Describing Western Canada’s electricity grid as poorly integrated, the Canada West Foundation released Power Without Borders in November, calling for its integration.

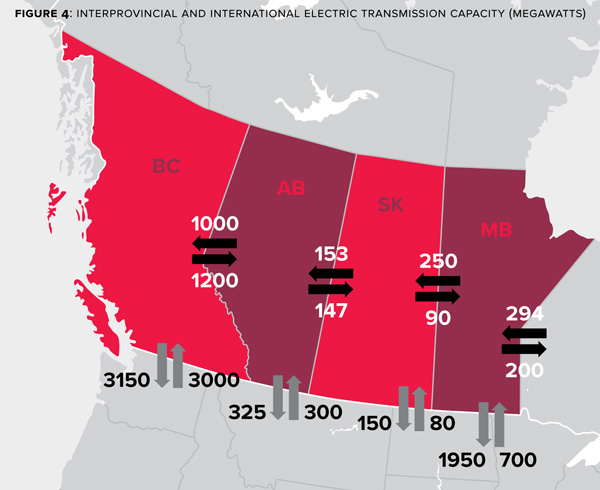

“The way the provinces’ markets are structured, regulated and planned makes it difficult to trade electricity across provincial borders – even if there was adequate infrastructure in place to do so, which there is not,” the group says, a status quo that political inertia and economics have entrenched.

A more integrated grid increases the value proposition of clean electricity, it continues, by enabling areas with substantial and low-cost clean electricity resources to access distant demand centres that would otherwise have to rely on more expensive electricity options.

It would also

• Make it easier to manage large amounts of variable renewables like wind and solar on the grid by reducing the overall variability of these resources over the entire system. When the wind is not blowing in one place, it is probably blowing somewhere else.

• Increase the diversity of electricity resources, bringing together complementary resources that work better together. In the West, hydroelectricity and wind generation work synergistically.

• Share the infrastructure needed to meet peak demand and maintain reliability. Sharing these resources reduces waste and lowers overall costs for consumers.

Recommendations include:

• Participate in energy imbalance markets.

• Strengthen regional transmission planning.

• Build new transmission infrastructure.

• Put electricity on the interprovincial trade agenda.

Provinces on either side of the Alberta-Saskatchewan border are part of different synchronous grids. British Columbia and Alberta are part of the Western Interconnect, while Saskatchewan and Manitoba are part of the Eastern Interconnect. Their grids do not operate synchronously, meaning the generators connected to each system do not operate at the same frequency and speed – a prerequisite for a stable and reliable alternating-current grid. For this reason, the two grids cannot directly connect to each other through alternating-current (AC) transmission lines. Instead, they must be connected by direct current (DC) transmission links, which require additional infrastructure and costs to convert electricity from AC to DC and back to AC again. However, due to lower per-kilometre costs and lower line losses, high-voltage DC transmission lines can be economical over long distances.

Provinces on either side of the Alberta-Saskatchewan border are part of different synchronous grids. British Columbia and Alberta are part of the Western Interconnect, while Saskatchewan and Manitoba are part of the Eastern Interconnect. Their grids do not operate synchronously, meaning the generators connected to each system do not operate at the same frequency and speed – a prerequisite for a stable and reliable alternating-current grid. For this reason, the two grids cannot directly connect to each other through alternating-current (AC) transmission lines. Instead, they must be connected by direct current (DC) transmission links, which require additional infrastructure and costs to convert electricity from AC to DC and back to AC again. However, due to lower per-kilometre costs and lower line losses, high-voltage DC transmission lines can be economical over long distances.

See also “NREL, 18 State governors advocate uniting power grids,” also in this issue.