws, very ambitious programs toward 100% renewables, strong RD&D incentives. Close to 400,000 are now employed there in the renewables sector.” Of course there are other views on such propositions, some widely-held, and many contend that that this type of approach is economically dangerous and unsustainable.

It’s worth noting that the governments of Ontario and Quebec have a memorandum of understanding, signed in November 2014, agreeing to collaborate on concerted climate change actions, including harmonizing GHG reporting requirements and exploring the use of common market-based mechanisms.

International trading

Quebec, of course, is a long-standing member of the cap-and-trade system with California, under the Western Climate Initiative, initiated in 2007. Ontario contributed to the Initiative, as did British Columbia, though currently only California and Quebec have a fully operational cap-and-trade arrangement, with two joint auctions having taken place as of the date of this writing. The February 2015 joint auction saw 73.6 million allowances offered and sold.

Under the arrangement, California has committed to reducing its emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, while Québec plans to reduce emissions 20% below 1990 levels by the same date.

A 2014 study[4] of the arrangement between Quebec and California implies that the system already seems to be having an effect, with emissions in both California and Québec having grown more slowly than their respective national averages relative to 1990 baseline levels.

Quebec and California are credited with going about the job in a serious way. In the study’s words, “The WCI framework is more comprehensive and stringent than other subnational efforts to reduce emissions in North America. For instance, the WCI framework will extend an emissions cap over a number of economic sectors instead of only power generation (c.f. RGGI), will not exempt industrial emissions (c.f. BC carbon tax) and will require absolute reductions as opposed to per-capita emissions performance improvements (c.f. Alberta’s Specified Gas Emitters Regulation).”

The study summarizes the WCI’s targets: “During the first commitment period, from 2013-2014, the emissions cap will address only emissions in the energy and industrial sectors – accounting for approximately 36% and 29% of total emissions in California and Québec, respectively. From 2013 through 2014, the cap decreases by about 2% annually in both jurisdictions. At the beginning of the second compliance period, coverage expands to include the transport sector in 2015, at which point approximately 87% and 77% of emissions will be covered in each respective jurisdiction. Between 2015 and 2020, the cap reduces at a rate of approximately 3% and 4% per year in California and Québec, respectively.”

PhD candidate David Houle, analyzing GHG reduction policies at the University of Toronto, explains that in Quebec, beginning in 2007 the transportation sector was initially covered by a fuel tax, revenues from which were directed to a Green Fund, but beginning in 2014 the cap was phased out and the sector is now part of the overall cap. The cap is applied to fuels at the point of import to the province, with importers with over 25,000 tonnes of emissions a year buying allowances at auction, and able to buy and sell credits. In the first year 90% of allowances were free, but granted on the basis of historical performance. The effect of the inclusion of transportation is to bring the sector within the terms of the WCI and enlarge the market for credits.

It’s also notable that in either jurisdiction companies can only buy credits worth up to 8% of the GHG emissions to be covered during the associated compliance period. (Quebec regulation s.20.)

Mr. Houle observes that for a while there was some concern over a possible flight of investment from Quebec because the reductions that California has targeted in its electricity sector will be cheaper, and the price of allowances lower, than those in Quebec, where emissions in the sector are already quite low thanks to its reliance on hydro power. Encouragingly, in recent auctions conducted jointly they have been about equal.

Interestingly, he adds that the industrial dynamic in Quebec is changing as a result, with some sectors able to generate credits getting an advantage while oil and gas see themselves as disadvantaged. A group of businesses, including agricultural producers, has formed an association, Coop Carbone, to assist members with emissions reductions, generation of offset credits and carbon risk management. The December 2014 – January 2015 issue of IPPSO FACTO carried a story on a project in the town of Ste. Hyacinth that will be generating biogas from agricultural waste and injecting it into the system of Gaz Métro.

A hybrid system may in the end be a practical solution. To quote the University of Ottawa study again, “In both California and Québec, cap-and-trade is but one piece of a much more comprehensive package of policies designed to address climate change. The striking feature of California’s strategy is that the state expects to attain 85% of its 2020 emission reduction through complementary policies, with the cap-and-trade system serving as a backstop measure to make the system more robust and link its different components. If a complementary policy does not deliver its intended results, the cap ensures that incentives to reduce emissions remain. Though similar estimates about the role of Québec’s complementary policies are not known, it is safe to assume they will also play an important role. In other words, the cap-and-trade systems in both jurisdictions serve as a support measure to enhance the effectiveness of other programs by putting a price on carbon. In turn, complementary policies allow government to retain an important degree of control over climate policy while also targeting emission sources that are generally unresponsive to prices.”

In fact, Ontario has suggested in its discussion paper that certain “sector specific actions” yet to be defined will be part of its approach to emission reduction.

The politics

It’s probably inevitable that a proposal with goals as ambitious as laid out in the Ontario government’s discussion paper, with the deep structural changes it will necessarily imply, will have to be sold to the provincial electorate. However, there are still voices on the political right that can be expected to rise in opposition to any substantial plan, says political analyst Rob Silver. The NDP itself can be expected to have at least an ambiguous reaction, he says: “They fluctuate between their downtown Toronto green constituency and some of their more populist industrial constituencies, so I don’t think it’s a given at all that the NDP will be in favour of whatever action should emerge. We’ve seen at the federal level that the NDP have opposed all efforts at a carbon tax, and in BC as well.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Silver thinks that with their majority in the legislature the Wynne government will be able to push a serious climate plan through.

“Premier Wynne feels she was elected on a progressive mandate, and in 2015 that includes having a serious plan around climate change. There will obviously be components, both of the opposition parties as well as industry, who oppose it. I think there are many parts of industry who will embrace it, who have been suffering because of uncertainty at the federal level and will welcome certainty at some form of carbon pricing, whether it comes in the form of a tax or cap and trade.

“Like any plan, the devil will be in the details, since we all know it’s extremely complicated – which is why I think they’re doing the right thing in taking their time to get those details right. It will be interesting after the federal election, how the Ontario, Quebec, Alberta and potential federal plans interact. That’s where, to some extent, the rubber will hit the road.

“They’ll sell it by showing that they’re working with the other provinces, by talking about why this is part of a modern forward-looking economy. I don’t think they’ll have much trouble selling this.”

As to whether this is best left to the provinces or to Ottawa, Mr. Silver observes, “Both. We live in a federation, and the way powers are divided, lots of components – resources, regulation of industry, are at the provincial level. That said, having ten completely uncoordinated climate change policies is not the best way to run a country. We need the federal government working on climate change and some kind of pricing coordination function if nothing else, but in a vacuum the provinces have taken it up.”

Might a substantial provincial plan push the federal government to take action where it’s been slow to do so?

“It could. We’ll have to see who’s Prime Minister in six months.”

Of the unresolved political questions remaining, one of the largest relates to the superstructure required for managing a long term cap and trade regime: How will it allocate the caps among the different sectors? How will adjustments be made over time? What will be the political implications of those allocations and adjustments? Is it not likely that there will have to be careful political calculation involved, and some degree of transparency to minimize political interference? How will the inevitable pushback from some quarters be managed? Is there in fact potential here for a political quicksand with serious consequences for the governing party?

“With carbon pricing, the devil is truly in the details,” Ms DeMarco emphasizes. “Smart policy requires smart system design that reflects the entire Ontario energy and economic context.”

The Wynne government has been careful to emphasize collaboration and stakeholdering as the primary way forward on this, and it will certainly receive no small amount of input. The next few months are likely to reveal which parts of the puzzle will be addressed first, and the pace the government intends to set, at least for those upcoming issues. The longer term is an open question.

With files from Stephen Kishewitsch

Ten guiding principles toward a low-carbon economy

From the Environment Ministry’s climate change discussion paper:

1. Act now. The larger the delay, the larger the problem will grow

2. Leadership with innovative practices on the international stage

3. Learn from best practices

4. Support new technologies

5. Integrate economy and environment in policy making

6. Market-based instruments

7. New and existing infrastructure will be connected in “climate smart” ways

8. Ongoing flexibility in adapting to changes

9. Collaboration with all levels of government and private sector

10. Track progress, assess risks.

Related events and sources

• The government's "Ontario's Climate Change 2015" discussion paper was placed on the Environmental Registry, with a period for public discussion open until the end of March. The government is to release a strategy later this year.

• The 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Framework Convention in Climate Change (COP21 and the UNFCC) is scheduled for November 30 to December 11 in Paris and that this discussion paper is to help inform the government's overall Strategy, which will be released later this year.

• An invitation-only Pan-American Summit on climate action is scheduled for July 7 – 9 in Toronto.

• Memorandum Of Understanding Between The Government Of Ontario And Le Gouvernement Du Québec Concerning Concerted Climate Change Actions 2014, at news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2014/11/memorandum-of-understanding-between-the-government-of-ontario-and-le-gouvernement-du-quebec-concerni.html

• Energy [R]evolution: A sustainable energy outlook for Canada, 3rd edition, 2010, by Greenpeace, 120 pages. Greenpeace has also produced a 2014 equivalent for the United States, and another dated 2012. At www.greenpeace.org/Canada > Our Campaigns > Energy > Energy [R]evolution

• "Acting on Climate Change, solutions from Canadian Scholars, March 2015, at http://biology.mcgill.ca/unesco/EN_Fullreport.pdf

• Ontario’s Climate Challenge: Getting back on track, by Environmental Defence, February 2015, at http://environmentaldefence.ca/reports/ontarios-climate-challenge-getting-back-track.

[1] “The New Climate Economy Report 2014,” by The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, estimates that US$6 trillion will be spent annually to meet global infrastructure needs over the next 15 years. Chaired by former President of Mexico Felipe Calderón, the Commission comprises former heads of government and finance ministers and leaders in the fields of economics and business. http://newclimateeconomy.net/

[2] Sustainable Canada Dialogues, “Acting on Climate Change,” p 22

[3] Environmental Defence, “Ontario’s Climate Challenge: Getting back on track” page 4, reflects 9% of emissions in 2012 and following the coal phase out in 2014 they are anticipated to be 5 MT or approximately 3% of Ontario’s emissions in 2014.

[4] Mark Purdon, David Houle and Erick Lachapelle, “The Political Economy of California and Québec’s Cap-and-Trade Systems”, University of Ottawa