Ontario’s system for procurement of long term power supply, which many believe underpins the sector’s stability, is facing strong pressures for change from several directions. What kinds of change are anticipated?

Based on current supply and demand projections, Ontario will not need major new power supply until approximately 2020 when the refurbishment of a series of nuclear generating units is scheduled to begin, along with the retirement of the Pickering station. Although it can take longer than 3 years to bring most conventional forms of new generation into service, many observers believe the current supply situation creates a natural opportunity for a slowdown in the pace of procurement during which stakeholders and officials will likely consider options for substantive changes to the procurement system. This does not mean of course that procurement programs will stop during the review period, but they are unlikely to ramp upwards across the board.

Based on current supply and demand projections, Ontario will not need major new power supply until approximately 2020 when the refurbishment of a series of nuclear generating units is scheduled to begin, along with the retirement of the Pickering station. Although it can take longer than 3 years to bring most conventional forms of new generation into service, many observers believe the current supply situation creates a natural opportunity for a slowdown in the pace of procurement during which stakeholders and officials will likely consider options for substantive changes to the procurement system. This does not mean of course that procurement programs will stop during the review period, but they are unlikely to ramp upwards across the board.

The pressures for change in the province’s procurement systems come from three primary sources:

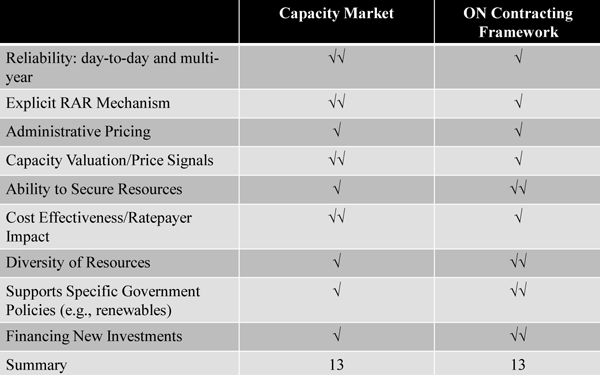

1. As a matter of public policy, agencies of the provincial government, in concurrence with the province’s Long Term Energy Plan, are pursuing development of capacity auctions as an alternative form of procurement. Some believe that such auctions will be more market-based and cost efficient than other forms of procurement.

2. There has been rapid development of green energy capacity over the last five years, largely built on contract-based mechanisms with fixed prices, which has caused political reaction and created conditions for a slow-down in conventional green energy procurement and related interest in moving towards other forms of procurement.

3. The procurement system will likely adapt to reflect increasing disparity amongst customers in terms of their appetites for centrally provided reliability services – functions that have conventionally been inseparable from bulk power supply. Changes in technology are increasingly enabling customers to separate investments in reliability from investments in supply, and to meet their own needs for specific levels of reliability, whether they are higher or lower than the standard levels of reliability that are procured centrally. Even if customers do not self-provide, economic pressures will likely force change in the assumptions used by central agencies in their procurements, leading to systems that will allow customers with different reliability preferences to have their needs met more precisely, and to enjoy the related cost savings.

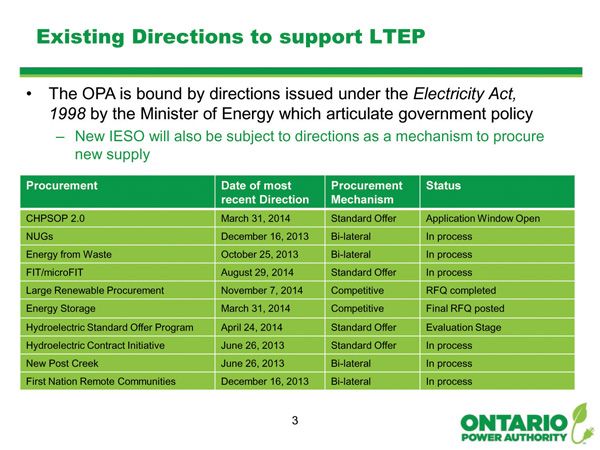

Speaking on behalf of the OPA at the APPrO 2014 conference on November 18, Barbara Ellard outlined the three major types of procurement tools the OPA has at its disposal: Competitive processes, standard offer procurements, and bilateral negotiations. She described a number of active processes underway as a result of ministerial directives. (See chart above.) “You have to have multiple tools in the toolbox so you can deal with the various different situations,” she said.

Speaking on behalf of the OPA at the APPrO 2014 conference on November 18, Barbara Ellard outlined the three major types of procurement tools the OPA has at its disposal: Competitive processes, standard offer procurements, and bilateral negotiations. She described a number of active processes underway as a result of ministerial directives. (See chart above.) “You have to have multiple tools in the toolbox so you can deal with the various different situations,” she said.

Jason Chee-Aloy of Power Advisory LLC has examined capacity auctions and long term supply contracting as alternative tools for meeting resource adequacy requirements. He expects to see refinements developed for most if not all of the options. Focusing on contracting, he argues that, “There are smarter ways to contract. You can design the rules to get a lot more competition. For example, you could have things like Swiss challenges where applicants are given a specific period of time to try to out-do the best proposal received to date. Another option that would make a lot of sense would be to use a “descending clock.” Under a descending clock system the buyer announces a maximum price and sees how many people bid and for how much capacity. Then it tries another round at a lower price, and so on until it reaches appropriate levels of supply and price. Ontario could make some headway during the upcoming reviews, Chee-Aloy suggests, by examining alternative ways to improve the system of contracting.

Chee-Aloy also observes that more effective system integration and cost reductions could be achieved if the buyer is able to use greater flexibility in the interpretation of standard rules and application of contract terms. In his previous role as head of generation procurement at the former OPA he encountered numerous situations where rigid contract terms “clashed” with market rules and produced sub-optimal outcomes. Problems of this nature can be addressed with prudent adjustments to the system by which standard contract terms are applied, he suggests.

With respect to relying on a yet-to-be-developed capacity auction, he notes that, “If you are looking at incentivizing new entry, ensuring longer term developments, and achieving more certainty for financing and everything that goes with new infrastructure, contracts typically are better.” However, he believes that capacity auctions can be helpful for lining up short term arrangements, particularly those focused on securing underutilized residual capacity. For the time being however, experience is demonstrating that capacity markets are subject to continual change, which makes them relatively uncomfortable for long-term investors.

At the same time, new procurement of any type is facing added risk and complications from the potential encroachment of small scale distributed generation (DG). In some cases, customer-owned generation will be able to undercut the cost of centrally-generated supply, creating economic challenges in the longer term for any major new supplies that are centrally procured today. Both photovoltaic and gas-fired power generation technology options are experiencing cost reductions that are bringing them closer to the all-in cost of grid power, and which are in fact already attractive in certain niche situations. While examples of DG actually undercutting the cost of grid power in Canada are rare at the moment, the risk that the new distributed technologies could become more widespread weighs on the designers of any form of procurement and likely dampens any procurement proposals that could have hefty price tags.

Ontario’s procurement system is remarkably complex. Although rarely acknowledged in its entirety, because of the “hybrid system” and the numerous initiatives that have been added over the last decade, there are at least eight parallel forms of procurement or adding capacity to the system:

1. Central contracting as practiced through the Clean Energy Supply program, RES and the soon-to-be-finalized LRP program, using competitive RFPs

2. Central contracting through standard offer programs and Feed-in-Tariff programs

3. Micro-FIT and Capacity Allocation Exempt projects, essentially a subset of the above, but with a different set of program rules, limits, and connection procedures, for renewable projects under 50 KW

4. Bilateral negotiations, also resulting in centrally-procured contracts (This approach has been used to date in Ontario primarily for nuclear and large CHP)

5. Regional planning, leading to another form of contracting, yet to be determined, for local reliability

6. IESO procurement of services, usually through RFPs, such as the recent storage RFP, but also including a bevy of other legacy programs such as hydroelectric-specific procurement, RMR contracts, etc.

7. Capacity auctions, in a format that is currently the subject of extensive stakeholdering by the IESO

8. Development without centrally-administered contracts, usually for load displacement, but not necessarily limited to load displacement. (This is not actually a form of procurement, but operates in the same realm, and acts an alternative to the various forms of procurement.)

Analysts like Chee-Aloy are concluding that as the overall supply situation remains in surplus, participants are likely to see procurement systems redesigned in an effort to shift risk from the rate base to developers. In contrast, during periods when there is a perceived risk of future shortages, it is often considered acceptable for the rate base to bear increased amounts of development risk, in order to ensure adequate capacity. The coming business cycle appears to be one in which there will be pressure to move risk back to the development industry, as Ontario’s market is projected to be in surplus until around 2020. In some situations the industry is able to manage certain types of development risk, and can offer cost savings to the ratepayer, given the right opportunities. Only time will tell if such savings are going to be available in Ontario.

The new IESO has announced a series of consultations titled “Industry Dialogue on Renewable Procurement.” These meetings are to discuss the “proposed enhancements to the 2015 Feed-In Tariff (FIT) and microFIT programs and to review the stakeholder feedback received on the Large Renewable Procurement (LRP) draft Request for Proposal (RFP).” They are the first consultations of this type led by the generation procurement group under the auspices of the newly-amalgamated IESO. In combination with the parallel consultations on the development of a capacity auctions, and related efforts on other procurement issues, it is clear there will be a lot of discussion and stakeholdering on procurement in the months ahead. (See related article titled “LRP process transferred to IESO”.)

It will be a key test of the generation industry’s mettle as to whether it is able to respond to these pressures for change, and develop reforms that will preserve the existing strengths of the current procurement system while adapting to changing circumstances.