In the midst of what is routinely being called an economic meltdown, some high-technology ventures are still managing to find early development funding, particularly those working on advanced renewable energy systems.

One such ambitious start-up is The Solar Venture, with a commercial lab operating in downtown Toronto, developing a new generation of photovoltaic cell. The company is drawing on advanced technology from a number of partner firms and working in close collaboration with research groups from the University of Toronto and the Université de Montréal.

One such ambitious start-up is The Solar Venture, with a commercial lab operating in downtown Toronto, developing a new generation of photovoltaic cell. The company is drawing on advanced technology from a number of partner firms and working in close collaboration with research groups from the University of Toronto and the Université de Montréal.

The partners describe their target as a fourth-generation, low-cost, high-efficiency, thin-film solar cell design based on “hybrid organo-metallic polymers.” It will combine the best of several worlds: an unprecedented thin film energy efficiency of 15% from cheap commercially-manufactured thin-film units, not merely laboratory models; and broad, convenient application – in effect, if not the holy grail of photovoltaic power, something approaching it.

The company’s expected breakthrough relies on several innovations: first, proprietary complex hybrid organic compounds that assemble ultra-thin layers in a high degree of order, via prolific multi-layer commercial printing processes; second, using nanotechnology components in a “stacked-cell” structure with exceptional charge transfer physics appear able to turn broad wavelength ranges into electricity relatively efficiently.

The company’s expected breakthrough relies on several innovations: first, proprietary complex hybrid organic compounds that assemble ultra-thin layers in a high degree of order, via prolific multi-layer commercial printing processes; second, using nanotechnology components in a “stacked-cell” structure with exceptional charge transfer physics appear able to turn broad wavelength ranges into electricity relatively efficiently.

In technospeak, “charge transfer physics” is the means used to get the electrons flowing directionally out of the layers and into the wires with minimal loss of energy. For organic solar thin film devices this is a serious challenge that has so far prevented any of them from approaching their theoretical potential.

In technospeak, “charge transfer physics” is the means used to get the electrons flowing directionally out of the layers and into the wires with minimal loss of energy. For organic solar thin film devices this is a serious challenge that has so far prevented any of them from approaching their theoretical potential.

The third major innovation, the icing on the cake, will be a commercial scale, open-air manufacturing facility costing a small fraction of the hundreds of millions of dollars of capital needed for silicon cell manufacturing plants.

The company is nothing if not ambitious. Still at the stage of securing patents, it expects to be in commercial manufacture in four to five years.

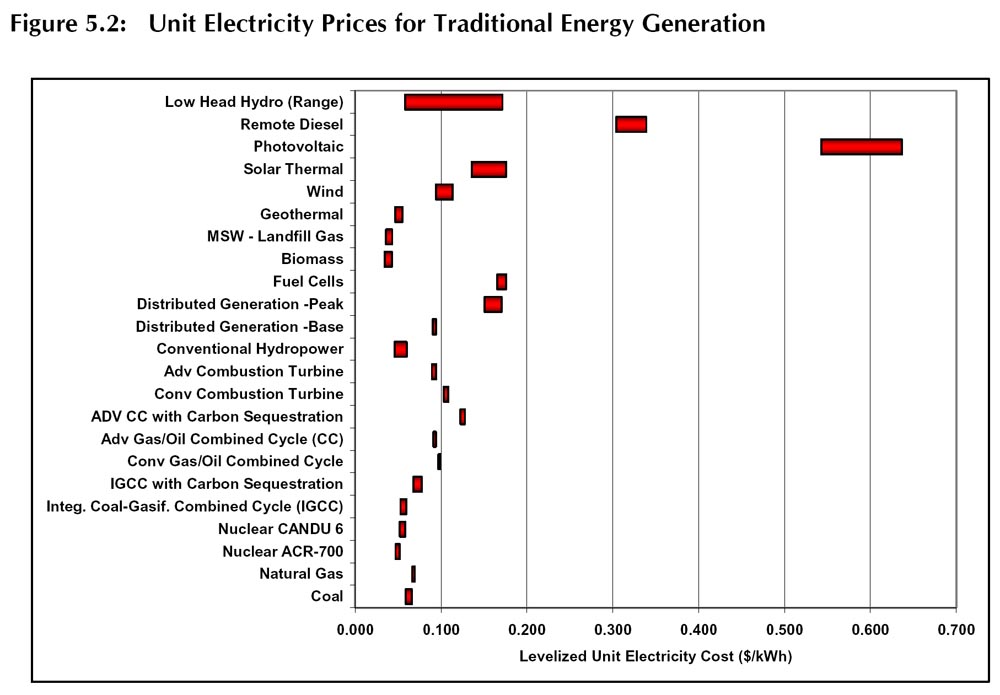

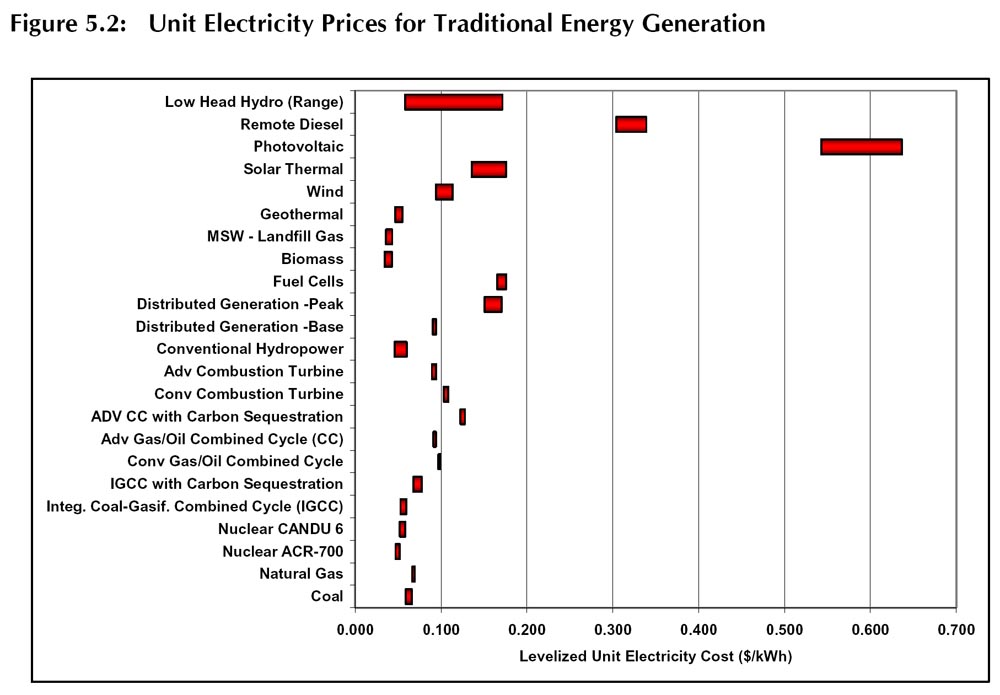

“It’s still early days in solar,” said Business Development Vice-President Karen Grant in a telephone interview. “Thin film solar technologies had no commercial market share in 2005, but are projected to represent almost 33% of the market by 2012. They are a third to half of the cost of silicon to manufacture, and are easier to work with. Our technology is intended to further boost thin film efficiency and to further lower its end cost.”

The company has so far secured $4.25 million in capital: $1 million from four angel investors (including Burlington, Ontario-based Trivaris), $1.5 million from the Ontario Centres of Excellence (OCE), $250,000 from the Ontario Power Authority (funding managed by the OCE), and $1.5 million from GrowthWorks Capital.

Other promising technologies that have recently received funding from the Ontario Power Authority include a very low head (VLH) hydroelectric turbine and an Energy Hub Management System. The VLH turbine initiative received initial funding as well from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan).

The VLH hydro turbine, being developed in a joint effort through a Canada-France partnership, can take advantage of sites with a drop of just one to three metres. Rather than relying on large and expensive civil-engineering structures, as conventional hydro projects do to maximize the energy delivered to a mechanically compact turbine, the innovation in this case is to make the intake structure cheap and simple and to make the turbine runner large instead. The energy of water falling a short distance is in this case captured by large, slow-turning blades in a simple frame, set inside an inexpensive diversion channel next to a dam or weir. Cynthia Handler, Senior Renewable Energy Engineer at NRCan, which provided research and development funding, explains that while several designs exist for low-head turbines, no other uses this concept.

An advanced low-speed generator is connected directly to the runner shaft. The turbine is lowered into the water from above, and can be raised for maintenance. Hydraulic efficiency is expected to run around 90%, and total system efficiency at 76%.

The prototype, developed with a French partner by Turbines Novatech-Lowatt Inc. in Beloeil, Quebec, has been undergoing testing since early 2007 at a site in Millau in the south of France. The next step will be testing of a demonstration plant at a site in Canada, and several companies are in the permitting stages. The proponents have studied the economics using NRCan’s RETScreen project analysis software, and the results are favourable, relying on the OPA’s 11 cents per kWh under RESOP. NRCan is hoping to have an installation at some location in early 2010.

The technology is particularly attractive because the typical installation will be at a site that already has some kind of civil structure on it – a water level control weir, or something of the sort – which means it will be close to population centres, and likely requires lower cost for connecting to the grid. One demonstration site being looked at is right next to a hydro pole, Handler says.

Hatch Energy has prepared a low-head market assessment report, which includes a review of past hydropower studies and databases that turned up over 2300 small (under 50 MW), low-head hydropower sites with a combined potential capacity of almost 5000 MW across Canada. In Ontario and Manitoba, it found 21 low-head sites with individual capacities of more than 50 MW amounting to a combined capacity of more than 3000 MW. Measured differently, in Ontario at less than 15 metres of head, NRCan is aware of potentially 2000 MW worth of low-head hydro sites, of which 573 MW is expected to be economic.

The Energy Hub Management System being developed out of the University of Waterloo to allow real-time management of a location’s energy demand, production, storage and resulting import or export of energy. A central core at the location will collect information from two-way sensor controls placed on energy-consuming devices, as well as information from the external environment (for example, local electricity conditions, electricity market prices and weather forecasts), and will make decisions in order to manage energy effectively. A third component, a web-based portal, plus state-of-the-art wireless communication devices, will allow the system’s managers to optimize both energy consumption and energy production – such as embedded cogeneration – locally or remotely.

Project documentation explains that pilot projects will be set up in different locations. Each location would potentially be an energy producer (for instance, have a combined heat and power unit), an energy consumer (electric motors, for example), an energy importer (natural gas requirements for its boilers), an energy exporter (electricity at peak price periods) and an energy storer (battery bank).

Project leader Professor Ian Rowlands at the University of Waterloo’s Faculty of Environment explains that while the system is ideally designed to operate in an environment with all these aspects (energy production, energy consumption, energy storage, energy import and export), it can also find employment in locations, particularly pilot implementations, that lack one or more of those, depending on what’s available.

Technology will be developed that will integrate these systems, developing models and decision rules to determine whether the combined heat and power unit should be operated, or whether energy should instead be imported, to determine whether excess energy should be sourced (through generation and/or import) and stored in order to be used later, and to determine whether manufacturing operations should be curtailed in order to take advantage of demand response programs being offered (for example, interruptible load tariffs). To do this effectively, the hub’s control technologies will be embedded within the ‘bigger picture’ (markets and grids) and will also be reactive to the demands of the individuals (workers and immediate neighbours) who work and/or live within the hub. Development involves both specialized hardware for the hub, plus the software to run the system. It will be able to communicate with the various devices already available on the market to control individual pieces of equipment.

Initial funding for the project was provided by the OCE, in addition to $250,000 from the OPA that is being managed by the OCE. Several other partners – Hydro One, Milton Hydro and Energent – are also providing a mix of funding and other resources.

All three of the above projects have received $250,000 in funding from the OPA. , managed through the OCE. The Solar Venture and Energy Hub projects are managed by the OCE and the VLH project is managed by CEATI International.