After generations of being disregarded and worse, First Nations in Ontario are turning in increasing numbers and with increasing success to taking control over the development of energy resources on their own lands and traditional territories.

Energy project development, now generating not only construction jobs but a steady stream of revenue and, equally valuable, a sense of accomplishment and pride of ownership, bids fair to brighten a future too often clouded by unemployment and despair. Now, “Almost every month in Canada a press release is posted announcing a partnership among First Nations and developers from Canada’s resource sectors,” observes Cherie Brant, a lawyer with Willms & Shier Environmental Lawyers LLP in Toronto.

As the sample of projects listed here shows, First Nation communities, empowered by a new recognition of their rights over treaty and traditional lands, are one by one taking charge in a new and confident way of the development potential on their lands. This brief summary attempts to gather some of the commonalities, as well as the variations in that experience.

“We have clients that did not obtain a FIT contract, but you can bet they are still interested to find ways to become a part of the projects that are taking place in their traditional territories,” Brant continues. “I would not be surprised if we start to see First Nation communities looking into purchasing projects post commercial operation as long term investments,” she says.

Important among the recently-created mechanisms to facilitate First Nations’ entry into ownership positions in power projects are initiatives by the Ontario Power Authority and the Ontario Financing Authority:

• The Aboriginal Renewable Energy Fund (AREF), created by the OPA, is available to assist with some of the initial project development costs associated with First Nation and Métis community renewable energy projects. AREF funding is available for three phases of project development:

» Pre-Feasibility Phase: 80 percent of actual costs.

» Design and Development Phase: 60 percent of actual costs.

» Regulatory Approvals Phase: 40 percent of actual costs.

See also “Ontario’s Aboriginal Energy Partnerships Program / Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program” article from IPPSO FACTO, August 2011.

• The OPA also has a Aboriginal Community Energy Plans (ACEP) program to assist communities to identify and act upon their local conservation and renewable energy development opportunities. The ACEP Program will provide funding in three areas:

» Education, vision and creating a community profile

» Carrying out a community baseline study

» Developing a community energy plan.

The above are part of the OPA’s Aboriginal Energy Partnerships Program. The Aboriginal Renewable Energy Network is a web-based resource providing information on the program, at www.aboriginalenergy.ca.

• The Ontario Financing Authority (OFA), which manages the province’s debt and borrowing program, operates an Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program (ALGP), with a budget of $250 million, that can provide a guarantee for a loan to purchase up to 75 per cent of an Aboriginal corporation’s equity in an eligible project.

Paul Manning of Manning Environmental Law, who represents the Assembly of First Nations and Chiefs of Ontario on various energy issues, observes that “(Many) First Nations want to participate in Ontario’s energy industry given a fair opportunity,” and several have demonstrated the ability to attract private capital. He is concerned however that, “Although the opportunities provided by government to date, such as the Price Adder and AREF are welcome, they are still insufficiently extensive and flexible.” Environmental impact will remain a key a key factor that First Nations will balance against the economic advantages of a project.

Several such projects under development are profiled in the reports below.

Mnidoo Mnising Power, United Chiefs and Council of Mnidoo Mnising (Manitoulin Island)

The project, known as McLean’s Mountain, is a windfarm developed by a partnership of Mnidoo Mnising Power and Northland Power. Northland got involved in this project around 2004, following up on a Request for Proposals by the city of Sudbury, seeking 50 MW of capacity. Northland took over a project initiated by a small private developer on Manitoulin Island, initially prepared for RES 1, brought it through several rounds of permitting, and ultimately reshaped it for the Feed-in Tariff program.

At the same time, the United Chiefs and Council of Manitoulin (as it was at the time) had been considering the creation of a jointly-owned power company, as part of their economic development strategy. After detailed negotiations, the two formed a partnership in 2010, allowing the project to take advantage of the FIT’s aboriginal price adder and the Ontario Finance Authority’s Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program. The UCCM was renamed the United Chiefs and Council of Mnidoo Mnising (UCCMM) in 2010.

“This partnership is historical,” says Art Jacko, Lands and Resources Manager for UCCMM. “It marks the first ever First Nations/Private Sector partnership in renewable energy and sets a new bar (50-50 shared ownership) for Aboriginal-Private Sector partnerships in the future. The shared ownership between Mnidoo Mnising Power and Northland Power is an important model of how First Nations can work closely with the private sector and government on something that both benefits their people and supports the Province of Ontario’s leadership in renewable energy.”

“This is the way these projects ought to be done,” adds Northland President John Brace. “If you’re open to these things they can be very rewarding.” Art Jacko observes that, like many other First Nations with potential projects, they had been inundated by requests from a wide range of proponents – the difference between that and working with Northland Power is “like night and day,” he said.

The 50/50 partnership with Northland Power starts with the McLean’s Mountain Wind Farm Project but includes options for future renewable energy projects on the UCCMM First Nations’ traditional territory, and down the road may include solar, hydro, gas or electrical infrastructure projects.

Project summary

Location: McLean’s Mountain, Manitoulin Island

Size: 60 MW

Company name: Mnidoo Mnising Power / MacLean’s Mountain Windfarm

Project partner: Northland Power

Project structure: Mnidoo Mnising Power was created and is jointly owned by United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising, representing six First Nations on Manitoulin Island (M’Chigeeng First Nation; Sheguiandah First Nation; Sheshegwaning First Nation; Aundeck-Omni-Kaning First Nation; Whitefish River First Nation; and Zhiibaahaasing First Nation). Ownership and revenue stream are shared 50-50 between Mnidoo Mnising and Northland Power. Debt / equity ratio is expected to be around 70 / 30.

Financing: Northland Power will likely provide some of the equity financing, depending on developments with its other projects. UCCMM will apply for the Aboriginal Loan Guarantee from the OFA.

Government-sourced funding: AREF, to date.

Timeline:

• Renewable Energy Approval (REA) is almost complete, approval expected by the end of October.

• Financing is underway, completion expected early in 2012.

• Construction to begin in spring 2012

• COD in fall 2012.

Suppliers and contractors: GE will supply 24 2.5 MW turbines.

Connecting line: Not required.

Mother Earth Renewable Energy (MERE) Wind Farm, M’Chigeeng First Nation

“We consider our community one of the most advanced in Ontario when it comes to Renewable Energy at the community development level,” says Economic Development Manager Grant Taibossigai of M’Chigeeng First Nation, on Manitoulin Island. “Our goal was to use our resources and funds from government sources and internal resources in a way that benefits the entire community as a whole. We had community meetings every year for six years on this project and the main message from our community membership was that M’Chigeeng First Nation should own the project entirely.”

That meant the project should be entirely on M’Chigeeng First Nation lands. As a result, the project evolved from an original dream of 10 MW of generation and located across a land portfolio of Reserve and Non-Reserve properties (although land owned by Band members), to a smaller concept of 4 MW of generation located exclusively on reserve. The sense from the community was that the larger project would result in too much economic benefit flowing to a small group of people (land owners) and outside investors, and therefore the community asked for a smaller project to create more proportionate benefits.

In an echo of experiences emerging from other communities, the project concept emerged from community discussion – “and therefore there is a lot of community buy-in and now we have 100% ownership,” says Taibossigai.

The Band conducted a combined federal and provincial environmental assessment and then received a provincial waiver of EA under the new FIT regulations. Notwithstanding the provincial waiver, the Band chose to respect the set-back distances set out in the provincial regulations. “We wanted our project to meet all current EA requirements and standards, so we could satisfy anyone in the community or government who might ask,” Taibossigai said. Locals familiar with harvesting of traditional medicines assisted with the EA field work.

Mr. Taibossigai notes that the M’Chigeeng First Nation had input to the development of the existing government support programs designed for First Nations. Six years ago the M’Chigeeng First Nation wanted the project to be a contender in the Ontario’s RFP procurement process but they did not have the necessary capital and technical resources at hand. Then when Ontario introduced the RESOP program (the original Ontario Standard Offer Program), the project met with frustration in being shut out from grid access, a common obstacle faced by First Nations. “We urged the Ontario government to create programs specific to our needs,” Taibossigai says. “Finally, with the assistance of the Ontario Sustainable Energy Association and the First Nations Energy Alliance (FNEA), M’Chigeeng First Nation along with other Ontario First Nations convinced the Premier of Ontario and the Ministry of Energy to support the development of AREF, a fund that assists aboriginal proponents of generation projects, as well as the Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program.”

Even then, he says, “We had a prolonged and challenging process to get the project’s loan approved for the guarantee. The technical barriers associated with project corporate structure, loan security and real property matters were daunting. Federal processes associated with permits for non-aboriginal entities on Band property did not exist particularly for the project’s circumstances, which meant the project was creating a precedent within Indian and Northern Affairs Canada’s (INAC) world of procedures. There was a lack of alignment between provincial loan security requirements to support the loan guarantee and the INAC land permitting processes in existence. That resulted in extra delays and legal expenses. “We never expected it would take 15 months to get the loan ready for disbursement, and it’s hard to herd all the cats in the loan approval chain even when there are immoveable project deadlines to be met.”

Project summary

Location: Manitoulin Island

Size: 4 MW, two wind turbines

Project cost: $12.5 million

Company name: MERE General Partner Inc.

Project partner: None. The MERE board engaged 3G Energy in Ottawa for project management services, and Willms & Shier for legal services.

Project structure: Entirely Band-owned

Financing: Initial phases cost about $800,000, with about 60% from provincial and federal funding. $4 million will be in equity, in the form of internal loans, repayable to the Band.

Government-sourced funding: FEDNOR provided about $400,000 for the capital phase, and INAC $500,000. OFINA has provided an $8.5 million loan guarantee.

Timeline:

• Project initiated in 2004

• FIT contract received

• Notice to Proceed received

• Access road completed, construction has commenced, tower foundations poured

• Delivery of turbines scheduled for October 3, erection in November.

• COD in January or February

Suppliers and contractors:

Connecting line: only about 1 km long, almost all on Band land except for a short stretch on private land.

Bkejwanong (Walpole Island) First Nation

The story of Walpole Island’s renewables projects is shorter than most: The main undertaking, a 10MW wind farm project, is essentially on hold until the local connection capacity gets upgraded, which is currently scheduled for 2017. However, there is capacity to absorb a megawatt or two, and the band has set up and connected one 10 kW rooftop photovoltaic installation, with six more coming, including 50 kW on the roof of the sports centre. Projects under the OPA’s MicroFIT program are a “slam dunk,” says energy consultation consultant Ed Gilbert.

The windfarm could have been made as large as 60 MW, but the band council decided to go with 10 MW, the smallest for which the economics were favourable. The project will be located entirely on farmed land belonging to Walpole First Nation, the location chosen for proximity to the substation just across the river in Wallaceburg. The only EA potential concern is a nearby bird migration route. Walpole Island is the duck-hunting capital of the world says Gilbert, but with the marsh a mile away there’s nothing to attract ducks in the vicinity of the project.

Project summary

Location: Walpole Island, Lac St. Clair

Size: 10 MW, wind

Company name: WIFN Utility Corp.

Project partner: None at present.

Financing: All spending so far has been from Band money.

Government-sourced funding: None yet

Timeline:

• Environmental assessment is partly done.

• The windfarm is waiting on connection availability; lines are not to be upgraded until 2017.

• First rooftop PV was connected last October under MicroFIT. Six more are in process, as well as two 1 MW ground-mount PV fields.

Suppliers and contractors: none yet

Connecting line: directly across the river to connection point in Wallaceburg

High Falls and Manitou Falls, Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation

The experience of the Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation shows what twenty years of work in the power sector can do.

Having participated in the Twin Falls hydro facility with developer Rapid-Eau Technologies, a facility commissioned in 2001 and ownership of which it subsequently took over entirely, the band is now prepared to undertake two more hydro projects on the same river entirely on its own. High Falls and Manitou Falls, 3.2 and 2.8 MW respectively, will represent a total investment of $35 million or more, for projects that will be owned and developed entirely by the Pic River band. So far, the band has spent close to a million dollars of its own money, reinvested from other hydro revenue, in preparatory work. It also owns the Umbata Falls facility on the White River. All the projects are or will be run-of-river.

“Who’d have thought that?” says Energy Projects Director Byron Leclair with satisfaction, speaking of a Band-run $35 million project. “But this is part of the path we’ve been on for twenty years.”

In addition to internal financing, the preparatory work has been financially assisted by AREF, to date the only program the band has sought funding from.

Although others have expressed frustration with the various provincial and federal funding programs, Leclair says AREF is “an appropriate support mechanism, aimed at First Nation participation in these projects.” He notes that, “the template is fairly inflexible, but that said, it’s fairly clear as to what they expect to be delivered. So long as you understand what the program wants, and can work within those guidelines, it shouldn’t be a problem. Ontario has led the way in transforming aboriginal involvement in energy, and the OPA has played an integral role in that.

It seems to be a common experience, however, that some flexibility is needed in getting underway. In Pic River’s case, “Our ability to be flexible stems from our access to our own equity,” notes Leclair. “Our projects aren’t beholden to the program, and that really changes the experience. I don’t think the program is particularly onerous. But we also have twenty years of experience in this industry. These are not surprises to us.”

In fact, Pic River is also developing a partnership with five other First Nations to build, own and operate a transmission line, which will be able to carry power from several other power developments underway to the grid. More information on this undertaking is not available at present.

Project summary

Location: High Falls and Manitou Falls, two sites on the Pic River

Size: 3.2 and 2.8 MW respectively

Project cost: $35 million or more.

Project partner: No general partner at present, no current plans for one.

Project structure: Wholly owned by the Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation

Financing: Not yet begun

Government-sourced funding: AREF to date.

Timeline:

• Site study field work begun March 2010

• EAs for the two facilities awaits completion of fisheries data, expected in 2012. Water levels in 2010 were at a record low, so that another year’s worth of data are wanted for a better picture of normal flow.

• Awaiting successful Economic Connection Test

Suppliers and contractors: Hatch is working on the EA. Chant Construction is doing design and engineering. In discussion with Canadian Hydro Components for equipment.

Connecting line: existing transmission facilities at Twin Falls will be extended.

Gitchi Animki (Big Thunder) Hydroelectric Project, Pic Mobert First Nation

“Power procurement policy has just gotten better and better,” says project liaison Norm Jaehrling. “In 2000 ours was a marginal project, but with the RESOP, then the FIT, the aboriginal adders, and so on, now it’s viable. There’s been a substantive commitment to First Nation equity participation. These are real game-changers. Energy is one area where development can really make a difference to the community. We’re not talking about impact agreements with mining companies – which have their role – but we’re at the table, not as an interest to be managed, but as equity owners and active participants.”

Unlike the experience others have reported, Jaehrling has no issues with the funding programs. “We found that they would adjust to our stage of development. Some have said AREF is more for early stages, but we were well into our development, and they were able to work with us to capture costs that we had yet to incur. We’ve had a very good experience,” he said.

Consultation has also been very successful, Jaehrling says. “We’ve done more public consultation, we believe, than any other hydro project ever has in Ontario. We started speaking with stakeholders before the formal EA began – cottagers, recreational users, tourists, trappers, neighbouring First Nations. The extent and depth of our consultation is reflected in the fact that when we went to the final public consultation, where the opportunity exists for anyone to request a bump-up to full EA, nobody did. That’s very unusual for a hydro project.”

Project summary

Location: two sites on the White River, Gitchi Animki Niizh and Gitchi Animki Bezhig

Size: 10 MW and 8.9 MW respectively

Project cost: about $135 million

Company name: Pic Mobert Hydro Power Joint Venture / Gitchi Animki Energy Corporation

Project partner: Regional Power Inc.

Project structure: Equal partnership, in ownership and revenue.

Financing: Typical for this type of project. Negotiations underway.

Government-sourced funding: AREF approved and OFINA guarantee is in process, but will await close of project financing.

Timeline:

• Development rights to the site first awarded in 1993. Pic Mobert FN began pursuing the project in 2000, development begun in 2004.

• EA completed

• FIT contract awarded under the first round, March 2010

• Final design underway, tender for balance of plant to be released this fall.

• Construction to begin first quarter 2012

Suppliers and contractors: Discussions underway. Regional Power is project manager.

Connecting line: 20 km. Connection capacity is committed.

Lower Mattagami complex redevelopment, Moose Cree First Nation (MCFN) / Ontario Power Generation

The Moose Cree story is perhaps the embodiment par excellence of the First Nation experience with resource development summarized here, beginning in 1992 with the old-style approach that, as Chief Norm Hardisty puts it, “destroyed our lands, displaced our people, did a lot of things without our consent. … In 1992 we weren’t even allowed to use lawyers. Governments weren’t interested in serious discussion.”

The intervening nearly two decades have made quite a difference. The landmark legal cases over the intervening years have helped a lot, Chief Hardisty notes, and now of course the duty to consult is clearly set out in exacting detail. Even so, there’s a difference between pro forma compliance and full engagement as a business partner. OPG has offered a formal apology for past conduct, under Ontario Hydro as it was at the time, that convinced the band council and community (after some twenty separate consultations with band members on and off reserve) that OPG is sincere.

“Now, it’s stated right at the beginning of any discussion with developers: you have to respect our treaty rights. This time around, OPG accepted the principle right away,” says Hardisty. “We’ve talked with them quite a bit over the last two or three years, gave them a good lesson on how our culture operates, and every time [we sat down at the table] it got better.”

Carlo Crozzoli, Vice President of Hydro Development at Ontario Power Generation, concurs.

“We’ve taken a proactive approach to dealing with some of these historic grievances,” he said in a phone interview October 13. “As it’s well recognized, in the past a lot of the hydro resource in the province has been developed without due consideration to the aboriginal people who live there, and they had impacts on the traditional territory and way of life. This is a new paradigm for doing hydro development in the north, for sure.”

As examples of the new kind of regime, a the Ontario Ministry of the Environment formed the Mattagami Extension Coordinating Council in May 2010, with equal representation from the First Nation and Ontario government, to oversee and regulate the project to deal with environmental impacts, and with the ability to order additional restoration projects. The MCFN will have the majority of members on this council. An Environmental Coordinator has been hired, at OPG’s expense but who reports to MCFN. At the federal level, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) must also ask Aboriginal Peoples and the public for their opinion and advice. DFO is to prepare a First Nations Consultation Plan and a Public Consultation Plan.

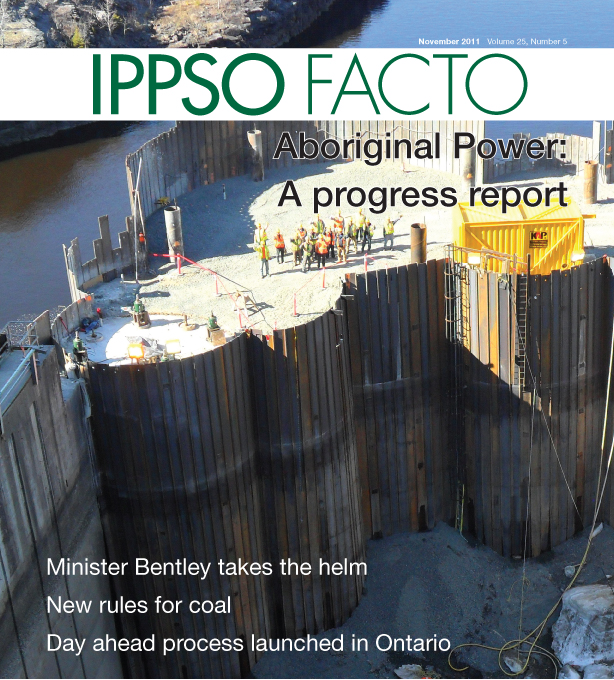

Crozzoli also points to a substantial local benefit created by employment on the four sites. “ Right now at the end of September there are over 250 aboriginal employees working on the projects, almost a third of the total workforce,” he notes. “That’s a huge success story from our perspective. There’s a very extensive training and apprenticeship program we put people through. The EA that governs the project required a minimum of 200 person-years of First Nation employment – we’ll exceed that within two years of the project’s beginning, and it’s a five-year project. These are core skills – we’re building capacity for a large pool of people in the north, who can use the skills for other projects. It’s a great opportunity for OPG to partner, and it smoothes the project development process.”

Moose Cree First Nation has created a corporation, Amisk-kodim, that is overseeing $200 million worth of construction contacts, with all the economic benefit that entails for the community.

“Back then there was no such thing as ownership by First Nations,” says Hardisty. “Now we’re moving away from the shackles of dependency. There’s a lot of First Nations going through drug and alcohol abuse, suicides – if we want a healthy community we have to have a healthy economy.”

Project summary

Location: Four generating stations (Little Long, Smoky Falls, Harmon and Kipling) on the Mattagami River, about 70 kilometers northeast of Kapuskasing

Size: The redevelopment will add 438 MW of new capacity to the existing four stations, almost doubling the total to 924 MW.

Project cost: $2.6 billion

Company name: MCFN / OPG Partnership

Project partner: OPG

Project structure: Moose Cree First Nation is targeting 25% ownership of the capacity additions to the four sites, contingent on financing being completed by the 2014-2015 in-service date; financing is expected to be complete before that.

Financing: Accessed OFINA loan guarantee. May access AREF for future projects.

Timeline:

• Initially proposed by Ontario Hydro in 1992, rejected by the Band council in 1994.

• Negotiations resumed in 2005 at the initiative of Moose Cree First Nation, with another round in 2007, and ratified by the Moose Cree community in May 2009.

• Construction begun in 2010, completion expected in 2015.

Suppliers and contractors: Under the Amisk-oo-skow Agreement, Moose Cree businesses will have priority to supply the project, as long as they can do so at a fair price. The MCFN has set up its own company, Amisk-kodim Corp, to facilitate and implement business contracting opportunities. Amisk-kodim Corp will be 100% owned by Moose Cree citizens.

Pape Salter Teillet, a law firm based in Toronto and Vancouver, is legal counsel.

Connecting line: The four facilities are of course directly on the existing transmission line.

Pukwis Community Wind Park, Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation / Windfall Ecology Centre

The project emerged out of discussions with Windfall Ecology Centre, an environmental non-profit organization and social enterprise based in Aurora, Ontario, which has been working with Georgina Island First Nation for some years on energy efficiency. In fact the partners developed what Windfall Centre Executive Director Brent Kopperson describes as the first community-wide home energy efficiency retrofit in Canada, completed in 2006.

Project summary

Location: Georgina Island, Lake Simcoe

Size: 20 MW wind

Project cost: not available

Company name: Pukwis Energy Coop

Project partner: Windfall Ecology Centre

Project structure: The wind park will be 51% owned by Georgina Island FN and 49% by the Pukwis Energy Coop. That in turn will be 51% owned through shares, to be offered to Georgina Island residents, and 49% by Windfall Ecology Centre.

Financing: Information not available

Government-sourced funding: AREF funding received (amount not disclosed), OFINA loan guarantee being sought.

Timeline:

• Contract received in the initial round of offers under the FIT program.

• Contractors and suppliers are under discussion.

• Construction to commence in spring of 2012, COD in fall of 2012.

Suppliers and contractors: negotiations under way. Willms & Shier Environmental Lawyers LLP are legal counsel.

Connecting line: 2km, connection capacity committed.

Sagatay Transmission L.P., Mishkeegogamang First Nation and the Ojibway Nation of Saugeen / Morgan Geare

This project is different from the rest, in being, first, a privately-owned transmission line, and second, one planned not to bring power to the grid from new generation projects, but to supply power from the grid to mining companies and remote First Nation communities in northwestern Ontario. However, it belongs in this list as an energy project with full direction and equity participation by First Nations.

Toronto-based private equity and consulting firm Morgan Geare lays claim to extensive experience in the electricity sector, especially in Ontario’s northwest, but this is its first foray into transmission development. The company partnered with Mishkeegogamang First Nation and the Ojibway Nation of Saugeen on the project as they are the two First Nations whose traditional territory is most impacted. Discussions have been going on for some time, said Project Manager Tri Luu, but the Long-Term Energy Plan has given it the needed boost to begin development. The project is going well, thanks to the company’s commitment to consultation – “Engage all stakeholders early and often,” he says. Traditional knowledge of the area has been sought out in design, to understand and respect traditional land uses.

“We have always said that we must be proactive in seizing a leadership role in economic development opportunities that may benefit and affect our community. Our treaty rights and our traditional way of life must be protected. This project will cut right through the heart of our traditional territory, and so we are extremely pleased to be in a position to work to minimize its impact, while optimizing the benefits for our people. This is exactly where we need to be,” said Chief Edward Machimity of Saugeen First Nation.

“It has always been the spirit and intent of our treaty to share our lands for the benefit of all peoples as long as the sun shines. For far too long, First Nation interests have been secondary to that of industry. The needs of industry must be balanced with First Nation interests. We will ensure that occurs,” said Chief Connie Grey-McKay of Mishkeegogamang.

Project summary

Location: The proposed project is to follow the existing right of way along Highway 599 from Ignace north to Pickle Lake, in northwestern Ontario. The project has been given high priority under the Long-Term Energy Plan.

Size: 230 kV, 300 km long

Project cost: $250 million

Company name: Sagatay Transmission L.P.

Project partner: Morgan Geare

Project structure: Shared ownership and revenue, comparable to the 50/50 model described here in other projects.

Government-sourced funding: Approaching AREF and OFINA

Timeline:

• Commencement of construction expected in 2013. Developments in the IPSP may affect the timeline.

Brundtland statement on traditional knowledge

“Their very survival (of indigenous and tribal peoples) has depended upon their ecological awareness and adaptation … These communities are the repositories of vast accumulations of traditional knowledge and experience that links humanity with its ancient origins. Their disappearance is a loss for the larger society, which could learn a great deal from their traditional skills in sustainably managing very complex ecological systems. It is a terrible irony that as formal development reaches more deeply into rain forests, deserts, and other isolated environments, it tends to destroy the only cultures that have proved able to thrive in these environments.”

— “Our Common Future,” World Commission on Environment and Development, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1977, pp 114-115.