A number of Aboriginal communities in Canada have faced major decisions on how to deal with power project proposals in recent years. Chris Henderson of Lumos Energy, an advisor and financing specialist who has worked with several such communities, believes the experience has allowed stakeholders to gain new insight and capabilities that will prove to be of great value for them in the long term. In fact, some of the lessons learned may well have value for communities well beyond Canadian Aboriginal groups.

Speaking at the APPrO 2013 conference on November 20, Henderson noted that any proposition for a power project on traditional Aboriginal territory is likely to be judged largely by the kind of long term value the community can realistically expect to see from the project. The overall economic potential is significant, he said: “We are well on our way to Aboriginal communities benefitting from clean energy projects more economically than any other single source of economic activity, whether transport or mining or fossil.”

Citing several Aboriginal power projects in or near commercial operation (Lower Mattagami, Okikendawt, Kitchi-Nodin Wind, Big Beaver Falls, Dokie Wind, Pehonan Hydro, Wuskwatim, Freda Creek, and Ojibway Biomass) Mr. Henderson explained how, as an advisor to and for First Nations, he considers one of his main objectives to be “making the pie bigger” so proposals move faster, and the projects become more economic and able to deliver more results, so that everyone can derive more benefits.

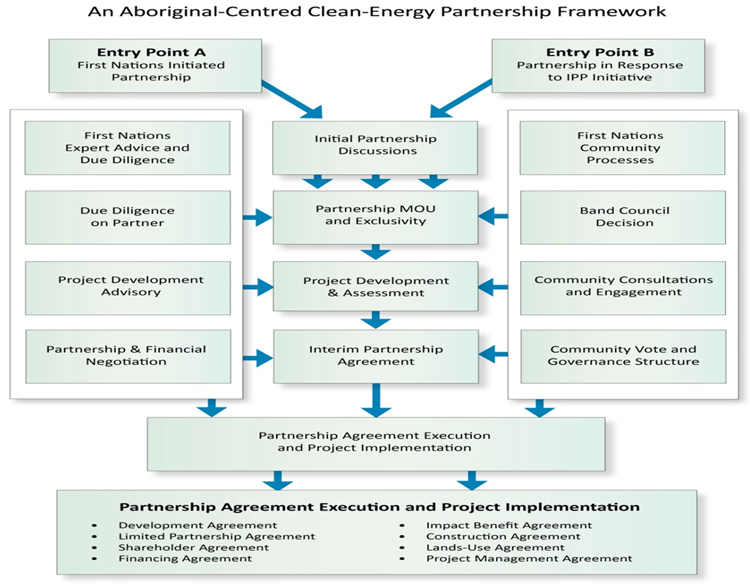

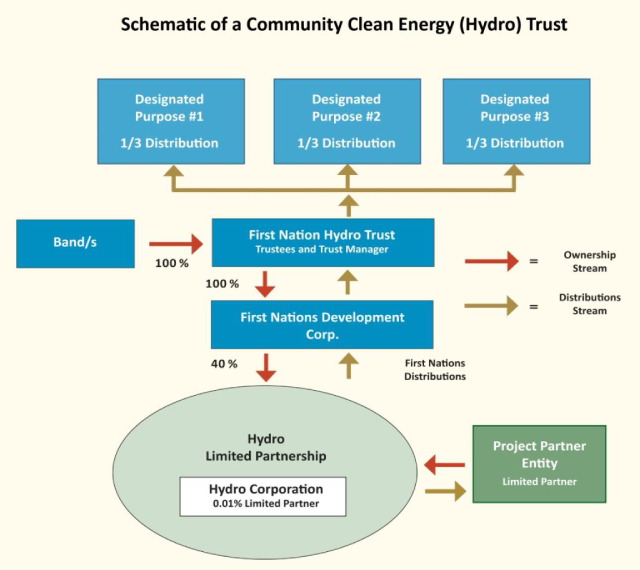

Based on Henderson’s experience, in most cases a community-based development process results in a project designed for future generations, where the community would own from 25% to 40% of the initial investment, with something like 5% interest on long term debt, with the remainder being financed by the community for their share of the leveraged equity, along with private partnerships. Those could be utility or development companies, engineering or financial firms, or a combination thereof.

“We know we need more clean energy sources, and that Aboriginal peoples will be part of it,” Henderson said. “Whether that goes ahead or not, however, is a matter of how – how to strike partnerships, how the community makes decisions to proceed or not, how the dividends are shared within the community and with private partners, how the environmental assessment is structured, how the partnership agreements are formalized, how the benefits are shared and generated, how finances are generated.” Mr. Henderson returned several times in his talk to this theme of “How.”

Henderson is the author of a recently published book titled “Aboriginal Power – Clean Energy & the Future of Canada’s First Peoples.” In the book, he identifies three tests to help meet environmental and Aboriginal community requirements. The Clean Test (are we replacing gas or coal with renewable energy source), the Green Test (are you affecting habitat, fisheries, traditional livelihood or impacting on ecosystems) and the Sustainable Test (primarily related to the partnership with Aboriginal communities). Even when a power project passes these tests the entirety of the project must still be considered – how it is designed, how it’s constituted and the impacts related to the project. Everything is determined by the nature of the project, the community, and the partnership, he says.

Most often a developer has to deal with several communities, with several territories and claims, and this can be a challenge. Mr. Henderson related an experience dealing with three different tribes in the Saskatchewan region who have been closely joined socially, yet have never done anything economically together or with anyone else. Even under these favorable conditions it took three to four years to work with the elders and the communities to decide how they could share in all aspects of the project – the governance, the dividends, etc. The degree of claim needs to be studied, the history and archaeology, the relative contributions from the communities, and then an agreement needs to be developed, sometimes with the assistance of a formal arbitration process.

First Nations are not stakeholders, they are rights and territory holders, he stressed. The current consultation process is necessary but insufficient in recognizing the importance of traditional territory. What is needed is a process and relationship-building that is proactive, sustainable and substantive. Unfortunately this is currently not happening – a core reason for many projects not working. Early stage engagement and collaboration in order to forge relationships requires spending time with the communities, as Mr. Henderson has done with the seven or eight First Nation communities that have accepted him as an honorary member. The traditional style of project development is one of the major reasons projects are failed or stalled.

He summarized key recommendations as follows:

1) Look at the traditional territory

2) Be more substantive on the upfront process and the nature of the relationships and

3) Arbitrate where there are multiple territory claims.

Mr. Henderson drew a parallel between the two-row wampum (figure {slide 23}), a traditional treaty document that conveys the idea of independent communities sharing a river – and a style of development process that has parallel consultations within the community and between community and developer (fig. {slide 24}). In the case of the Inukjuak River the internal process took two years, with high participation levels. In the case of the Dokis River, a similarly thorough consultation, including environmental NGOs, the project proceeded six months faster than it would have otherwise. Do the comprehensive, holistic thing, he advised, not the expedient thing. Without full community participation, a Band Council resolution isn't worth the paper it's written on. With it, implementation is likely to be enhanced and more successful. As a result of such a process, the Sooke First Nation went far beyond an initial solar project to put solar panels on thirty buildings, not just the original one.

Mr. Henderson identified some lessons:

• Make sure the project is a good fit for the provincial power system

• Establish early, up-front and substantive partnerships

• Hard-nosed feasibility assessment

• Make ‘the pie bigger’

• Focus on speed

• Build holistic projects

• Hardwire multiple benefits

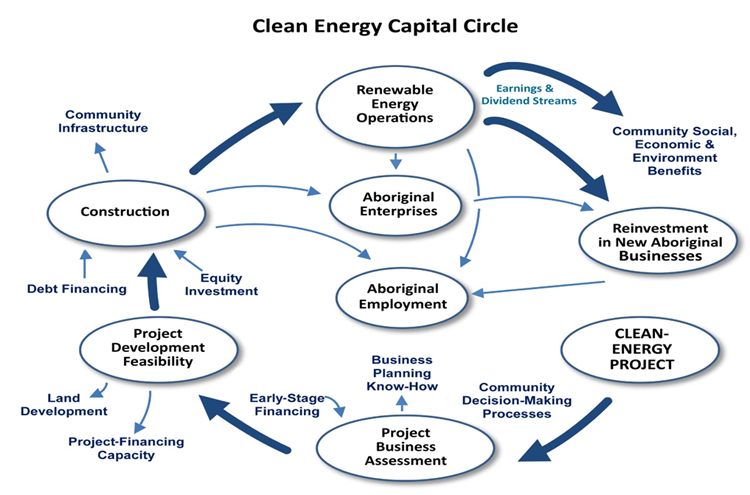

• Create a Clean Energy Capital Circle by engaging women and children

• Bring in the whole community, paying particular attention to women and youth, making sure they see the project as part of their future

• The Details of Democracy

• Structuring Success

• Transparent Reporting

• Deliver, Deliver, Deliver…

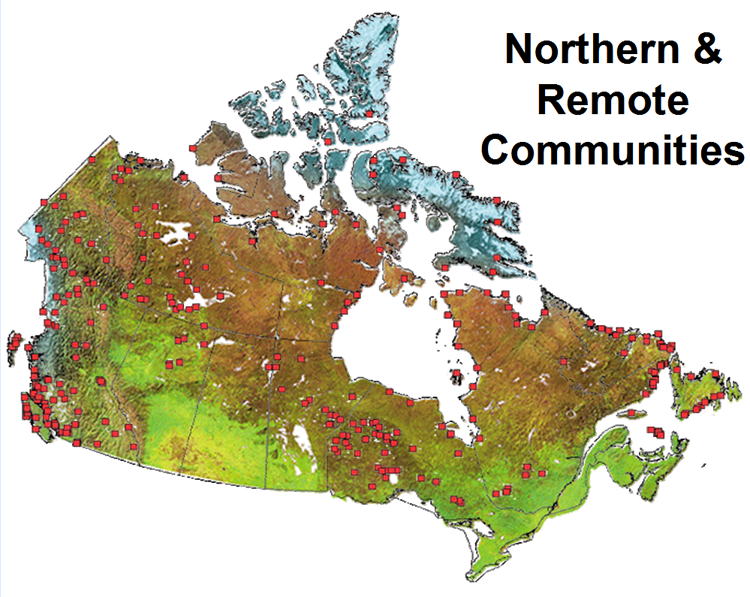

Mr. Henderson is working to establish a learning circle for the purpose of creating a Northern Power Purchasers Agreement that will assist project development in remote communities where project financial viability cannot rely on a grid-connected power purchase agreement.

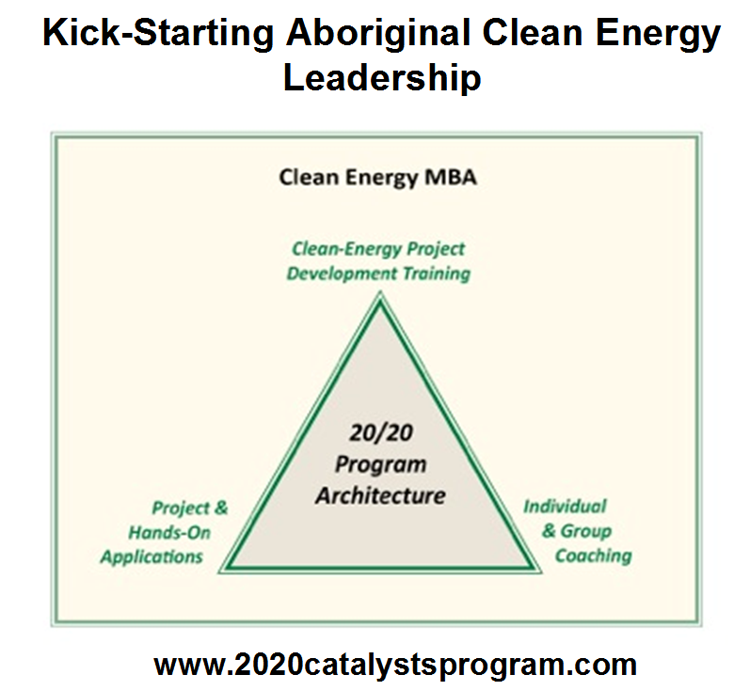

He closed by talking about a four-month intensive Aboriginal Clean Energy 20/20 Catalyst training program. It is intended to start in May 2014. Participation will be restricted to 20 First Nation members or their partners.

Byron Leclair, Director of Energy Projects for the Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation, addressed policy considerations in the same meeting, issues that he believes the people of Ontario need to look at when planning power projects. Pic River First Nation is located along the north shore of Lake Superior in northern Ontario. The north shore is subject to Aboriginal Title Claim, a special title claim where the First Nation is not a signatory of the claim but actual owner of the land. Leclair and his team have interviewed all the members within the community to determine the specific sites that are used for hunting and trapping, along with mapping out cultural and traditional values to develop a deep understanding of their ties to the land. The documentation is supporting evidence for their land claim.

As a developer, Pic River has three operating projects and more under development in both wind and hydro, and most recently transmission. From that perspective, Mr. Leclair finds Aboriginal concerns regarding development similar to those expressed by industry in dealing with government, where clarity is lacking in the regulatory landscape and little is being accomplished. A tremendous amount of uncertainty has been created when it comes to Crown obligations related to consultation. This lack of clarity has had implications for industry, mining and forestry as well as energy.

Ontario has been placed on notice that the Pic River Nation has an Aboriginal Title Claim. Since the claim was filed and perfected in 2001, there have been 4 wind power licenses (7,770 ha), 8 forest management planning arrangements (243,470 ha), 12 new parks (46,560 ha), 1 new national park (40,284 ha), 1,625 mining blocks licensed for exploration, and 13 long term mining leases for 21 years have been granted. In many cases local residents have noticed fences and gates being put in place in these areas, which impede Aboriginal people from accessing their traditional lands.

Mr. Leclair focused on the issue of potential conflict among First Nation communities with differing perspectives on development proposals. He finds the problem has been made worse by misguided government consultation practices. He took a moment to urge his listeners not to take personal offence at his comments. The potential conflict arises largely from the history of overlapping traditional areas, and the exacerbating factor is the policy of trying to involve all communities in projects where they do not naturally have a stake. The result is costly project delays, unnecessary complication and damaged project profitability, he argued.

Pic River's representatives have found that even a well-designed and principled consultation process has different meanings to government, to industry and to Aboriginal communities. Procedural aspects, for example, are often delegated to developers with little regard for the legal principles governing Aboriginal consultation. On the East-West Tie Line, government has instructed developers to consult with fourteen First Nations and four Métis communities, twelve of whom are unaffected by the project, four of them being entirely outside the Robinson-Superior treaty area where the line is to be located. None are even close to the project footprint. It's the Crown's attempt to dodge a very difficult decision that should have been made at the outset, Leclair said. It has given communities with no claim a false expectation to entitlement, IBAs and economic benefit. "The mere triggering of consultation does not mean that you automatically will receive economic benefit from the project," he emphasized.

The purpose of consultation is to identify impact, the purpose of identifying impact is to devise mitigation strategies, and where you can’t mitigate, to identify compensation, Leclair said. In the case of the East-West Tie Line, just six First Nations are affected, but their rights to the economic benefit are being undermined by the government's insistence on consulting everybody. The same policy has resulted in a $30 billion project like the Ring of Fire being held up while the Province trips over itself because of its self-imposed consultation obligation.

Aside from the government's mistaken use of certain principles, those First Nation communities who have been invited into the process despite its lack of impact on them have also been seduced by the prospect of economic benefit, including even Métis communities without a traditional territory in the area. This question of territorial overlap intrinsically creates conflict among First Nations themselves. It is even likely to lead to First Nation litigation against other First Nations making unsubstantiated claims of impact, all to the detriment of projects to the North. The approach should focus on properly informing developers as to whom they actually need to speak with. As for Pic River and the other communities who are actually involved, they need to dialog among themselves in apportioning benefit.

Far too often binding IBA’s are negotiated without proper consultation and participation from appropriate Aboriginal communities, Leclair said. Binding IBA’s should not be negotiated until proper consultation is completed, he argued. But the era of government policies developed in the absence of any First Nation contribution is coming to an end, he said. Pic River has filed an appeal of the Board decision on selecting the developer for the Tie Line, asking the courts to review it.

Mr. Leclair closed the session by inviting everyone to visit the Pic River energy website at www.picriverenergy.com to learn more about their successful energy projects and to see the resources available.

— This article is based on a report written by Kelly Ng with editing by Jake Brooks and Steve Kishewitsch. The images in this article are from the book Aboriginal Power, which is Copyright © 2013, Lumos Energy.