Smart Energy Instruments, a relatively new company in Toronto (incorporated in 2004, with its current name and focus dating from 2009) has designed what it calls a Smart Grid Sensor, a universal measurement and communications platform core for intelligent electronic devices (IEDs), something that company VP of Marketing Ken Tang says will enable utilities to squeeze more power onto the grid for a fraction of the cost of present-day technologies.

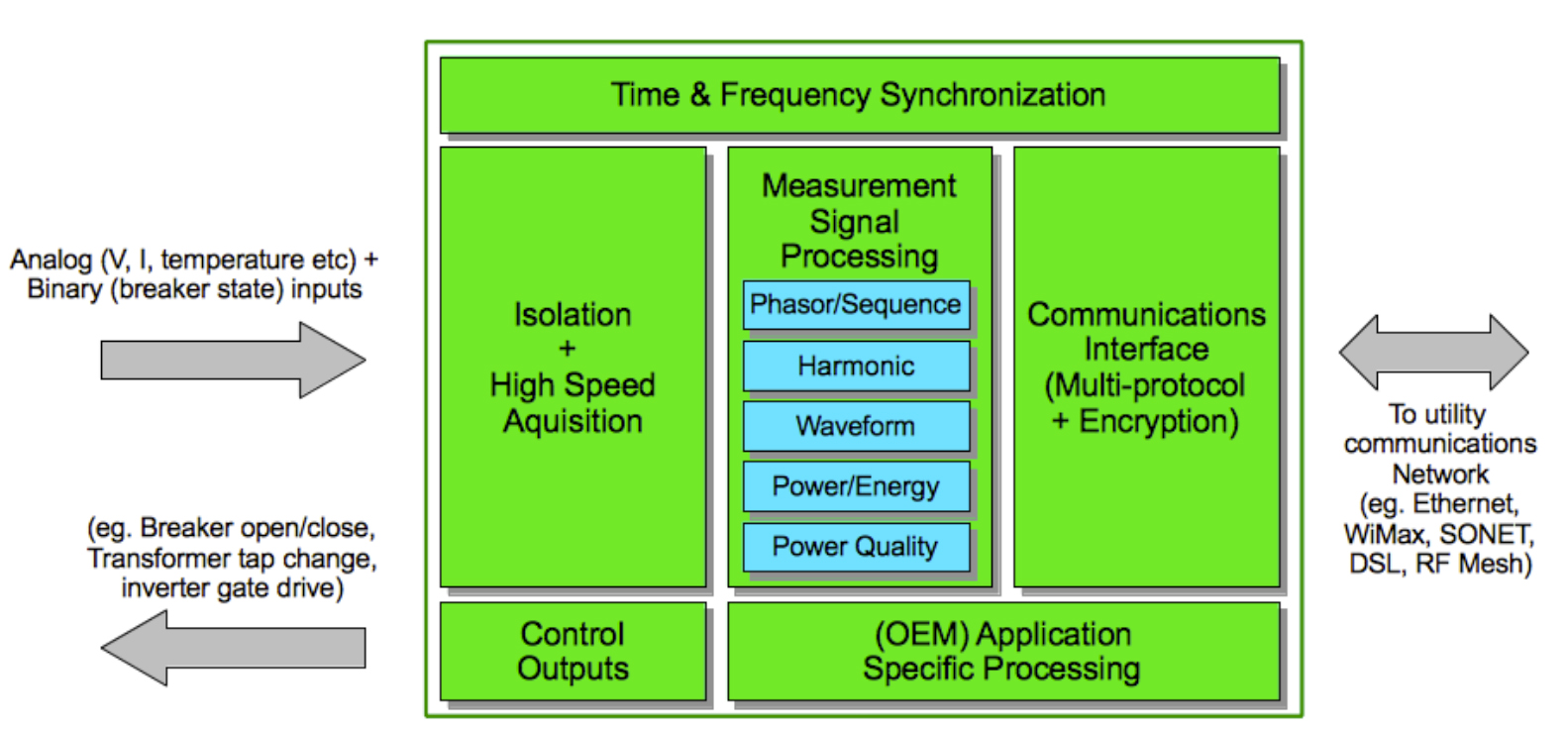

Mr. Tang explains that utilities currently use many different IEDs: protective relays, power quality monitors, dynamic line rating sensors, distribution automation controls, static excitation controls, and others – some twenty or so different categories of devices. All do some form of measurement, some form of communication and some form of control. All do it differently, not necessarily to the same standard, or with the same communication protocols, and the measurements are not synchronized from one device to the next. This becomes a problem when trying to coordinate power control measurements across a system. In order to accurately determine actual power flows on the grid, multiple measurements need to be taken across the system at the same time, Mr. Tang says: that is, simultaneously down to less than a millisecond error, across an entire grid. It sounds like quite a challenge, but he says his company’s design – which, once manufactured, will be a circuit board the size of a business card that incorporates a range of needed functions currently tacked onto devices built for other purposes, and will do that, within less than a microsecond error, using a signal from GPS satellites. In so doing, it will be used in systems that allow more power, more reliably, to travel through the same wires safely.

Such installations, however, can cost of thousands of dollars. In North America there are only some 800 phasor measurement units (PMUs) installed, Mr. Tang explains. He says his device, once perfected, can provide the same measurement functions as several different types of IEDs in a very cost-effective way.

Potential global markets are in the millions. There are some 70,000 substations to be found on the North American grid. Then consider all the transformers on poles and in underground vaults, each with its own sensor, or a feeder with several hundred loads, many with their own rooftop solar array, each one needing data collection and a way to control its contribution to the grid. Right now, partly given the limited types of monitoring & control that the distribution utility can apply, utilities impose what Mr. Tang describes as a very conservative and somewhat artificial limit on how many distributed energy sources can be connected to a feeder. Ken Tang says his technology is one key to unlocking that potential, by creating an intermediary to amalgamate and control inputs from a single feeder, and talk to the local substation.

The design is currently undergoing a demonstration trial at Brookhaven National Laboratories in the United States. The company has proposed such a virtual power plant project with the University of Toronto.