By Stephen Kishewitsch and Jake Brooks

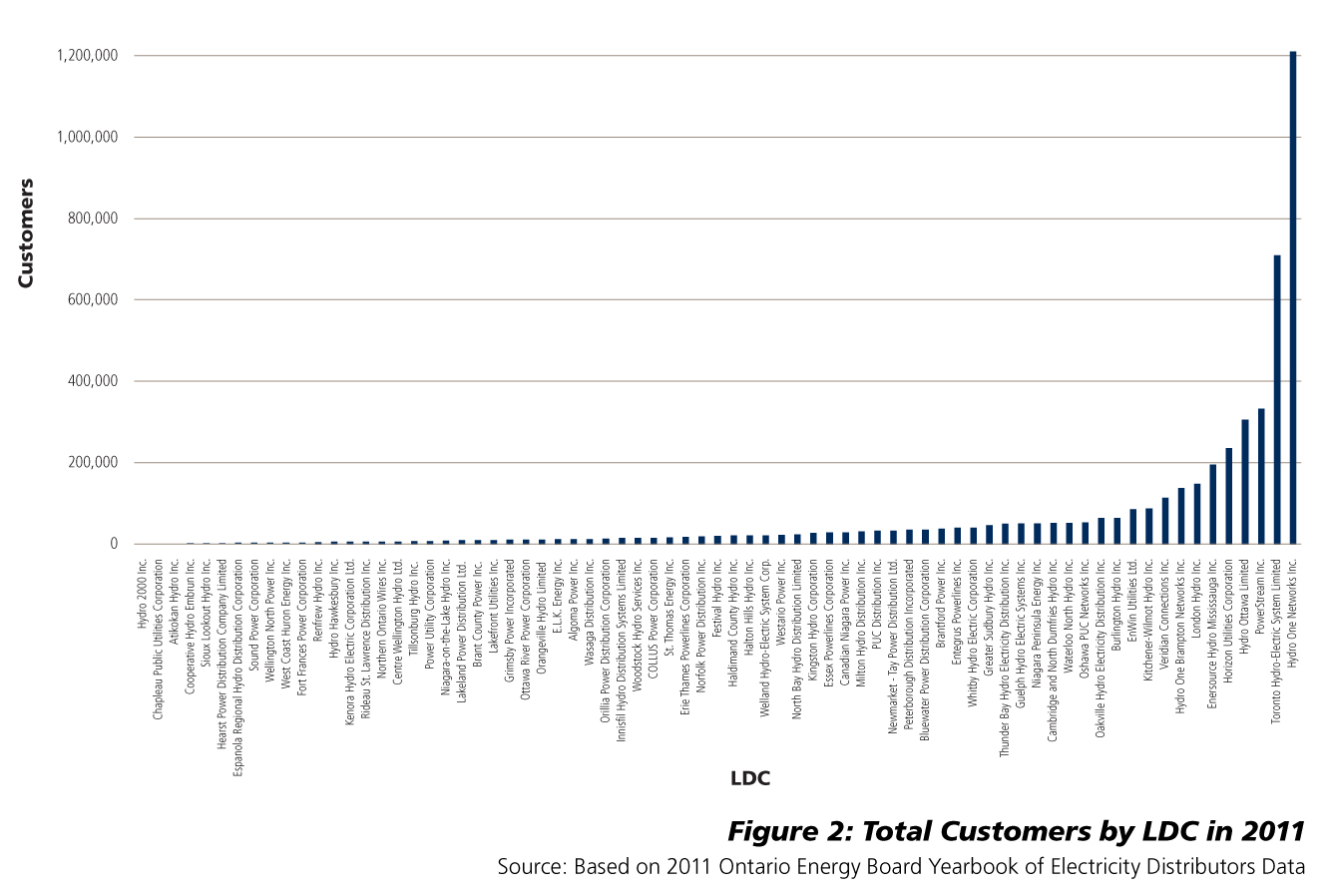

There is widespread agreement that most of Ontario’s electric distributors need to be larger than they are today in order to meet a range of challenges that are expected to confront the sector in the coming decade. Many if not all of the smaller distributors are expected to have difficulties meeting the public’s expectations for new and more sophisticated services in the near future, while achieving higher levels of efficiency in the process. Yet it is expected that the distribution sector will have to manage billions of dollars in new investment over the next decade just to keep its systems operational, to say nothing of upgrading them to meet new challenges presented by the smart grid, electric vehicles and distributed generation. There are a total of eighty electric LDCs in Ontario at the moment, although the present discussion excludes seven of them for various reasons. Ontario is in fact very unusual worldwide in having so many electrical LDCs given its population.

With this in mind the Ontario government convened a blue ribbon panel in April 2012 to provide advice on restructuring the sector. Senior political figures with deep expertise in the energy industry headed up the panel: Former Cabinet Ministers Murray Elston and Floyd Laughren, and the head of Gowlings’ energy practice and former MPP David McFadden.

Expected to lay out a path for reform, the Report of the Ontario Distribution Sector Review Panel was released on December 13, 2012 and immediately provoked divergent reaction from across the power industry. The panel consulted with municipalities, LDCs and the Electricity Distributors Association (EDA), as well as with other energy experts to examine potential savings and benefits available from consolidation, as well as potential risks.

In fact, the proposals for LDC consolidation and reform have brought a series of profound issues to the surface, prompting heated debate reminiscent of the discussions that took place prior to the major restructuring of Ontario’s power sector that was implemented in the 1990s.

The Panel’s main recommendations will by now be familiar to most readers. (See sidebar for a summary.) The following report examines the major aspects of the panel's conclusions. Panel Chair Murray Elston provided further insight in a phone interview, and commentary was provided by the Electricity Distributors Association and several other stakeholders.

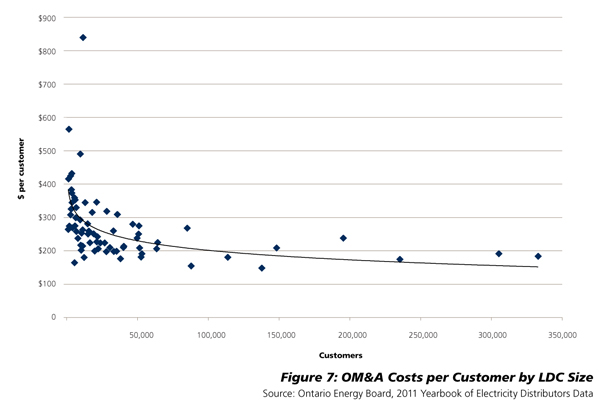

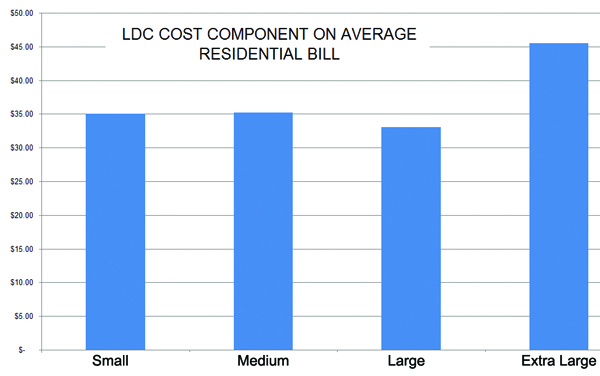

On consolidation, and its expected savings from improved efficiencies and reduced cost to the consumer: “Compared to their larger counterparts, smaller LDCs tend to have higher per capita costs for operations, maintenance & administration (OM&A) [75% higher on average for small than for large LDCs], which are passed down to customers through rates ... . [T]here is a duplication of equipment and facilities among neighboring LDCs, [and] the large number of LDCs also increases the cost of providing necessary regulation.”

The panel report lists several amalgamations, starting in 1999 with the creation of Veridian Connections, and the savings they achieved. The panel foresees savings in net present value of $1.7 billion over the first ten years, or a net $1.2 billion after deducting $500 million in transaction costs. Those targets are enough to drive a whole series of business opportunities, Murray Elston said, in a panel presentation of their report to the Ontario Energy Network January 15.

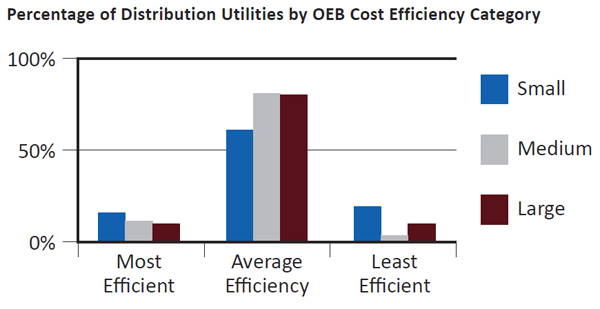

Electrical LDCs in Ontario, who are collectively represented by the Electricity Distributors Association or EDA, tabled evidence during the review showing that strong examples of efficiency and innovation can be found amongst the medium and smaller LDCs. In other words, larger-size LDCs are not always preferable in terms of economics or levels of customer service. (See graph.)

It's often noted that the LDC is the generally the customer's only point of contact with the electricity system, and, at least when the municipality's name is in the utility name, creates a sense of local ownership and loyalty. Concerns have been raised that consolidation might result in a loss of these qualities, and a loss of responsiveness to local conditions and concerns. But in a conversation with APPrO, panel chair Murray Elston said that the panel, in its meetings with close to 85 stakeholders, had in fact asked that exact question. The experience of those utilities that have already undergone some kind of amalgamation has not shown a loss of service quality, he said, in fact have received high ratings from customers. "People with good business skills will in all cases understand the needs of their customers and be able to deliver the best product at the best price, locally," he said, particularly if the utility is run by a majority of independent and professionally qualified board members, as recommended.

For its part, Fort Frances Power, with 3800 customers, claims the third-lowest rates in Ontario. In their submission to the panel, they say there is no correlation between the size of a utility and its overall efficiency and its rates, but rather variables such as geography, physics, history and operating strategy dictate efficiency and rates.

There is in fact a suspicion in some quarters that the panel was working with a preconceived mandate from the government to reduce the number of LDCs in Ontario. Murray Elston rejected this, saying "No. No-one in the Ministry said go away and write a report that talks about consolidation. We were left with a very open slate of possibilities."

Speaking to the January 15 OEN meeting, Floyd Laughren emphasized that he relies on research showing that cost per customer is lower for larger LDCs. “The plural of anecdotes is not data,” he said. He did note that the expected advantages to size – the expected efficiencies, the advantageous access to capital, etc. – would likely materialize over time, rather than immediately following consolidation.

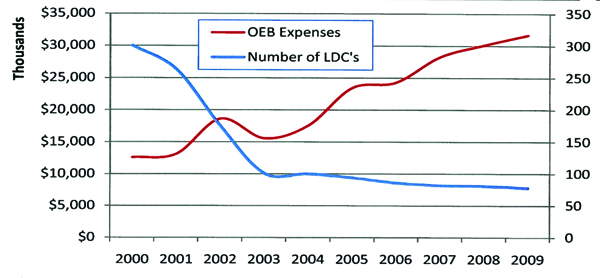

The panel also says that reducing the number of distributors will produce savings for the province in the reduced regulatory burden at the Ontario Energy Board. Smaller distributors question this as well. Joerg Ruppenstein, President and CEO at Fort Frances Power, notes how the OEB's recent Renewed Regulatory Framework for Electricity has proposed to implement simplified reporting and rate submission requirements for the smaller LDCs, sparing them the extra cost of accounting details that are much more relevant to the largest utilities. Niagara-On-The-Lake Hydro offers the following graph, showing the rise in the OEB's expenses to 2009, driven by the regulatory costs for new government initiatives, even as the number of LDCs has decreased.

On voluntary versus mandated consolidation: This is probably the most controversial element in the panel's recommendations. In a December 13 response to the panel's report, the EDA called enforced amalgamation "problematic." ... "[V]oluntary mergers deliver the greatest benefit to customers and communities. Ontario’s distributors have a strong track record of successful consolidations – merging into 75 utilities from more than 300 since 1998 – and recommended removing barriers that exist today that discourage further consolidation. ... The Panel has offered no mechanisms to remove many of the barriers standing in the way of these deals getting done and that’s a glaring omission, especially considering the Panel’s aggressive timeline for these transactions to happen.”

Invited by APPrO to comment further, EDA Chair Max Cananzi added, "Compulsory amalgamations do not offer the opportunity to do the due diligence required to determine if there is a sound business case for the amalgamation."

APPrO asked Mr. Elston whether the panel’s model remains workable, its goals still achievable, if amalgamation were to be entirely voluntary, and pursued on economic considerations alone? His quick rejoinder to this is, "What you’re really saying is, can we let people cherry-pick the more financially interesting territories, and leave orphaned areas behind? You have to deliver to everybody, you can’t leave people stranded. That was one of the elements we had to preserve. We don’t think it will be as viable to have low-density, low-volume customers as holes in the supply system. You end up still having to construct duplicate capital around such systems and not getting as efficient a distribution sector. You have now, on one side of the street, one company’s lines, and on the other side another company’s lines, and you have two sets of trucks on the same route. The more you have of those, the less advantage there is to the capital to keep the system in good repair."

David McFadden adds that, once they'd done with their talking points, in open conversation almost without exception all the small utilities said they’d like to be bigger. Those with 20,000 customers thought they should be in a group with 75,000, those with 50,000 thought they should have 100,000. All admitted they can’t stay the same, and that they preferred to manage the coming change rather than be merely buffeted about by external forces. (See further below.)

On contiguity: As the panel report observes, “[a] number of utilities serve a patchwork of widely separated areas with non-contiguous boundaries. They include for example, Veridian Connections, Erie Thames Powerlines, and Entegrus Powerlines. Fig. 3 {pdf p 11} shows the boundaries of one of them, Veridian Connections. In most cases the intervening territory between these non-contiguous areas is served by Hydro One Networks. ... At the same time, a number of municipalities have multiple distributors serving residents within their municipal boundaries, ... such as Thornton, a village near Lake Simcoe with 1,000 inhabitants, where the service areas of three separate LDCs converge, namely Hydro One Networks, PowerStream and Innisfil Hydro.” Boundaries inhibit the efficient use of capital and resources. Minimizing boundaries would allow rationalizing control facilities, equipment yards, substations and maintenance crew routes.

Speaking at the panel’s presentation to the Ontario Energy Network January 15, Murray Elston said that it was clear from the earliest stages, in discussions with stakeholders, that the model the stakeholders themselves, including the Electricity Distributors Association, had in mind involved contiguous areas. The panel became convinced that cutting down on the number of border areas between the territories of LDCs serving major urban areas, and eliminating spaces between such territories, will remove duplication and result in savings.

Max Cananzi comments, "Contiguous and clear understandable service areas benefit customers in easily identifying their local utility. Contiguous service areas also provide for better efficiencies for field services or maintenance of assets. [But] While contiguity is desirable it is not a necessity in obtaining benefits. Many examples exist in our sector today where LDCs have been able to obtain head-office and administrative savings while maintaining non-contiguous service areas."

Some observers have noted however that there may be cost challenges associated with trying to achieve fully contiguous boundaries with eight regional distributors as contemplated by the panel. Observers have said that labour rates tend to be significantly higher in areas served by Hydro One Distribution. As a result, wherever an urban utility takes over Hydro One territory there could be a sharp increase in labour costs, offsetting the savings achieved by other kinds of efficiencies.

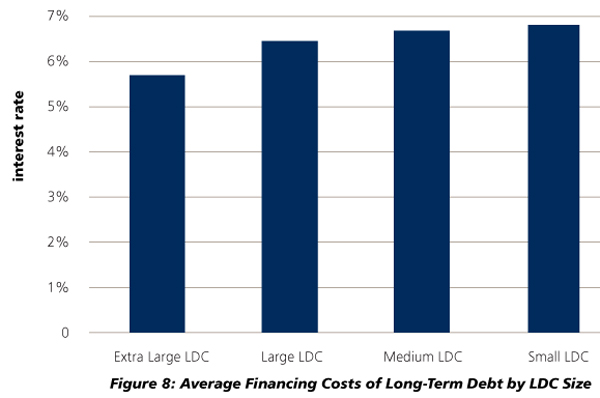

On the ability to find investment capital, not only to maintain and replace existing equipment but to keep up with a changing technological environment, such as the various smart grid applications: The panel quotes a 2011 Conference Board of Canada estimate that $20.6 billion in investment will be needed over the next 20 years, not counting additional investment to deal with distributed generation and the smart grid. The panel says that smaller LDCs generally have access to a narrower variety of capital markets and are typically charged higher interest rates and financing charges, a cost they pass on to customers. The panel argues that the smaller LDCs should be able to turn to private finance, rather than adding to the province’s debt load through Infrastructure Ontario’s concessionary-rate loans, as at present.

And, related to the Panel's further point about the smaller utilities’ ability to keep up technologically: As the panel observes, “electro-mechanical switches that were once the backbone of the transmission and distribution systems are going the way of the typewriter. The future for electricity distribution is computerized and data-driven.” Smart meters and smart homes are just the beginning; there is a wide range of information and control technologies that will be familiar to readers of these pages, allowing system awareness, rapid response to problems, incorporation of distributed generation, and controlling fluctuations in power quality. The concern is that smaller utilities may not have the technical capacity to develop such systems for themselves, and so fall behind in the service they provide their customers. In fact, the panel report says in so many words (page A33): “The innovation seen in Hydro One Networks’ outage app, or Horizon Utilities’ energy mapping cannot be as efficiently developed and utilized by smaller utilities.”

Based on comments from other sources, this issue is perhaps not as clear-cut as it may seem. Fort Frances Power is proud of having developed, on its own, a comprehensive smart grid, GPS-based asset mapping system similar to one recently developed by Hydro One itself. The system has been in place for eight years, said Joerg Ruppenstein, and is used for job planning, automatic creation of work orders, parts replacement, and the like. It also integrates with police and fire services. The utility has also established a cell phone service along the highway as far as the Manitoba border. Fort Frances' service area is limited to the municipality, and entirely surrounded by Hydro One's rural service, with the nearest neighbour 300 miles away. "We're a little gem," says Ruppenstein. "We feel that we've adapted our business to meet the demands of the current industry, embraced new technologies, and we strongly oppose mandated consolidation."

A number of utilities have formed cooperatives and buying groups for specific purposes, to overcome their limitations on purchasing power. Fort Frances, Thunder Bay Hydro, Kenora, Sioux Lookout and Atikokan formed a joint group to implement their smart meter programs, and have formed other cost sharing arrangements for billing and customer information, employee training, legal fees, ESA compliance, and other special project coordination. This kind of voluntary joint effort is the best way to address advanced technology issues, Max Cananzi says, adding, "The EDA’s submission to the panel reviewed over 20 different shared-services initiatives across dozens of LDCs, along with the cost savings. It is an area that should be encouraged further."

The panel itself spoke to stakeholders in one cooperative with eleven LDC members. But voluntary buying groups are a short term solution that won’t do the job in the long run, says Elston. "This simply tells you there is a need for smaller organizations to be bigger. The LDCs have demonstrated they can come together, and deal with the issues of local ownership, of finding new forms of purchasing power. One thing they have not demonstrated is that there’s going to be reasonably priced access to capital for everybody. In the long run we see the biggest overall cost-effectiveness coming from the shoulder-to-shoulder model."

On privatization: As the panel report notes, there is only one private sector majority LDC owner in Ontario, FortisOntario, which owns 100% of three smaller utilities in different parts of the province, and with two investment firms also hold minority interests in a number of other LDCs. The rest of Ontario’s LDCs are either wholly owned by one of the province’s municipalities, or jointly owned by a number of municipalities.

The consulting firm Power Advisory LLC has published a commentary on the panel’s recommendations, in which they offer the opinion that private sector participation is “absolutely essential” to modernizing and transforming Ontario’s distribution sector, along with the panel’s other objectives. The changes are needed to allow the sector to compete with other industries for the needed capital, they argue.

David McFadden acknowledges that there is a lot of reluctance over privatization among LDCs. Accordingly, the panel felt it would be helpful if Ontario-based pension funds made the first moves in that direction. He provided the example of the Toronto District Heating Corporation, as it was at the time: "effectively bankrupt" in the late 1990s – owned by governments and hospitals, none of whom could or would put any capital into it. Spearheaded by Jack Layton, the City of Toronto got private investment into what became Enwave. As a result the city was able to ensure the development of its deep lake water cooling project, with all the benefits that ensued.

Most municipalities see their utilities as a regular source of income, Floyd Laughren argues, rather than as entities requiring ongoing investment. The panel recommends that any funds from the disposal of excess utility assets, and much of the expected savings from increased efficiency, be reinvested in the system, rather than used as dividends.

Nevertheless, the panel is agnostic on privatization, Laughren said. For its part, the EDA believes private ownership should be limited to 49%, and that this should be permitted through changes to current transfer tax rules, and federal-provincial tax discussions so that existing payments-in-lieu going towards the reduction of the provincial stranded debt can continue. The panel also recommends getting rid of the transfer tax, which currently inhibits privatization.

The Panel believes that a majority of the directors on the Boards of restructured LDCs should be independent, and in particular without any particular ties to the original contributing shareholders (i.e., municipalities). The primary reason for maximizing their independence is to ensure that individuals in positions of governance are selected for their level of professional knowledge and expertise, and primarily responsible for providing high quality directorship and management.

On a greying workforce: The panel acknowledges a wave of retirements expected over the coming decade that threatens to cause a shortage of skilled labour in the province’s LDCs. Fort Frances Power at least disagrees: "Our current line crew is relatively young and will not be affected by further baby boomer retirements," said Ruppenstein.

On the 6-month timeline: The panel sees tight timelines as necessary to prevent the plan from starting to unravel. "The customers, and the Ontario economy, require that we get on with replenishing the system hardware now," says Elston. "It cannot wait long. Our competitive position, the viability of the economy, is something we cannot put at risk any longer. This is an exercise that must take place quickly."

On the likely political acceptability of their recommendations: In response to a question at the January 15 panel presentation, Floyd Laughren said he hasn’t heard anyone strongly oppose the panel’s ideas. The PCs support the concept of consolidation, while exercising caution about it making it compulsory. The NDP hasn’t released a specific policy position on LDC privatization, but it has indicated concern about elimination of the transfer tax becoming privatization by the back door.

The contrary point of view: Bigger is not necessarily better

It should be noted that a significant body of opinion takes a very different view from that of the Panel. There are those who argue, with some evidence, that some of Ontario’s smaller LDCs show a great deal of efficiency and innovation.

Jim Huntingdon of Niagara-on-the-Lake Hydro for example, recommends that policy analysts study carefully the level of distributors' cost and total bills by LDC size. He contends that such data reveal some interesting patterns and suggest that caution should be exercized in applying size-based assumptions across the board. Huntingdon notes that many of the smaller utilities welcome the opportunity to compete with, or be compared to, their neighboring larger LDCs on both rates and service levels. He says, “Kitchener Hydro for example is a ‘medium-sized’ LDC that has long been considered the model of efficiency for all LDCs and could blow away the large LDCs and certainly any proposed mega-LDC.”

He contends that once regulatory approval has been received, there is absolutely no problem securing debt capital at competitive rates for LDC investments. And the idea that smaller LDCs have trouble keeping up with technology is another misconception, he says: “Like Fort Frances, NOTL Hydro with a mere 8000 customers has developed a smart grid. Our historic Old Town relies on tourism. An outage during Shaw Festival plays would result in the refund of hundreds of thousands of dollars and area merchants turning away busloads of tourists. NOTL Hydro spent approximately $300,000 installing a self-healing system that restores power automatically in under 8 seconds. … The only old infrastructure left in our operating territory are remnants of the plant purchased from the last true mega utility – Ontario Hydro. Within 3-4 years, we will have completely rebuilt our system.”

Generators will be heartened by the fact that one of the central objectives of the Panel’s work was to ensure that LDCs in Ontario are better prepared to deal with generation connection requests in the future. Although generators in Ontario are in principle responsible for the cost of their own connections, there are exceptions for renewable generators, and in addition there will be some adaptation costs for utilities that aren’t fully prepared to deal with generation connection requests. No doubt, a sizable portion of the capital costs distributors are anticipating are likely to be generation-related, albeit often with multiple beneficiaries beyond the connecting generators. While the effort to locate capital to accommodate generation is generally positive news for generators, it is a very slow moving process and years may elapse before a given distributor will be ready to accept significantly more new generation connections than it does today. In addition, it is far from clear as to whether any new amalgamated distribution utilities, should they in fact be created, will be more or less likely to become active in generation development themselves, presumably through a similarly enlarged affiliate business of some kind.

There is little doubt that there are powerful economic pressures pushing in the direction of consolidation. The Panel seems to believe that the cause of efficiency will be best served by contiguous boundaries, which would mean having Hydro One’s distribution business completely broken up and integrated into that of other distribution utilities, a rather dramatic change for Hydro One Distribution. Unfortunately the Panel does not seem to have addressed directly the full implications of ending the reign of Hydro One Distribution in this way. Some stakeholders, Hydro One among them, will likely want to see a more complete set of options for dealing with Hydro One, and probably cost benefit analyses of each, before endorsing such a fundamental change.

Although some form of consolidation and possibly restructuring is likely in Ontario’s electrical distribution sector, it appears that significant development work still lies ahead before the model for any wide-ranging set of changes can be fully resolved.

The Panel's major recommendations

• Consolidate most of the present 80 LDCs through mergers (the recommendations apply to 73 utilities, with 7 excluded for various reasons), to a final number of 8 to 12 regional distributors. 2 distributors in Northern Ontario – one in northeast and one in northwest. The rest of Ontario to be served by 6-10 distributors, each with a minimum of 400,000 customers.

Ontario has almost twice as many LDCs as all of the remaining provinces combined.

At present there are 29 LDCs in Ontario that have fewer than 12,500 customers each. These ‘small’ LDCs account for over a third of all the utilities in Ontario, but less than 4% of the province’s electricity customers.

• The consolidated utilities should be contiguous and 'shoulder to shoulder,' that is, with no gaps between them. As Toronto Hydro is already large enough and contiguous it is expected to have no need to merge with any other. The others will benefit by removing duplication in equipment and service routes.

• Consolidation should be voluntary and occur within 2 years. A transition advisor should be appointed to monitor the progress of LDCs to agree to mergers, with LDCs reporting to the transition advisor on the status of such agreements within a six-month deadline (with a possible three-month extension). If it is evident from these reports that regional distributors cannot be formed through voluntary means, the government should introduce legislation to ensure consolidation is successfully completed.

• There should be no across-the-board sale of Hydro One Networks’ distribution assets, the government should direct Hydro One to lead discussions with LDCs to create regional distributors through mergers.

• Current owners of LDCs to receive equity in the new regional distributors in proportion to the value of assets contributed. The amalgamated LDCs should have at least 2/3 of their boards composed of independent members.

• To facilitate access to new capital, the province should work to remove the transfer tax as a barrier to private investment.

The Panel's further arguments and priorities

• Consumer focus. Utilities must be structured to provide high quality service, and the latest services to customers, as they become more demanding and engaged.

• Utilities must become as efficient as they can, to maintain Ontario's ability to compete with the rest of the world, to support the Ontario economy.

• Consolidated LDCs will achieve cost savings due to greater efficiencies in operations, maintenance and administration, to the benefit of customers. Savings will also accrue to the Ontario Energy Board from the reduced number of utilities.

• Consolidation will also allow the newly created regional utilities better and lower-cost access to investment capital. The Conference Board of Canada has estimated that Ontario's utilities will need to invest over $20 billion over the next 20 years, simply to maintain existing levels of service and meet customer growth. That does not include further investment to meet the demands of emerging technologies such as distributed generation, the smart grid, and electric vehicles.

• A contiguous, shoulder-to-shoulder pattern is needed to yield the most savings and provide maximum service.

For more information, see the Ministry’s page on the Distribution Sector Review Panel, at http://www.energy.gov.on.ca/en/ldc-panel/.

Key issues in resolving a model for LDC consolidation

Ontario’s distribution sector panel has raised a number of important questions about the principles and the critical features that should make up the model used by regulators and market participants to guide their work as the province seeks to reform its LDC sector. The discussion has become complicated because assumptions are quite divergent about what principles should be reflected in the target structure, and in the transition process – which could be a lengthy one.

Even if there is widespread agreement that the key objectives of LDC reform are achieving long term operating efficiencies (including those in capital financing) and improving the level of customer service, particularly in areas where it isn’t meeting certain standards today, universal agreement does not exist on the extent to which achieving other public policy objectives should be amongst the key objectives of reform.

The proposals for LDC reform themselves seem to be subject to redefinition and continual evolution. One way of helping to organize the discussion has been to analyze the options for reform in categories according to their key features. For example, in an attempt to identify the enduring features of the various proposals that may come under consideration, observers will often face common questions such as the following:

1. The role of Hydro One’s rural operations

Whether to leave the Hydro One franchise to operate in most rural areas of the province. This is a key decision area because it determines whether shoulder-to-shoulder regional distributors are geographically possible, as well as other questions.

2. Compulsory or voluntary approach

Whether to make the amalgamation of existing LDCs compulsory, or to rely on positive incentives to encourage consolidation.

3. Uniformity of service levels

Whether to allow “low service pockets” to continue in cases where the local ratepayers prefer the combination of lower service and lower rates (as opposed to uniformly moving to standard service levels with varying rate impacts).

4. Governance of the amalgamated regional utilities

Whether to require significant numbers of independent directors when previous municipal utilities are amalgamated into larger public entities. (Once privatized there will be relatively little control over governance structures.)

5. Should there be any regulation over the privatization process

Whether there need to be any limits on the speed and/or amounts of privatization after amalgamation and removal of the transfer tax.

6. The importance of uniformity in the application of the model

Under what conditions can there be exceptions to the model imposed? If some municipality doesn’t want to be part of a merger and is prepared to accept lower service levels and/or higher rates, should that be allowable?

Implicit in most of the above is the question of whether to try to preserve essentially unchanged the bond that currently exists between certain municipalities and their electric utilities.

What the LDC transfer tax means

Normal commercial companies effectively pay income taxes to both the provincial and the federal governments. Provincially and municipally owned LDC’s are treated differently however, and make payments in lieu of taxes (PILS), all of which flow to the province. This arrangement was designed primarily to help pay down the province's residual stranded debt in the electrical sector, left over from the restructuring implemented in 1998. Also, in order to retain these revenue streams to the province, the provincial government created the transfer tax, at a rate of 33%, that would apply to any sale of assets or business from a municipally-owned utility. Once private sector entities own more than 10% of the equity of an LDC, then the Transfer Tax is applicable. The current legislation provides, whenever such transactions take place, that the LDC is deemed to have exited the PILs system, and then the PILS payments would stop and conventional tax arrangements would begin. The perception is that without the transfer tax and PILs regime the province would suffer substantial losses to its stranded debt pay down program. This is in spite of the fact that (partially due to private sector ingenuity) the Province has never collected any material amount of transfer tax. However, according to the OEB, PILS payments in 2011 amounted to $133 million. So it is the annual PILs payments that are important to the provincial government.

As the panel notes, while the transfer tax does serve an important function of protecting the income stream to the province from distributors in lieu of taxes, it is also a major deterrent for private sector investment in the sector. John McNeil, President of BDR Energy and a member of the Board of Directors of Atlantic Power – currently an investor in the Ontario generation sector only – notes that terminating the tax would probably first need to involve some negotiation with the federal government so that the PILs cash flow stream, in whole or in part, somehow continues to flow to the province, perhaps through an arrangement whereby Ottawa would relinquish its share for a time, or accept a reduced share. As Ontario, like the other provinces, is more or less in constant negotiation with Ottawa over various issues such as the equalization framework, the subject could simply be added to the agenda.

It's also worth noting, McNeil points out, that the payments the LDC’s have been making over the years get credited against any transfer tax payable (in the event of a transaction). In fact, most Ontario distribution utilities over the 10 years the PILs regime has been in place probably have accumulated substantial credits (perhaps as much as 50%) against the transfer tax payable on closing of a transaction.

It is true, therefore, that the effect of the transfer tax diminishes over time and will eventually cease to be an issue. However, it would still take many years for the transfer tax credit to fully offset the transfer tax payable, whereas the LDC review panel report has stressed that there is a certain amount of urgency to its recommendations.