By Stephen Kishewitsch, with introduction and files from Jake Brooks

Community-based power generation, a key part of the Ontario government’s energy policy, appears to be undergoing significant re-working. In addition to providing considerable incentives for community and Aboriginal organizations to become project owners and developers under the FIT program, the Ontario government is also encouraging communities to become more engaged in local power planning and development issues.

The latest iteration of Ontario’s Feed-in Tariff (FIT) program provides special priority to qualifying community and Aboriginal power projects, to ensure they are at the front of the line for new power contracts. Power projects that meet certain criteria for community ownership are eligible to earn extra income for the power they produce. Added to this, recent announcements from Ontario’s new Premier Kathleen Wynne and Energy Minister Bob Chiarelli have made it clear that the province is looking to step up the role local organizations play in energy planning, in particular with respect to the siting of new generation projects. “It appears that the emphasis on community engagement in power generation has never been greater than it is today,” says APPrO Executive Director Jake Brooks.

However it is also apparent that the province’s core program for community and Aboriginal power generation is giving industry observers cause for careful reconsideration as the program moves from its early stages towards maturity. Advisors within the policy arms of government, as well as many players in the field developing or considering new community-based generation proposals, are clearly considering what can be done to improve the level and quality of community engagement in power projects in Ontario.

Although the OPA uses the terms “community controlled” and “community participation” in classifying certain projects under the FIT program, the program rules do not refer to community power per se. For the purposes of this feature, the term “community power” is a blanket concept intended to cover a range of initiatives both within the FIT program and outside it. There is also a Community Energy Partnership Program (CEPP), referred to below.

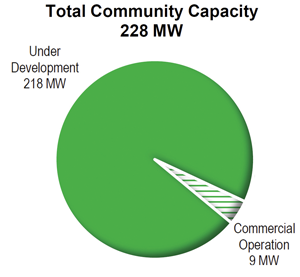

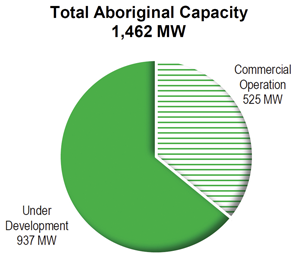

As of March 31 of this year the OPA had finalized 1,706 contracts for large and small FIT projects, with a total capacity of 4541 MW. Of these, 228 MW are listed as community participation, (see pie charts above). 1,462 MW are listed as having First Nation and Métis participation, a large proportion of which includes projects with a minority of community ownership like the Moose Cree participation in the Lower Mattagami redevelopment by Ontario Power Generation. MicroFIT projects are not eligible for community power status under OPA programs, because they are not prioritized by applicant type but many community organizations are in fact sponsoring microFIT projects. Renewable energy co-operatives are also eligible participants. Under the microFIT program, the OPA had 15,550 microFIT solar contracts totaling 136 MW, as of the end of March.

As of March 31 of this year the OPA had finalized 1,706 contracts for large and small FIT projects, with a total capacity of 4541 MW. Of these, 228 MW are listed as community participation, (see pie charts above). 1,462 MW are listed as having First Nation and Métis participation, a large proportion of which includes projects with a minority of community ownership like the Moose Cree participation in the Lower Mattagami redevelopment by Ontario Power Generation. MicroFIT projects are not eligible for community power status under OPA programs, because they are not prioritized by applicant type but many community organizations are in fact sponsoring microFIT projects. Renewable energy co-operatives are also eligible participants. Under the microFIT program, the OPA had 15,550 microFIT solar contracts totaling 136 MW, as of the end of March.

Adding to these numbers, the OPA announced on July 3 that it had approved 951 additional contract offers representing 146.5 MW under the small FIT program. The contract offers announced July 3 include 64 under the community power set-aside, for a total of 15.6 MW; and 85 under the Aboriginal (First Nation and Métis) set-aside, for a total of 15.865 MW. There were 72 projects outside the set-aside but with community “points”, totaling 12,263 MW; and 134 with Aboriginal points, totaling 28,678 MW. (Data were transcribed manually from the published list to an Excel file; transcription errors are possible.)

Ontario’s current efforts to rethink its community power program can be placed in a historical context. For most of the 20th century, Ontario was a world leader in public power, built in large part on a diverse sector of municipally-owned distributors, and Ontario Hydro, which was for much of its history amongst the largest publicly owned companies anywhere. This concept of community power appears to be giving ground to a definition that sees a diversity of players in the community power field, with a variety of mechanisms for instituting responsibility to their local communities. Considering the scale of Ontario’s current community power set aside, which appears to be amongst the most ambitious in North America, it might be said that Ontario has gone from being a world leader in community power through public ownership to being a North American leader in new forms of community power through local engagement.

Other jurisdictions have launched community power programs similar to Ontario’s. Nova Scotia’s program for example has given rise to a wind farm in Tatamagouche with 286 owners under a community co-operative structure.

A diversity of projects and proponents

In Toronto, one of the more successful community power initiatives is known as SolarShare. An initiative of the TREC Renewable Energy Co-operative, SolarShare currently owns 750 kW of solar energy capacity on the grid, and has projects under development that are expected to reach 5 MW. The total will make the 500-member co-op the largest cooperatively owned independent power producer in Canada, it said in a news release July 8.

According to Kristopher Stevens, close to 100 renewable energy co-ops have been created thanks to the enabling Green Energy and Green Economy Act. A full list of current coops can be found on the Financial Services Commission of Ontario website including many that are focused on renewable energy: (http://www5.fsco.gov.on.ca/co-op/Default.aspx).

Other notable examples of community power projects can be found on the website of the Community Energy Partnership Program (CEPP). The following list includes groups or individuals who received CEPP funding to get started, then received a FIT 1 contract and are generating income from their facility:

• FedSol, a 250 kW PV installation on a pair of poultry barn rooftops, owned by Donna and Harold Feddema in the Grimsby area in southern Ontario

• Poulettes Sky Pullets Inc., a similar project, 100 kW in size, jointly owned by three neighbours in a farming community east of Ottawa.

• The Boys and Girls Club of London Ontario, with a 138 kW rooftop PV installation.

• The Strathroy Middlesex General Hospital Foundation, a 250 kW rooftop PV installation.

• Receiving funding from the Aboriginal Renewable Energy Fund (AREF) rather than CEPP was the 4MW Mother Earth Renewable Energy (MERE) wind project, 100% owned by the M’Chigeeng First Nation on Manitoulin Island. (Photo on previous page, and see the October 2012 issue of IPPSO FACTO.) Six others are 50% or 51% owned by First Nation communities.

Among the recipients of a contract offer under FIT 2, in the July 3 announcement, are:

• the Zooshare biogas co-op, set up to generate energy from animal waste at the Toronto Zoo.

• Amber Energy Coop, which has been offered 17 contracts under FIT 2, between 30 and 500 kW.

• The school boards in the districts of York, Simcoe, Toronto (with 310 offers) and Waterloo.

• See also the photos below for more examples.

Recent program changes

The government’s review of the FIT program resulted in a number of changes for community power when FIT 2 replaced FIT 1. Further changes followed when the Minister’s directive of June 12, 2013 was released. (See “Community Power: Effects of the Ministerial Directive of June 12 ,” elsewhere this issue, for a summary.)

One major change was the removal of large projects (greater than 500 kW) from the FIT program, though it appears that community power will play an important, yet unclear role in medium and large procurements going forward. Community Power projects now must apply under the Small FIT program, which includes projects from 10 to 500 kilowatts. (For photovoltaic installations, which comprise the vast majority of community power applicants, this means 600 kW in direct current, on the panel side of the inverter, before the power goes out to the grid.) Facilities up to 10 kW remain, as before, in the microFIT category. These are open to qualifying individuals and various organizations, but not businesses.

One major change was the removal of large projects (greater than 500 kW) from the FIT program, though it appears that community power will play an important, yet unclear role in medium and large procurements going forward. Community Power projects now must apply under the Small FIT program, which includes projects from 10 to 500 kilowatts. (For photovoltaic installations, which comprise the vast majority of community power applicants, this means 600 kW in direct current, on the panel side of the inverter, before the power goes out to the grid.) Facilities up to 10 kW remain, as before, in the microFIT category. These are open to qualifying individuals and various organizations, but not businesses.

In addition, on June 12 the OPA was directed to revise the Small FIT program to also provide municipalities and public sector entities with incentives, similar to incentives provided to communities. In fact, the broader public sector – municipalities, universities, schools and hospitals – are expected to constitute a significant subsector of the province’s community power contracts going forward. Not-for-profits and charities have not been re-recognized.

Between December 14, 2012 and the following January 18 the OPA opened an application window for proposals under the Small FIT category, under the FIT 2 program, for up to 200 MW of capacity. As described in the story on page 21, more than 4,000 applications totaling over 825 MW were submitted during this window resulting in 951 contracts, representing 146.5 MW of capacity, announced on July 3.

The CEPP has also been revamped. Going forward, it appears that funds will only be made available after initial project development stages are complete. Unlike previous iterations of the program, there will be no seed funding or funding for soft costs, considered an important resource for new forming community groups. There is currently no application process available, presumably because the OPA is working on a re-release. It is certainly possible that further changes will be apparent when the process is restarted.

The Ministry and the OPA comment that, given the recently announced changes to the FIT program, the CEPP and the AREF have been adjusted, at least until the province announces details on a new competitive procurement process for large renewable energy projects (over 500 kW). In the meantime, funding for community and Aboriginal projects less than 500 kW will remain available. However, for projects larger than 500 kW, applications are no longer being accepted for the Pre-FIT Organizational Development stream of the CEPP or under AREF, which provides funding to eligible applicants for costs associated with developing a renewable energy project .

Reviews and reactions to recent changes

Reaction among the community organizations to the latest changes has been mixed. On the one hand, old hands in the community power sector fully appreciate what the FIT program, in its earlier and present incarnations, has done for the sector. Significant amounts of projects have been built, and under FIT 2 the proportion of projects with community participation has increased dramatically.

Reaction among the community organizations to the latest changes has been mixed. On the one hand, old hands in the community power sector fully appreciate what the FIT program, in its earlier and present incarnations, has done for the sector. Significant amounts of projects have been built, and under FIT 2 the proportion of projects with community participation has increased dramatically.

Second, as TREC Executive Director Judith Lipp acknowledges, “We’ve evolved over the past eight years, and each time we make some improvements, so government policy is on the right trajectory.” In addition to the growth of coops developing and owning projects, a second tier of organizations – service coops, umbrella organizations and other service businesses – has grown as well (see “Structure of the renewable energy co-op sector,” elsewhere this issue).

On the other hand, concerns are being raised about both the design and implementation of the community power program. Several aspects of the current policy are seen to be problematic among activists in the sector.

First, there has been concern about the effective removal of wind power from the FIT program. As one major consequence of the latest policy, the 500 kW limit under the FIT program effectively excludes the most economic wind projects – considering that the minimum size of a new commercial wind turbine is approaching 2 MW. In the view of a number of industry participants, this constitutes a degree of abandonment of the entire purpose of a Feed-in tariff program:

“Ontario did a bang-up job, the most sophisticated attempt at feed-in laws in North America.” That’s what international wind consultant, former executive director of the Ontario Sustainable Energy Association, Paul Gipe, said in a phone conversation, speaking of the original feed-in tariff program. But in response to Energy Minister Chiarelli’s removal of large wind projects from the FIT program, Gipe wrote, “There’s no sugar-coating [it]. … It’s a bitter setback for all renewables advocates in North America, but an even more stinging defeat for those who believe feed-in tariffs are not only the most cost-effective renewable energy policy but also the most egalitarian, allowing all players to participate in the renewable energy-revolution – not just a few multi-national companies.”

“Ontario did a bang-up job, the most sophisticated attempt at feed-in laws in North America.” That’s what international wind consultant, former executive director of the Ontario Sustainable Energy Association, Paul Gipe, said in a phone conversation, speaking of the original feed-in tariff program. But in response to Energy Minister Chiarelli’s removal of large wind projects from the FIT program, Gipe wrote, “There’s no sugar-coating [it]. … It’s a bitter setback for all renewables advocates in North America, but an even more stinging defeat for those who believe feed-in tariffs are not only the most cost-effective renewable energy policy but also the most egalitarian, allowing all players to participate in the renewable energy-revolution – not just a few multi-national companies.”

Mr. Gipe went on to acknowledge that “Ontario is entitled to a hiatus to take stock of their program. They’ve done more than any other Canadian province and more than most US states in developing non-hydro renewables. ... We took two steps forward in Ontario. Now we’ve been forced to take a step back. That’s still progress.”

Independent consultant Marion Fraser, a power sector expert with lengthy experience in various provincial Ministries, said in an email, “The opposition to wind farms stems primarily from the large scale farms dropped into farmers’ fields with little or no benefit to the local community. ... The Green Energy Act was intended to change that and enable communities to develop their own resources. There are a few good examples such as Brant County and M’Chigeeng First Nation on Manitoulin Island and solar installations on farms, churches and schools. In these cases the revenues and profits will stay where the resource is. But by and large, the recent changes to the FIT program demonstrate a bias for big projects and a willingness to sell our natural resources (wind, sun, water) to non-Ontario residents.”

Judith Lipp, Executive Director of the Toronto Renewable Energy Coop (TREC) and a board member of the Federation of Community Power Cooperatives (FCPC) (see “Structure of the sector”), noted, “The whole reason the community power movement got behind the FIT program was that we could not compete in a tender process. You could structure a competitive tender process in a way that favours community, but then you’re getting so prescriptive it becomes micromanagement.”

In a statement issued June 20, TREC said, among other things, “The retraction of FITs for large renewable energy projects is a huge concern to TREC. FITs are a policy for which the community power sector has fought for over 8 years and is still seen as the most equitable policy for (renewable energy) procurement that enables broad participation. The details on the competitive procurement are vague and until more clarity is provided we remain skeptical about the efficacy of this decision. In addition, we are uncertain why the goals of a competitive procurement process cannot be satisfied through the FIT program. Our [20 megawatt] LakeWind project is potentially compromised again (9 years running) by this shift in policy as we may again be competing on criteria that do not reflect the strengths that co-ops and community ownership can bring to a wind project.”

Harry French, a board member of the Ontario Co-operative Association, President of Ontario Sustainability Service (the Community Power services arm of OSEA) and President of the Whitechurch Stouffville community power co-operative, commented, “Energy prices in Europe are five times what they are here. I don’t think people on this side of the Atlantic fully appreciate what kinds of changes we’re going to need in our energy regime. … [It’s true that] the private sector didn’t do a very good job introducing projects into communities. Now we’re starting to work on smaller, 10MW projects with commercial operators like International Power, with community ownership. There wouldn’t have been as much resistance if we’d started that way. People support what they helped to create.”

Of the Ministry of Energy decision to replace the large FIT program with “a new competitive procurement process to better meet the needs of communities,” Ministry spokeswoman Kirby Dier said, “This new process will require energy planners and developers to work directly with municipalities to identify appropriate locations and site requirements for any future large renewable energy project.

“Other important changes to increase the role of municipalities in renewable energy project development include:

• Providing funding to municipalities to develop Municipal Energy Plans. Municipal Energy Plans will integrate energy, infrastructure, growth and land use planning to support economic development, increase conservation and identify renewable energy opportunities.

• Revising the Small FIT program rules, for projects between 10 kW and 500 kW, to give priority to projects partnered with or led by municipalities.

• We’re also making an important change to ensure that the financial benefit of wind projects is realized by municipalities. The Ministry of Finance will work with municipalities to determine a property tax assessment rate increase for wind turbine towers. We expect to make an announcement this year. This change would apply to existing wind projects.”

Deb Doncaster, Executive Director of the Community Power Fund, confirmed at the end of July that the co-op sector, under the umbrella of the FCPC, is finalizing a white paper that will recommend to the Ministry that an intermediate size of project be made available under the FIT.

“We’re trying to secure more opportunities for community power,” she said. “We’re suggesting that there be a medium-size FIT, between 500 kW and the 10 MW, and that they use the FIT to procure it, and save the RFPs for projects over 10 MW. We’re also suggesting a target of 500 MW for community power, including coops, municipalities and Aboriginal groups by 2017. There would still be a point system, but no setasides [for that size of project – setasides would still apply to small FIT]. The point system would be based on community benefits, which could range from community ownership, to local community improvement funds, to collective land-lease agreements, anything the community defines as being a benefit.”

TREC also expressed concern that a wider range of organizations are now able to compete for capacity within the 150 MW allocated for Small FIT projects for each of the next four years: “While we support the inclusion of the MUSH sector in RE (renewable energy) activities, the further slicing of the community power pie leaves us worried about what is left for the co-op sector and how well we can compete against better-resourced participants. We know from experience that co-ops provide the greatest opportunity for direct community participation in the form of investment and also a democratic organizational structure, but enabling that level of inclusion also means the co-op model is more cumbersome and costly to implement. This makes it difficult to compete against commercial and municipal players. With momentum finally beginning to build in the co-op sector under the FIT 2.0 rules, we are concerned about the implication of the FIT 3.0 Directive for many of our co-op colleagues.”

The response of organizations that work with community and commercial groups has also been critical in a number of respects.

• “Some 70% of applications were rejected simply for being incomplete, many of them aboriginal and non-aboriginal projects”, OSEA notes. Research for this feature revealed, as a universal experience among those interviewed, that beyond a formal statement, no detailed reasons were offered initially by the OPA for the ruling of incompleteness. In more than one case, out of two virtually identical applications, one would pass the completeness test and the other would not. Applicants naturally would like to know what the applications’ shortcomings were, so that they can amend the application when they reapply during the next window opening – if possible, without losing their place in the queue.

• A related experience was applications rejected for incomplete site access. Many speculate that those with detailed land leases were rejected, while those with simple sign back letters (which will later need to have a formal lease put in place) received the green light. Here again, some applicants who believed they had been diligent in securing site access are unclear as to the reason for rejection. Again, some cited virtually identical applications, one of which passed site access and another that did not.

OSEA’s Executive Director Kris Stevens expressed the concern that the FIT program and its associated Renewable Energy Approvals process, both intended under the Green Energy and Green Economy Act to be a streamlined process without the complexity and high entry costs of RFPs now actually takes longer than it used to. “Japan has built as much new solar power in a single year as Ontario has done in four and no new contracts have been issued for over two years,” he observed.

Responding to the issue, Shawn Cronkwright, Director of Renewables Procurement at the OPA, explained that this was a necessary consequence of the change in the FIT program, from its first incarnation to version 2.

“In FIT 1 people applied on an ongoing basis, and weren’t really competing with anybody else. As long as there was capacity [on the lines] you could succeed. There was no specific target. This time around, knowing that we had a few thousand applications competing for a scarce resource, we had to make sure the rules were such that we could compare them. We said repeatedly up front that, because there was a competitive element to this, and because we knew there would be more than would be successful, to be fair and consistent to everybody, it wasn’t going to be the same as FIT 1. People had one chance to get it right – there was no opportunity to correct mistakes midway. In fact we did a webinar, two or three days after the window opened on December 14, where we went over the requirements, and specifically where things had changed between 1 and 2. I think the difference is, it doesn’t really sink in until it happens.”

Cronkwright pointed to one of the likely sources of frustration over what many applicants found to be minor administrative reasons for rejection: “Company names are critical to get right. ABC Inc. may be a legally separate entity from ABC Limited, even if you’re dealing with the same people. It may seem like a minor matter but it’s not.”

The OPA reports that it did in fact send additional details to each applicant on why an application failed the initial completeness and eligibility reviews, though some applicants still feel they would have liked more. In any case, all unsuccessful applicants will have an opportunity to submit a new application during the next small FIT application period, expected in the fall of 2013. They will not, however, retain their original place in the queue. To be more specific, while FIT 1 projects remained in a queue for FIT 2 and could retain their time stamp if they re-submitted under the FIT 2 window, unsuccessful FIT 2 applications do not remain in a queue. “The program has evolved, and there’s no resident queue,” Cronkwright said.

The OPA held webinars on July 8, 9 and 15 to review those program requirements and discuss the most common issues encountered during the application review. While apparently a proportion of the time was taken up with expressions of simple frustration, Mr. Cronkwright says he was satisfied with the outcome.

“There were good points raised, and lessons learned on both sides. We’ll continue to discuss how we can work together to improve the process. We’re looking at ways to improve our process and make it easier. On the flip side, we ask applicants to make sure they’re reading things carefully. I’m pretty sure we’ll have a higher success rate going forward.”

See “Community Power: Common issues leading to application incompleteness,” elsewhere this issue, for a summary of some of the most common and most frequently occurring issues discussed during the webinars.

• The scale of the 25 MW worth of capacity for the community power set-asides. There were 457 applications submitted, representing 85 MW of capacity, for that 25 MW set-aside. Overall, there were 825.6 MW worth of applications submitted, for the 200 MW being allocated under the Small FIT program. OSEA had recommended a 500 MW set-aside just for community power.

Judith Lipp observes, “There needs to be a volume of activity that co-ops can anticipate, because of the scale issue. If you’re only getting one contract this time around, and you’re putting in a lot of investment getting your co-op set up, you need to know that there’s a pipeline that you can count on, at least up until you’ve reached your scale. That’s what’s problematic about these small targets, the lack of transparency in the process. The uncertainty needs to change for this sector to be robust. The elephant in the room is the LTEP. Unless we see more commitment to renewables, all this could go away. We do need those targets.”

On the size of the annual allocation for Small FIT projects, 200 MW overall and 25 MW for the community setaside, community organizations not surprisingly had argued for a larger number. The Ministry’s response, when asked, was that it was driven by the need to pace the procurement schedule for renewables, while encouraging participation in the program and continuing support for manufacturing and jobs. The figure represents an average of over 800 Small FIT projects per year and an average of over 5,500 microFIT projects per year, the Ministry estimates, as well as 6,400 jobs between now and 2018 and enough new, clean electricity each year for more than 125,000 homes.

In reviewing the Long-term Energy Plan, as the Minister announced in April, the government will “consult on our supply mix, our plan for conservation, and whether we have the right strategies and targets in place at the broader provincial level. We intend to review Ontario’s electricity supply and demand forecast to explore whether a higher renewables capacity target is warranted,” Ms. Dier said.

• The availability of funding under CEPP, which has been redefined, at least as participants in the co-op sector see it, in a manner less suited to the early stages in setting up a co-operative or to support the administrative costs in developing a project. As Lipp commented, “Co-ops are eligible for up to 50% of their legal costs in preparing the offering statement, but nobody does an offering statement unless they know they have a contract. The first thing you’re going to do is a proper business plan, hire a business manager, hiring consultants, and so on. That’s what the early money should do. [The revised funding program] will cut back on the number of applications. There might be groups who don’t even bother getting started.”

OSEA Executive Director Kristopher Stevens has suggested, “Converting the CEPP into a forgivable loan program would make a lot of sense, since community projects once they secure a FIT contract are a business capable of repaying the funds that they needed to get up and running. Later stage financing is helpful, but it is really the initial seed money that is key to help local folks get organized to develop or partner on projects.”

Deb Doncaster, executive director of the Community Power Fund, which managed the CEPP from 2009 – 2012 and who campaigned for a source of early funding, is now starting up Community Capital, a fund to make bridge loans to coops.

The OPA comments that there will be new rules for CEPP for projects larger than 500 kW, once there is more information about a new procurement process for large projects.

After the completeness test for applications, there was also the “TAT & DAT” test for connection capacity availability, which unfortunately had to weed out some further projects for which there would have been no room on distribution lines, or at transfer stations to the transmission grid. Partly as a result, there was only one project accepted east of a line between Ottawa and Brockville.

On this matter, Mr. Cronkwright explains, “There’s all kinds of ongoing work at the distribution level, and at the transmission level there are things like a transformer station where upgrades have been identified, but may still be in process. We proactively reach out to all the transmitters and distributors just before we open a window, to get the best info available, and use it for the testing cycle. We’ll acknowledge the contracts we just offered, we’ll acknowledge any other procurement activities or contract management in the next few months. When we open the next window, that information will be updated to reflect what we know and what the transmission and distribution utilities have done in the meantime [so that the TAT and DAT tests will be using the latest information].

“The process requires a lot of cooperation, and we’ve found that all of these folks are extremely co-operative, and there hasn’t been an issue at all, and that’s due to the good relationships on all sides.”

Of the entire success rate for this round, and whether 951 contracts out of 3,938 applications is a lot or not enough, Cronkwright observes, “We have an existing infrastructure, wires and so on, that is going to take some time to update. So some of the types of solutions that seem readily deployable in other places like Europe – I think some of those are goals for Ontario, but all of that transmission and distribution infrastructure is going to take some time to catch up. The challenge right now is how do we encourage small generation on the system we have. It will probably never evolve as fast as some people would like, but there’s still a strong commitment to small and micro projects. We certainly support them, but we’re all still dealing with the legacy infrastructure.”

The back story

There is a widely shared acknowledgement that community-based power is attractive because it distributes the benefits locally and builds local support and social license. Based on the amount of commercial and community interest and the generation capacity under construction it appears that the FIT program is effective. Yet at the same time some are asking why it has taken more than two years for the FIT review to be completed and new large FIT contracts to be released. Community and commercial proponents of all sizes, as well as manufacturers who have made significant investments in the province, will inevitably look at how community-based projects and community-commercial partnerships are driving the market in places like Germany and Denmark and wonder what is going on in Ontario. Some concern has been expressed, in view of the substantial cost in time and money attached to setting up manufacturing facilities and developing projects (especially for smaller community proponents), that Ontario may soon see an increase in industry and developers dropping out of the market unless contracts are forthcoming. Research for this article found, anecdotally, that this is already happening. “Expecting companies and communities to go without any new business for two years is problematic,” Stevens says. “To then constrain the amount of project capacity significantly compared to the earlier promise of the program has great potential to damage Ontario’s reputation as a good place to invest.”

Stevens predicts that, “We are likely to see a requirement for community participation in all or nearly all projects under future procurements. We are also going to see community members, municipalities and First Nations rapidly become sophisticated participants in the sector who demand higher standards from those who build projects in their backyards, as well as becoming proponents themselves and savvy partners for those in the private sector.”

Some stakeholders will likely struggle with the challenge of simultaneously meeting political, business and economic objectives. Political and business imperatives drive proponents to sharpen the developer’s accountability and enhance the net benefit to their project hosts and partner communities. Shareholder profit maximization is of course essential for financing. And finally, if procurement is to be considered successful in the long term, the program must ensure that power generation capacity is procured in an economic fashion that protects ratepayers and tax payers from cost overruns and other hidden costs.

Without proper attention to local engagement, developers may face frustrated communities slowing down the timeliness and orderliness required for businesslike procurement. Or worse, projects may even be stopped or forced to move. Doing things right the first time is always cheaper, even if it take a little longer then desired, compared to having to do things all over again with your hosts angry and upset.

No doubt there will be a lot of public and private conversations about what’s worked and what hasn’t worked in the field of commercial and Community Power in the months and years ahead.

Those who watch the development of regulatory systems in Ontario are likely posing their own related set of questions. For example, if the form and depth of community involvement in the development of new power projects is to be formally and informally stepped up, what kind of changes to the regulatory and planning processes will then be necessary? (See “Regional planning: APPrO recommends more explicit transmitter obligations to support scoping process,” elsewhere this issue, for a story on changes that are under consideration to the regional planning process in Ontario.)

Conclusions

Considering the rapid summer blitz of public consultations that are underway on community engagement in power project siting, any final conclusions on the role of communities in power generation would be premature. But there is little doubt that Community Power has grabbed the attention of both the public and private sectors in Ontario and that it is poised to grow further, play a wider role, and to mature as the system evolves to reflect the changing expectations of government and the communities who have given rise to the entire sector.

The prospects for communities to become more than hosts by developing, partnering and enabling energy projects in their backyards have never been better.

See also the following related stories:

Portlands Energy Centre sets a high bar for community relations

951 Small FIT contracts approved

Structure of the renewable energy co-op sector

Common issues leading to application incompleteness

Ontario’s three forms of incentives

The Feed-in Tariff program timeline

Types of eligible applicants under FIT 2.0

Effects of the Ministerial Directive of June 12

Community power around the country