Toronto: In a report released April 6, Canada's Ecofiscal Commission called on Canada's provinces to make “wise choices” in how they recycle the revenue from carbon pricing. Provinces are faced with many options and trade-offs; the report argues that, done right, revenue recycling can make the economy and environment “work better for all Canadians.”

"Carbon pricing is happening in Canada and around the world because it is the most cost-effective way to address climate change," said Commission Chair Chris Ragan, an associate professor of economics at McGill University and member of the Federal Government's new Advisory Council on Economic Growth. "The revenue presents both opportunities and choices – some are better for the environment, others for the economy."

"The reality is that each province has unique challenges – from helping industry to investing in technology to cutting taxes," Ragan continued. "This report shows that, by recycling revenue wisely, governments can ensure our industries stay competitive and that carbon pricing is fair to households."

The primary objective of carbon pricing is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the Commission points out, but the price is only half the story. Carbon pricing can generate substantial revenue for provincial governments. As the price ramps up over time, provincial governments need to choose what to do with the revenue. How this revenue is recycled back into the economy can affect both economic and environmental objectives.

The new report, Choose Wisely: Options and Trade-offs in Recycling Carbon Pricing Revenues, focuses on the costs and benefits of six revenue recycling options:

1. Transferring revenue to households

2. Reducing existing tax rates

3. Investing in emissions-reducing innovation and technology

4. Investing in critical public infrastructure

5. Reducing government debt

6. Providing transitional support to industry.

Using findings based on detailed economic computer models, the Commission argues that each province will have to find its own way among a number of competing options, based on that province’s individual economic mix. Each of the above approaches has its particular value, but also its weaknesses, and the weight of most of them will vary from province to province.

To a degree, the only exception would be the first, returning the revenue gained directly to the province’s residents, as in BC. It has the merit of being the easiest to apply, and an unambiguous, economically progressive result – the lowest income households benefit the most. The Commission’s analysis suggests that returning their proportion of revenue to at least the lowest income quintile, or possibly the bottom 40%, would be a desirable component in any province’s strategy, whatever else it does with the remainder.

To a degree, the only exception would be the first, returning the revenue gained directly to the province’s residents, as in BC. It has the merit of being the easiest to apply, and an unambiguous, economically progressive result – the lowest income households benefit the most. The Commission’s analysis suggests that returning their proportion of revenue to at least the lowest income quintile, or possibly the bottom 40%, would be a desirable component in any province’s strategy, whatever else it does with the remainder.

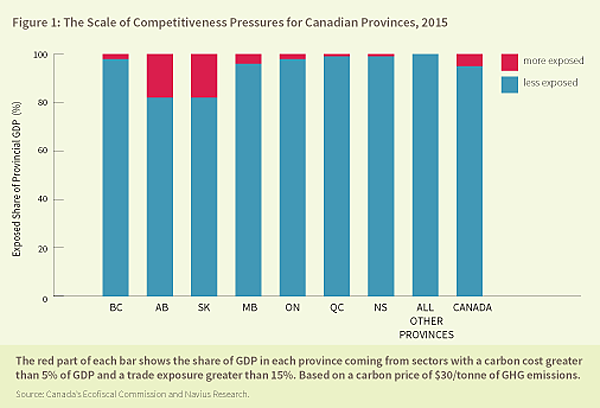

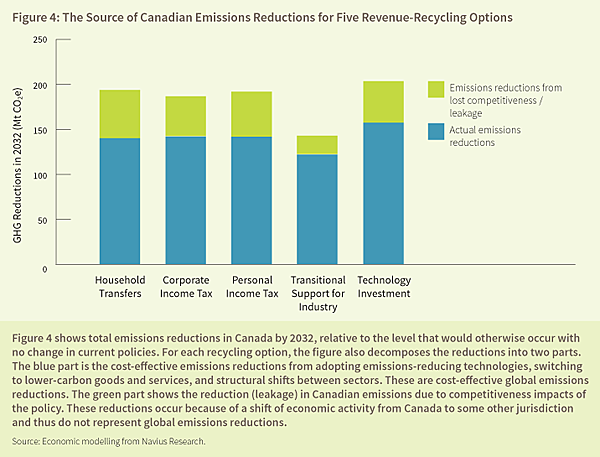

From there, it becomes more complicated. Thanks to their mix of industries, for example, Alberta and Saskatchewan are the most exposed to competition from economies without a carbon price (figure 1, above), so that they would probably want to include a measure of option 6, transitional support for those industries. On the other hand, figure 4 at right shows that this strategy would also result in a lesser reduction of absolute GHG emissions (the blue part of the bar) as those industries continue to generate GHGs during the intended technological transition.

From there, it becomes more complicated. Thanks to their mix of industries, for example, Alberta and Saskatchewan are the most exposed to competition from economies without a carbon price (figure 1, above), so that they would probably want to include a measure of option 6, transitional support for those industries. On the other hand, figure 4 at right shows that this strategy would also result in a lesser reduction of absolute GHG emissions (the blue part of the bar) as those industries continue to generate GHGs during the intended technological transition.

Figure 7 also shows that all the options, except for that one (output-based allocation), are projected to produce about the same reductions.

Figure 7 also shows that all the options, except for that one (output-based allocation), are projected to produce about the same reductions.

In an attempt to compare all the strategies for the five provinces with the largest economies, the Commission proposes the following table:

Summary of possible priorities for provincial revenue recycling, by province

|

| British Columbia | Alberta | Ontario | Quebec | Nova Scotia |

| Household Transfers | Moderate Priority | Higher Priority | Lower Priority | Lower Priority | Higher Priority |

| Personal & Corporate Income tax cuts | Lower Priority | Lower Priority | Lower Priority | Higher Priority | Higher Priority |

| Investments In low-carbon technologies | Higher Priority | Higher Priority | Higher Priority | Moderate Priority | Moderate Priority |

| Investments in Infrastructure | Moderate Priority | Moderate Priority | Moderate Priority | Higher Priority | Lower Priority |

| Reducing Public debt | Lower Priority | Lower Priority | Moderate Priority | Moderate Priority | Lower Priority |

| Transitional Support for Industry | Moderate Priority | Higher Priority | Lower Priority | Lower Priority | Moderate priority |

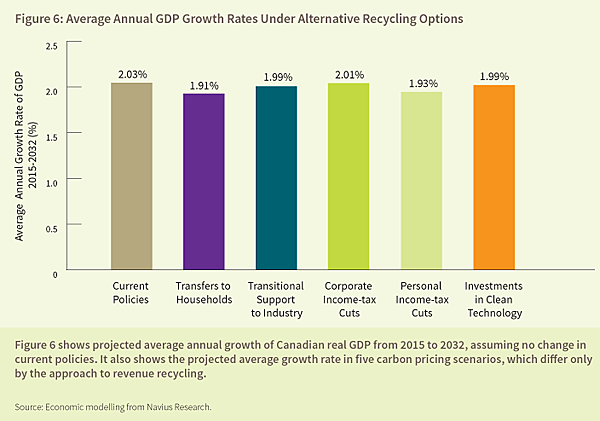

A final note: the Commission’s analysis shows that the actual effect on Canada’s real growth in GDP is remarkably constant across all the options, with the effect varying between them by only a minuscule amount (figure 6). Whatever the country as a whole does, growth will be about 2%, plus or minus an amount too small to measure (the two digits to the right of the decimal point are only there for illustrative purposes). That has to provide some measure of assurance.

A final note: the Commission’s analysis shows that the actual effect on Canada’s real growth in GDP is remarkably constant across all the options, with the effect varying between them by only a minuscule amount (figure 6). Whatever the country as a whole does, growth will be about 2%, plus or minus an amount too small to measure (the two digits to the right of the decimal point are only there for illustrative purposes). That has to provide some measure of assurance.