The electricity market is taking on a shape quite different from its past, with a markedly smaller role for industrial consumers. Consumption of electricity by industry declined significantly in 2015, according to US government figures, despite reasonably strong economic recovery and soft prices. Canadian figures suggest a similar long term trend.

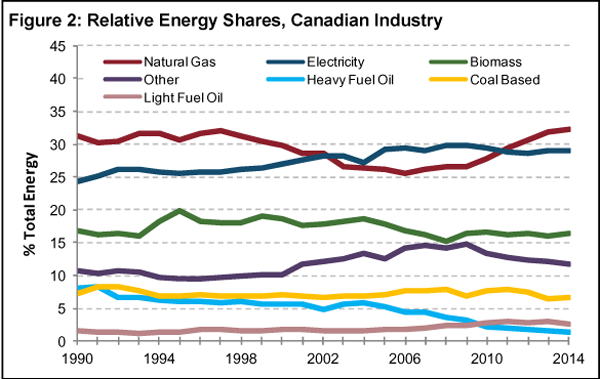

Historically, more than half of all power has been consumed by industry. Two major factors are typically associated with declining industrial power consumption, neither of which are related to any reduction of overall output from industry: energy intensity, or the amount of energy required to produce a dollar of output, has fallen over the last 20 years, and some industries have changed their fuel mix, shifting away from electricity.

Historically, more than half of all power has been consumed by industry. Two major factors are typically associated with declining industrial power consumption, neither of which are related to any reduction of overall output from industry: energy intensity, or the amount of energy required to produce a dollar of output, has fallen over the last 20 years, and some industries have changed their fuel mix, shifting away from electricity.

Total industrial consumption of electricity in the US dropped by 6.7 percent in nominal terms during the first 11 months of 2015, compared to the same period a year earlier. This dramatic change took place during a period of reasonably healthy overall economic growth, as the US had largely pulled out of its previous recession. Industry now consumes 17 percent of US electricity, a figure that would have been unimaginable a few decades ago. Consumption by commercial customers shows a similar although less pronounced decline.

Only the mighty residential consumer appears to be bravely continuing to increase its consumption of electricity, in both absolute terms and in percentage terms. This long term trend suggests that the power industry, not to mention regulators and policy makers, are likely to be increasingly focused on the needs and characteristics of residential consumers as they design policy and craft legislation. The behavior of residential consumers is very different than that of industrial consumers, and itself subject to structural change as technology for residential power consumption becomes more widely available.

Steve Mitnick, Editor-in-Chief of Public Utilities Fortnightly, recently wrote that, “Residential sales now account for 46 percent of electricity’s revenues. From the standpoint of the grid’s financial health, what happens in residential sales (and utility regulation in this area) is becoming ever more crucial.”

The broader issue is that total power sales are in decline. Although there has been growth in residential consumption it has not been sufficient to offset decline in the industrial and commercial sectors. Mitnick reported in February that, “Revenues from sales of electricity were down three billion dollars, nationally, 2015 through November, per the Energy Department. Unadjusted for inflation. That’s a decrease of nine tenths of a percent from the prior year.”

No doubt the power industry has noted these declines and made adjustments already. Quite likely those involved in financing of new generation capacity have become focused on the timelines for replacement of existing capacity, in addition to turning their eyes to markets outside of North America.

Although 2015 data is not yet available for Canada, energy use in manufacturing industries in Canada is “nearly 8% lower than what it was in 1990 and 17% lower than the 2004 peak,” according to CIEEDAC, the Canadian Industrial Energy End-use Data and Analysis Centre (CIEEDAC) at Simon Fraser University. “Yet, in spite of this increase, we see emissions levels actually declining another 1% from last year to stand 25% lower than it was in 1990. With industry GDP 3% higher than 2013, energy and GHG emissions intensities have declined.”

“This decline in energy intensity brings it to its lowest level since 1990, matching the previous low in 2006. … since 2000, intensities have actually been quite flat. It took nearly 31% less energy to generate a dollar’s worth of goods in 2014 than in 1990,” CIEEDAC reported. “Just to be clear, this is not a measure of energy efficiency in a physical sense. Value added in manufacturing industries (i.e., GDP) is not tied only to physical production of a product or service nor does it reflect very well changes in energy used in production. Further to this, shifts in industry structure where energy intense industries, like steel or cement production, diminish and less intense ones, like auto or furniture manufacturing, increase, will cause the energy intensity value to drop. Such factorization analysis was not undertaken by CIEEDAC.”

For decades electricity policy makers have often been told that the primary consideration when crafting policy should be the retention of industrial load. Now it appears that such efforts were futile, or policy makers have left such advice go largely unheeded, or both.