Ontario’s Long Term Energy Plan (LTEP) was released on December 2 and with it a much anticipated round of public attention and debate on the policies and plans that will guide development in the power sector for years to come. However, this round of planning is different from what came before and the response from the public and the industry will require some new thinking and careful consideration of current circumstances, both physical and political.

The LTEP is an ambitious and impressive document. It can potentially set directions and build confidence for the entire economy on a long term basis. However no plan, especially not one as wide-ranging as the current LTEP is, can succeed unless it is used consistently. It needs to have some kind of general support and buy-in from across the sector. In a field with as many divergent players as the electricity sector, and with so many critical connections to other sectors, the active engagement of the full range of concerned stakeholders has become a practical necessity.

The plan itself says that five principles will guide future decisions: Cost-effectiveness, reliability, clean energy, community engagement, and an emphasis on conservation and demand management before building new generation. These are reasonable directions from a public policy perspective, but they are only objectives. In addition to defining objectives, a plan needs to deal with how the objectives will be met. This is where the potential for uncertainty is significant, and some additional detail is important. As a political document, the LTEP goes further than expected in terms of specifying details. However, as a planning document, it leaves a number of details to the imagination.

Establishing principles and managing tradeoffs

When the objectives for a major public initiative are broad and sometimes divergent, a question of principle inevitably arises: How should judgments and tradeoffs be made in cases where a specific proposal serves one objective better than others? If you want to identify coordinated actions that will address all the objectives in a reasonable manner, some of the solutions can be found by asking, what are the key factors that will determine the degree of success that the LTEP will enjoy? Experience shows that three factors will likely rank particularly high on the list: Clarity on the role of regulation, consistency in the expectations for public consultation and coordination with related initiatives.

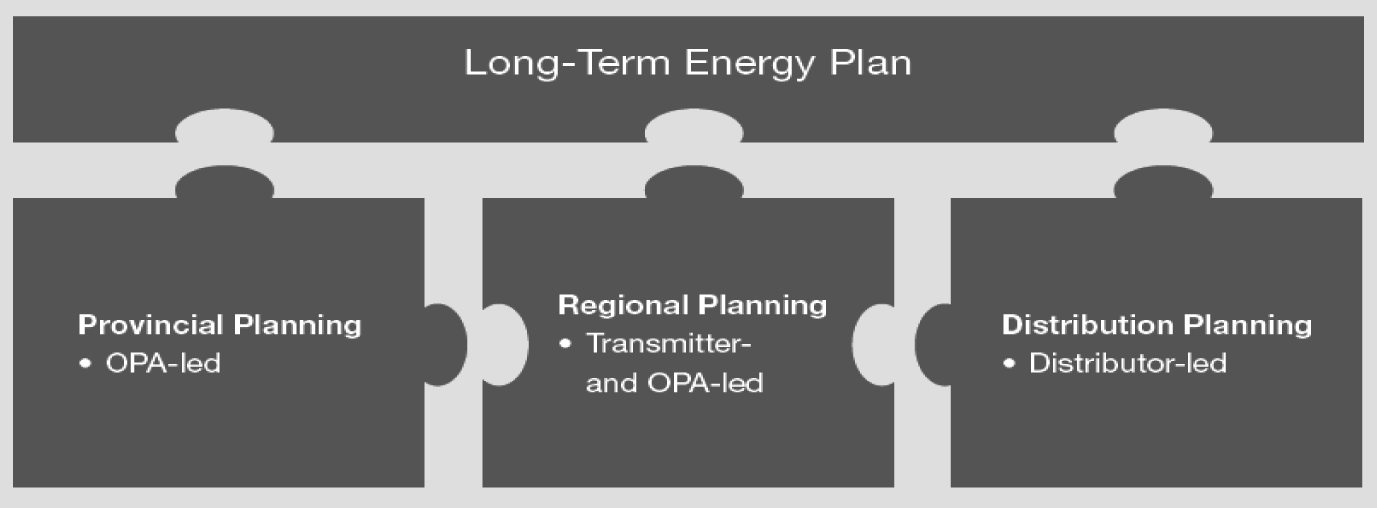

The LTEP contains a fair bit of information on general directions and priorities. But it does not contain all the detail that a reasonably engaged member of the public might want to see. Although many of the specifics are understandably delegated to regional and local plans, much is left unresolved in terms of process and direction, especially considering that this is effectively its third iteration. (Predecessor plans were released in 2007 and 2010.) Two are of concern at a high level: How are responsibilities for implementing the plan being allocated amongst the various players, and who will be responsible for updating the plan in future?

As an example of the first question, on implementation, consider what incentives or requirements would be used to ensure that there is steady progress on the plan. Does the plan establish a complete set of mandates and expectations for various agencies to facilitate its achievement? An energy plan does not over-ride the responsibilities of other agencies to carry out their duties in the area of environment, finance or municipal affairs for example, yet those agencies all have parts to play in implementing the plan. What obligations exist on what agencies to ensure that targets in the plans are achieved? For example, do any particular agencies have any definite duties to resolve local CDM plans, generation siting consultations, permitting/approvals, or construction of connection capacity within specific timelines as per plan? Will the OPA roll out procurement programs and supporting contracts to achieve all the projections? It could be argued that the plan is little more than a carefully crafted wish list unless responsibility for meeting each of the targets in the plan is delegated to a specific entity.

The second question, on updating, is certain to arise before long because supply mix targets always need reconsideration either because forecasts change or development plans go off track. Considering that there will be annual progress reports, to what degree would these reports simply chart progress against goals, rather than actually adjusting the plan? If changes to the plan are to be made annually and on three year cycles, which of the agencies would be responsible for proposing amendments of each type to the plan, or would it be necessary for them to ensure overall coordination by awaiting a revised LTEP from the Minister’s office? More generally, what is the process for updating various elements of the plan, and for keeping it consistent with actual facts on the ground, while ensuring it is perceived as regular and predictable in terms of the update process?

The appropriate role of government

One of the main reasons it has been so challenging to complete any large scale public planning process is that every plan is based on certain assumptions about the role of government. As planning has evolved, the generally accepted concepts about the function of government in this area have evolved with it. In electricity planning it’s almost always reasonable to ask where the boundary should be drawn between the function of the minister’s office and the function of the agencies in making plans. The relevant agencies include, to a greater or lesser degree, groups like the OPA, the IESO, Hydro One, OPG, the electricity distributors, related planning bodies and their regulators. In general the minister should set policies (which the agencies can be expected to accept) and the agencies should prepare detailed proposals (on which the Minister’s office can be expected to forbear in most cases unless there is a serious political consideration the planners overlooked). But here is the rub: how far does public policy reach into the detailed planning process? This is the main area where change and uncertainty creep into the system, and where it’s important to seek clarification time and again, however incomplete the clarification of the day may be.

The understandable desire to resolve big plans is complicated by the uncertainties that are almost always inherent in the social sciences: incomplete consensus, imprecise dividing lines, and continual change. But it is still worth the effort to resolve plans. Billions of dollars in public and private investment turn on these questions every year.

Clarity, consistency, coordination

To improve the effectiveness of the plan a few mechanical adjustments are needed. High among these is to clarify the role of regulation in reviewing and approving plans. Power system plans generated from the policy level of government are relatively unusual in Ontario’s history. But such plans can fit into a reasonable regulatory review process nonetheless. The main difference from what came before is that there would be little or no need for regulatory review of the high level aspects of the plan. As long as the current government’s energy policy is feasible it can be “built into the plan” as one of the working assumptions accepted by the regulator. However the specifics of the plan should not be a matter to be determined by the policy level of government, any more than the licensing of a restaurant, the awarding of a scholarship or the certification of an engineer should be determined by the political level of government.

Agencies, regulators and stakeholders are very good at managing this distinction. There is a large body of experience, both legal and practical, in clarifying what aspects of a plan need to be reviewed and how. Typically, the policy level of government sets overall direction and provides some guidance on the supply mix, often with the benefit of public consultation. Professional planners develop plans that are realistic and reflect the policy directions of government. Regulators review the plans for prudence, consistency and other qualities. It’s been done before in many places. It can be done here, using existing structures and tools.

Another area ripe for attention is the position of public consultation. The government consulted widely before developing the current LTEP and plans a lot of consultation on siting in the future. However there is no clear definition as to what degree of consultation is adequate for the LTEP. Although prior consultation is essential, ongoing consultation is important as well. What’s needed is a set of principles that will determine whether consultation has been adequate at each stage of the process. Not rocket science, but worth some careful thought and explanation to stakeholders. Public consultation is not finished when the plan has been released. Some guidelines would help set the terms and expectations. This is very close to the kind of work the OPA and IESO have made into a major priority in their recent report and recommendations on community engagement.

Finally, what is the expected level of coordination between local plans and provincial plans? Currently this question seems to reside in a relatively opaque area within the OPA – in which the requirements for local plans seem to come from a general concept called a provincial plan. Although there’s general agreement that the LTEP, the provincial plan and local plans all need to be coordinated, it’s not clear which plan sets the specific requirements that other plans must meet, or where the responsibility and authority for follow-through reside in each area. As Ontario’s systems for community engagement evolve, the logic of establishing consistent methods for the integration of community planning with provincial planning will become clearer and more widely accepted. All of the above will help with Ontario’s perennial difficulty: The inevitable need to explain to the public the reasons for cost increases in a political context. Even if there were no green energy plan, the issue would be politicized and the need to explain the origins of the costs and have a conversation about them would continue.

There is a simple fix that will address a good part of these issues: Establish a planning framework that governs planning processes and operates outside the plan itself. The planning framework would be intended to outlast the current plan, and designed to persist through a few changes of government. In fact much of this already exists implicitly or explicitly, thanks in large part to Bill 100. However, LTEP appears to diverge from Bill 100 concepts, and for the purpose of clarity and certainty, the framework could benefit from explicit provisions like these:

a) Who is considered to be the primary author and proponent of the LTEP, the provincial plan, regional plans and local plans

b) What approvals are required for each of those types of plans, and from whom

c) When each type of plan is approved, what has been determined that can not be changed by other plans or processes

d) What the updating schedules will be for each plan

e) What types of public consultation are required in each case

f) What linkages will be necessary to establish between the various types of plans, particularly in terms of ensuring adequacy (where their interactions are not previously defined as in point c)

g) Last but not least: How deeply the current government expects its policies to reach into the substance of the plans.

A planning system with established standards of transparency reduces uncertainty that leads to more market participants, more competition, more innovation and lower return requirements – all of which are tremendously beneficial to Ontario ratepayers and citizens in the long term.

The LTEP is an excellent opportunity to raise awareness, promote debate and foster the development of substantial consensus on energy investments. However government and industry are staking a lot on the success of the plan and it won’t be a slam dunk. It is not enough to simply consult on and release a plan, no matter how well thought-out it may be. The success of a plan depends on active engagement of stakeholders and the implementation of an entire framework of regulatory and policy initiatives. Much as the LTEP represents an important accomplishment, most of the work still lies ahead. To realize its promise the plan will need to be accompanied by major efforts to achieve clarity, consistency and coordination.

— Jake Brooks, Editor