Is it possible that the single most effective solution to Ontario’s energy problems, and possibly Canada’s, has been staring us in the face for years, while somehow remaining seriously underused? Is it believable that there exists one silver bullet anywhere that can simultaneously reduce the need for large central agencies, improve supply, reliability, efficiency, competition, and environmental performance all at once?

The Ontario government recently announced special deals for beleaguered northern pulp and paper mills, giving many companies a rebate on their electricity prices. Fortunately, it was a targeted subsidy, the kind that does not badly affect the rest of the market. But it underlined the fact that electricity prices are heating up as an issue, and gaining increasing attention in public policy circles.

Complex systems rarely respond well to simple solutions, and electricity is no exception. But as simple solutions go, market-based pricing has few peers. That may explain why its potential is so great today. The last twenty or thirty years have seen great changes in Ontario’s approach to market pricing for electricity, but despite significant improvements, many of us remain insulated from the real cost of power.

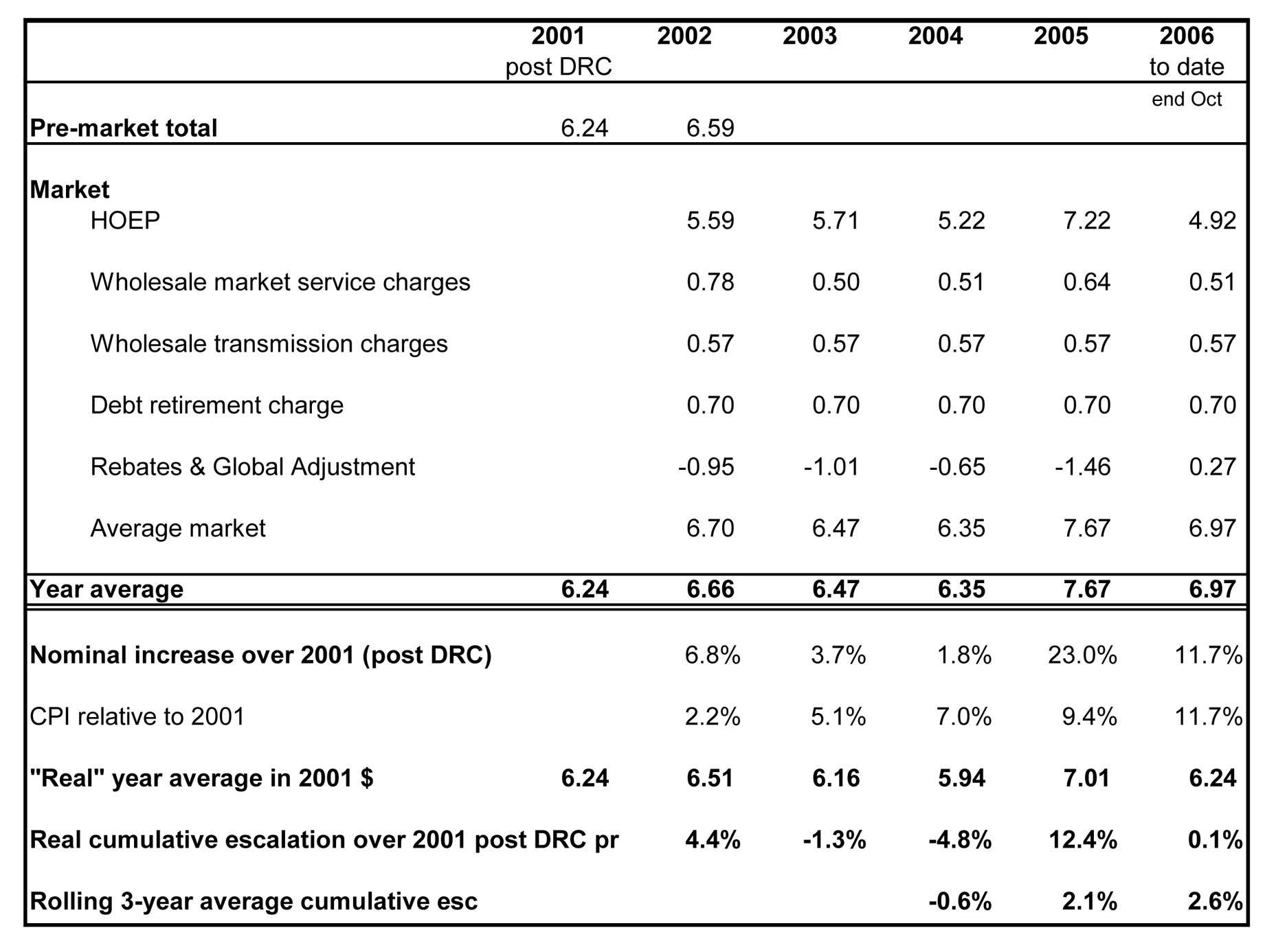

In the 1980’s, Ontario Hydro’s costs were adding up so fast that despite sizable rate increases, major debts piled up on Ontario Hydro’s books without being accounted for in prices for power. In the 1990’s under NDP and Conservative regimes, debt continued more or less unabated, while premiers created unsustainable expectations with the public by proudly promoting Ontario Hydro’s voluntary price freezes. Mike Harris bravely ended the freeze, and there was a brief period when it looked like market pricing would be allowed to operate, within a system of impartial rules and regulations. But that was before Ernie Eves returned to the old ways and instituted his government’s infamous price freeze. When Dalton McGuinty was elected in 2003, he talked earnestly about realistic pricing, and took some positive steps in that direction. But a variety of other impediments still continue to suppress and/or obfuscate prices, to the point that for a good number of consumers, real prices are no higher today than they were in 1993 or 20011. In fact, as OPG President Jim Hankinson has recently pointed out, prices continue to weaken.

Yes, that’s right: After compensating for inflation, the total cost of electricity to large industrial customers with system average load profile was practically the same for the first 10 months of 2006 as it was under Ontario Hydro’s published rates in 1993 or in 2001 before the market opened. (See the chart of historical prices on page 6.) You don’t hear that kind of message from many consumers, or even from political commentators. If anything, you hear the opposite in the media.

These relatively comforting figures are not every customer’s situation of course: A few industrial consumers in Ontario were enjoying very attractive discount rates in the 1990’s which have generally been phased out since that time. Customers connected to distribution have seen greater increases, mainly because of additional charges for debt and equity capital that are passed through by the distributors. The main point is that, although many customers have seen significant increases in the price for power, as a whole the situation is far from dire.

So while there may be specific customer circumstances that require attention, the public commentary has not always been grounded in reality. Regardless of the actual situation, fear tactics sometimes play well, and can pick up considerable media spin.

All over the world, market designers and regulators have noticed that market-based prices usually don’t reflect full costs, only variable costs, and that they therefore aren’t sufficient to attract investment in new capacity. Market prices may cover a lot of the costs of new capacity, but not quite enough, unless they are allowed to get to the point where shortages or near-shortages cause dramatic price spikes. Since that kind of volatility would be hard for most consumers to deal with, and might attract political intervention, the theory says that a capacity market is needed alongside the energy market. An ongoing competitive process can be used to secure guarantees from generators to supply the market during critical periods. The OPA’s procurement processes are in principle a substitute for a capacity market. Arguably, the system as a whole could spend less, and benefit more, by converting some of the current procurement processes into an enduring market for capacity.

Many people believe that the institution of a capacity market would allow market based pricing to work better, by correcting one of the key weaknesses in the energy-only market. Unfortunately, capacity markets are complex and aren’t likely to be implemented in the short-term. For this reason, many in the industry continue to work for the development of a capacity market, while simultaneously striving to improve the energy market.

From an objective perspective, there are reasons to think that electricity prices might have risen more, but for the new generation that is starting to come on line as a result of RES and CES contracts. The evident need for PPAs and other adequacy mechanisms demonstrate pretty conclusively that Ontario’s real-time energy market prices are below the total costs of generation, particularly the new generation investment required to meet the increasing needs of consumers. The fundamental economics of electricity production are widely understood as those of an increasingly valuable and scarce resource. Power is one of the few commodities whose production doesn’t get cheaper when consumers use more of it. The total cost of output from new generating capacity, whether it’s built to replace aging assets or to meet growth in demand, is always going to be more expensive than the generation mix we already have. All the best hydro-electric sites have been developed, materials and fuel prices aren’t going down, and society’s increasing expectations for high reliability and better environmental performance consistently add to the cost of new generation. There are some economies of scale that should reduce the cost of new generation somewhat, but they are small compared to the escalation in the cost of basic materials and feedstocks on which power plants depend. The inescapable fact is that the real cost of electricity is frequently masked by artificial distortions affecting pricing, and this creates unrealistic expectations and behaviours. The accumulated stranded debt and to some extent, the difference between forward contract prices and consumer prices, are general measures of these distortions because they represent the difference between actual costs and the amounts consumers pay.

There seems to be a double standard on pricing that runs throughout society. In principle, nearly everyone agrees that prices for power must reflect the full cost of construction, operation, fuel, and environmental protection. But in practice, hardly anyone seems prepared to take responsibility for the inevitable conclusion. Sometimes prices have to go up.

There are a number of groups in society who actually perpetuate this double standard by feeding the public with unsustainable expectations. A few industry associations, opinion leaders, policy makers, activists and consumer groups, sometimes use one-sided data and pretend that prices are already too high as a means of building political pressure on government to keep power prices artificially low. They may be doing little more than obscuring the facts and inadvertently expropriating cash from their children. Price management today only delays the time when the real costs come through, and it creates new complexity and costs to add to the burden.

There is sometimes suspicion that generators are making too much money. Many generators are indeed large companies with healthy balance sheets. But there’s one critical factor that needs to be impressed on the public. Generators have no negotiating power in the market – they are either price-takers or, like OPG, subject to regulation. Unlike consumers, they can’t move their business elsewhere if they don’t like the price. And what’s more, if generator prices start getting out of hand, there’s the constant opportunity, and the natural incentive, for other generators, consumers or anyone at all, to enter the generation business (or the efficiency business) and offer power services at a more reasonable price.

The Ontario government recently hosted a set of discussions on how to deal with the threat of climate change. It filled rooms with economists, environmentalists, industrial leaders, energy and finance experts to help develop solutions. Some good ideas came forward, if somewhat recycled: Recommitment to major progress in energy efficiency, renewables, smart regulation, fuller co-ordination between the various arms of government, targeted public education, more thorough data collection, and so on. There seemed to be a general belief however, that none of this is likely to work well unless prices are allowed to rise significantly to reflect long term costs. There you have it: Climate change, one of the most serious challenges of our generation, can not be addressed effectively at today’s energy prices. Prices may not be the only solution, but a tool kit that doesn’t include price-based incentives is not likely to work.

In truth, market based pricing, in which supply and demand are allowed to determine prices with minimal interference, is not simple or easy to implement. Like any other part of the economy it requires rules and regulations. Fortunately, the central mechanism, the wholesale power market, battered as it may be, continues to survive in Ontario. The most complex part of market-based pricing is not the pricing system, but managing the politics. The best option, much discussed and little implemented, is to go as far as possible to remove the politics from pricing. To the credit of Premier McGuinty, Energy Minister Duncan and OEB Chair Howard Wetston, the Regulated Price Plan for small consumers does go a long way to reducing the amount of politics in pricing. But there’s still a lot further to go before prices can be considered non-political.

None of this is to suggest that we should be insensitive to genuine hardship that is exacerbated by electricity prices. As countless economists have said, the proper way to protect vulnerable consumers is to use government tax and fiscal policy tools with financial aid targeted to individuals, rather than by manipulating the price of a commodity that has many more functions in the economy than supporting the necessities of human life. Ontario will be able to afford to be more generous to its needier citizens if it’s systematically minimizing inefficiency and waste with accurate electricity prices.

While Ontario has a very carefully-crafted market system for electricity with all kinds of sensible design features to its credit, it also has a raft of artificial rules and regulations that interfere with or obscure pricing signals, while providing minimal or no benefits to consumers in the end. The overall effect of the many artificial price suppressants is to oblige government and regulators to devise additional ways of bringing reliable capacity to the market, and for keeping it running. A variety of special-purpose rules and not terribly efficient regulations is the inevitable result. Some rules suppress price, while others try to counter the unintended effects of the previous rules, in an almost endless cycle. While each little rule probably has its advocates, and may seem too small to fuss over, the overall effect is significant distortion. The suppressants to price are subtle and insidious. For example:

• Import and export rules that pay Ontario generators consistently less than the full price, and less than that paid to importers, primarily because imports are over-scheduled from a cost perspective, and import and export prices are not factored into Ontario’s market clearing prices (Using the highest forecast demand in the upcoming hour when scheduling imports and exports regardless of whether there are ample domestic resources to meet reliability requirements.)

• Ramp rate rules which pretend that generators can accelerate (or ramp) 12 times faster than they can in reality – which dampens price volatility without recognizing actual ramping costs and the benefits ramp provides to loads

• Ignoring the physical restrictions of the transmission system when determining price

• A wide variety of wholesale services that consumers pay for through uplift charges, rather than being factored into energy prices

• The expectation that OPG is to collect significantly less than the standard commercial rate of return when operating its facilities

• Absence of any requirement to retire accumulated debt on a fixed schedule. Even the old Power Corporation Act set statutory requirements for retiring minimum amounts of public electricity debt every year.

If our public leaders want to really serve the public, it will be important that the full story of Ontario’s power system be told. Prices are not through the roof, and are actually relatively moderate in international terms, and historic terms. (See the article on recent pricing studies, page 25 in this issue.) Granted, Ontario is currently in a transition period, in which we are moving slowly toward a more competitive system, while retaining many of the protections of a regulated system. This may explain some of our current difficulties but it’s no excuse for complacency. At times like this it’s even more important to clarify the direction for evolution, pick up the speed and establish momentum toward the chosen goals.

Electricity prices ought to reflect the true cost/value of production. Competition is an effective means of setting appropriate prices, and is working reasonably well in Ontario at the wholesale level. Most attempts to manage the price of electricity cause problems that cost more than they save. We already have too many rules that have the effect of suppressing price, and messing up critical functions in the system. In this sense, markets with multiple sellers and buyers combined with judicious application of regulation where necessary are likely to be more efficacious at arriving at the optimal price for electricity. Efficiency, reliability and environmental performance are all tied to letting prices rise or fall to their natural levels.

In the end, what APPrO and many others are looking for is a pricing system that encourages economically rational behaviour and which recognizes that robust markets are the best way to harness the benefits of competition. There may be no silver bullet, but market based pricing is as close as we’re likely to find in the near future. It’s a story that has to be told.

*1 See the attached table, in which the calculations behind these conclusions are laid out.

This editorial was originally printed in IPPSO FACTO, December 2006.