For more than a generation, specialists across the world have been developing and refining a wide-ranging body of knowledge generally known as public participation. The field has played an important role in the formulation of public policy in many places and grown immensely over the years. However with the challenges faced by Ontario in reforming its planning system and ensuring greater public buy-in for new power projects, the scope of professional practice in the area has expanded, matured and taken on new importance – and the tools and techniques offered by its proponents will likely be the subject of increasing attention and careful study.

“Power project developers in Ontario already exemplify strong public participation principles and practices in many cases,” says APPrO Executive Director Jake Brooks. “But there is little doubt that expectations for community engagement are on the increase, and a great deal more will need to be done by developers and planners at all levels working on the electric power system.”

In Canada, a national professional organization known as IAP2 Canada is in place to advance effective public participation practices. IAP2 Canada is the Canadian affiliate of the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), a body that establishes professional standards and produces tools and training programs for experts working the area.

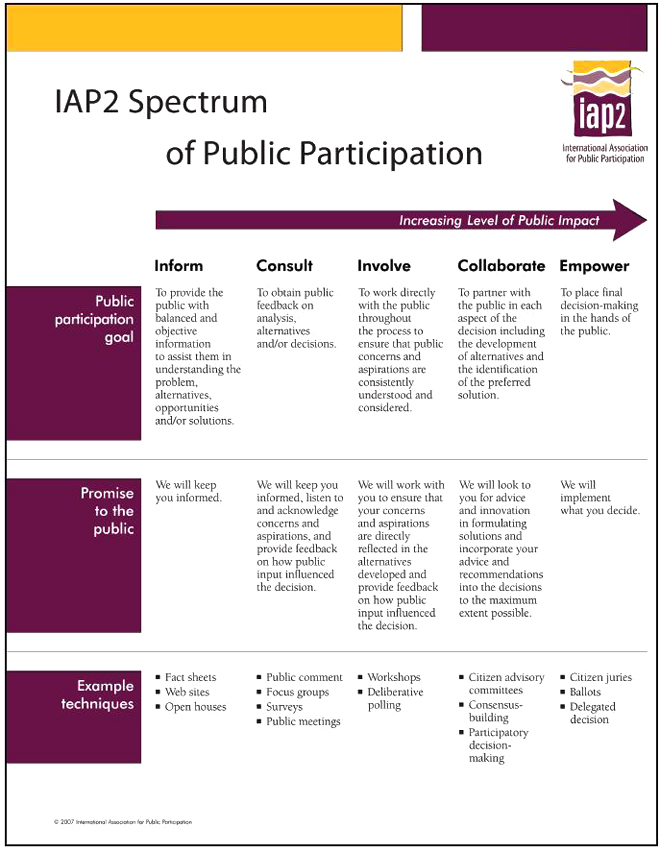

Bob Waldon, a veteran of numerous energy-related development consultations in Canada, points out that IAP2 has developed a number of resources that could be of great value to power project developers and in fact to anyone starting a project that requires community engagement. Chairing the Outreach and Collaboration committee of IAP2 Canada, Waldon says, “These tools and techniques can help developers and communities realize the potential of effective public participation to foster mutual understanding and address key issues in collaborative ways.”

IAP2 Canada represents a community of 500 public participation professionals. In its July 2013 submission to the Ontario Minister of Energy regarding the Regional Planning and Infrastructure Siting Dialogue, IAP2 Canada stated that “no one planning mechanism or siting process can address the dynamic and complex environments in which the decisions on energy planning and infrastructure siting take place. As a result, focusing on sound public participation practice fundamentals is even more important to decide how to proceed with each case.”

The submission noted that whatever participation mechanisms or processes are used, they will need to reflect case-specific elements that include:

• Characteristics of the electricity plan/energy infrastructure, such as Schedule, Complexity and Controversy.

• Characteristics of the affected and involved parties, such as:

• Capacity, mandate and willingness to participate

• Modalities for information sharing and communication

• Values – things that sustain a community or organization and will be protected by them

• Interests – things that move a community or organization forward, and are the key to finding common ground and collaborative solutions.

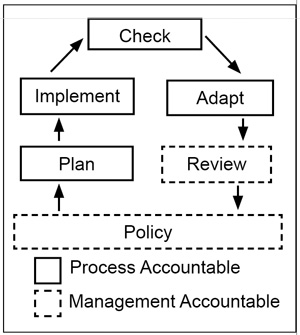

It also recommended a policy approach: “Development of a public participation policy guideline would further position OPA and IESO to more effectively implement their public participation programs using a management system approach (see Figure 4). This would formally support appropriate adaptations during participation programs, and ensure learning from one experience is applied to the next.”

One of the more intriguing resources distributed by IAP2 Canada is a “Public Participation Toolbox,” a document that outlines a broad range methods for public consultation, and considerations relevant to each option. It covers such options as Task forces, focus groups, deliberative polling, field trips, town meetings, web meetings, symposia, hearings, advisory groups, and much more.

Examples of highly creative processes are also included. For example, under a technique known as “Fishbowl Processes,” (a meeting where decision makers do their work in a “fishbowl” so that the public can openly view their deliberations), the toolbox explains that, “the meeting can be designed so that the public can participate by joining the fishbowl temporarily or moving about the room to indicate preferences.” Its benefits include transparent decision making and the fact that decision makers are able to gauge public reaction in the course of their deliberations. However, it also notes significant risks. For example, if the roles and responsibilities of the decision makers and the public are not clear to everyone, the process may not yield the hoped-for results or worse, could lead to frustration among participants.

In another example, the toolbox examines a technique known as “Future Search Conferences.” Such events focus on the future of an organization, a network of people or community. It can involve hundreds of people simultaneously in major organizational change decisions where individuals are experts. It can lead to substantial changes across entire organization. However such initiatives are logistically challenging and it may be difficult to gain complete commitment from all stakeholders. The toolbox is available for free online through the address shown below.

IAP2 Canada promotes “core values” or guiding principles to bolster the integrity and consistency of public participation processes when they are used in Canada. The “Core Values for the Practice of Public Participation” are as follows:

1. Public participation is based on the belief that those who are affected by a decision have a right to be involved in the decision-making process.

2. Public participation includes the promise that the public’s contribution will influence the decision.

3. Public participation promotes sustainable decisions by recognizing and communicating the needs and interests of all participants, including decision makers.

4. Public participation seeks out and facilitates the involvement of those potentially affected by or interested in a decision.

5. Public participation seeks input from participants in designing how they participate.

6. Public participation provides participants with the information they need to participate in a meaningful way.

7. Public participation communicates to participants how their input affected the decision.

The international affiliate, IAP2, says that its focus on practical tools and best practices has made it “the primary resource for developing public participation processes.” It offers a certificate in public participation, educational seminars, and has published its own statement of core value and code of ethics.

No doubt there will be more players entering the field of public participation in the near future, and resources of this nature will be increasingly valuable.

See also the following related stories in previous editions of IPPSO FACTO:

• The greening of community power

• Agencies propose techniques to enhance community engagement in power planning

• Portlands Energy Centre sets a high bar for community relations

• OPA launches procurement consultation in midst of LTEP review

(all from September 2013), and

• Major study likely to raise the bar in stakeholder engagement, October 2007.